by Mindy Clegg

Rarely do presidential elections seem so consequential, but 2020 has us all in agreement that voting is critical this year. Many simply yearn for a return to “the normal” of the Obama era or the Clinton years. Is the normal of the 90s and 2000s far enough to really address our various existential crises? I argue no. It’s clear that whatever our political orientation, we’re all reeling from the ongoing pandemic (and the threat of more in the future), global economic precarity (from several decades of neo-liberal policies, exacerbated by the pandemic), the erosion of individual rights among those historically oppressed, the rise of the hard right and the terroristic threats they pose, some left-wing accelerationism on the left, as well as the looming existential crisis of climate change, among other things. A general consensus has emerged that the current administration made these issues worse.

With the exception of a few hardcore holdouts, many prominent members of the President’s own party have come to admit the administration’s failures to address the above issues. Yet the administration represents the logical conclusion of the rightward lurch of the Overton window advocated by the GOP for years now. A quick survey of American and global politics tell us that the post Cold War neoliberal solutions failed us all. As we stare into the void that is 2020, now seems the perfect time to reassess and reorient ourselves to push for a more productive mode of problem-solving from our governments. Although voting Democratic down your tickets could begin this process, a real shift to creating more responsive governance that puts citizens first for the country and world will need active engagement and large-scale collective problem solving based on scientific facts rather than ideology. It is helpful to know the roots of our current problem so I will focus on two byproducts of the Cold War itself: the rise of neoliberal economic structures and the culture wars, and how Republicans and Democrats reacted to both. Solving these problems will require a strong political will for a New Deal level intervention that both regulates the economy and offers protection of basic rights for all. Read more »

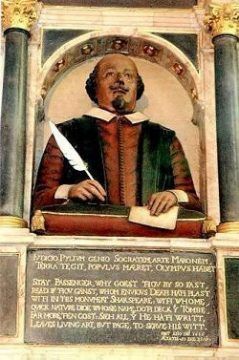

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

![Shakespeare & Company, Paris. [Wikipedia]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SandC.jpg)

Founding editor of The Baffler and author of prophetic classics like Listen, Liberal and What’s the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank skewers received wisdom across the political spectrum. In his new book, The People, No, Frank reveals that the Democratic Party has tied itself in knots about a phantom of its own making: populism. The original Populists—19th-century agitators for working people’s interests—spawned a revolving cast of journalists, intellectuals, and business interests determined to paint them as villainous xenophobic masses. These anti-populists have made the name of the movement into a dirty word. Today’s anti-populists equate the broad multiracial coalition of social-justice activists that supported Bernie Sanders with a very different alliance that championed Donald Trump in 2016.

Founding editor of The Baffler and author of prophetic classics like Listen, Liberal and What’s the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank skewers received wisdom across the political spectrum. In his new book, The People, No, Frank reveals that the Democratic Party has tied itself in knots about a phantom of its own making: populism. The original Populists—19th-century agitators for working people’s interests—spawned a revolving cast of journalists, intellectuals, and business interests determined to paint them as villainous xenophobic masses. These anti-populists have made the name of the movement into a dirty word. Today’s anti-populists equate the broad multiracial coalition of social-justice activists that supported Bernie Sanders with a very different alliance that championed Donald Trump in 2016. It is hard to imagine more devastating effects of climate change than the

It is hard to imagine more devastating effects of climate change than the  You will surely

You will surely  Spoon-benders are unlikely to be the only profession toasting the disappearance – supposing we rule out further hauntings – of Randi, who, being himself a brilliant magician as “The Amazing Randi: The Man No Jail Can Hold” (previously “The Great Randall: Telepath”) was repeatedly more effective than scientists at examining paranormalist claims, sometimes by simply performing their stunts himself.

Spoon-benders are unlikely to be the only profession toasting the disappearance – supposing we rule out further hauntings – of Randi, who, being himself a brilliant magician as “The Amazing Randi: The Man No Jail Can Hold” (previously “The Great Randall: Telepath”) was repeatedly more effective than scientists at examining paranormalist claims, sometimes by simply performing their stunts himself. Weathered, wiry and in his early 60s, the man stumbled into clinic, trailing cigarette smoke and clutching his chest. Over the previous week, he had had fleeting episodes of chest pressure but stayed away from the hospital. “I didn’t want to get the coronavirus,” he gasped as the nurses unbuttoned his shirt to get an EKG. Only when his pain had become relentless did he feel he had no choice but to come in. In pre-pandemic times, patients like him were routine at my Boston-area hospital; we saw them almost every day. But for much of the spring and summer, the halls and parking lots were eerily empty. I wondered if people were staying home and getting sicker, and I imagined that in a few months’ time these patients, once they became too ill to manage on their own, might flood the emergency rooms, wards and I.C.U.s, in a non-Covid wave. But more than seven months into the pandemic, there are still no lines of patients in the halls. While my colleagues and I are busier than we were in March, there has been no pent-up overflow of people with crushing chest pain, debilitating shortness of breath or fevers and wet, rattling coughs. But surprisingly, even months later, as coronavirus infection rates began falling and hospitals were again offering elective surgery and in-person visits to doctor’s offices, hospital admissions remained almost 20 percent lower than normal.

Weathered, wiry and in his early 60s, the man stumbled into clinic, trailing cigarette smoke and clutching his chest. Over the previous week, he had had fleeting episodes of chest pressure but stayed away from the hospital. “I didn’t want to get the coronavirus,” he gasped as the nurses unbuttoned his shirt to get an EKG. Only when his pain had become relentless did he feel he had no choice but to come in. In pre-pandemic times, patients like him were routine at my Boston-area hospital; we saw them almost every day. But for much of the spring and summer, the halls and parking lots were eerily empty. I wondered if people were staying home and getting sicker, and I imagined that in a few months’ time these patients, once they became too ill to manage on their own, might flood the emergency rooms, wards and I.C.U.s, in a non-Covid wave. But more than seven months into the pandemic, there are still no lines of patients in the halls. While my colleagues and I are busier than we were in March, there has been no pent-up overflow of people with crushing chest pain, debilitating shortness of breath or fevers and wet, rattling coughs. But surprisingly, even months later, as coronavirus infection rates began falling and hospitals were again offering elective surgery and in-person visits to doctor’s offices, hospital admissions remained almost 20 percent lower than normal. What’s it like to be a cat?

What’s it like to be a cat?  Timothy Larsen over at the LARB:

Timothy Larsen over at the LARB: Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum:

Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum: