by Ali Minai

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna see,

I guess an’ fear!

—Robert Burns, “To a Mouse”

On January 24, 2017 – four days after Donald Trump was sworn in as the 45th President of the United States – I sat down at my computer and wrote out an 8-point plan by which I feared he and his party could change forever the nature of American democracy. Now, as we approach another presidential election, it is interesting to look back and take stock.

Here was the plan – reproduced verbatim without any change except a small typo correction:

Step 1: Delegitimize all authoritative sources of information – mainstream media, scientists, economists, historians, other experts.

Step 2: Use control of government resources to foment conspiracy theories and generate fake information (including fake data) to delegitimize popular predecessor.

Step 3. Use the judiciary and the legislature to criminalize criticism and dissent.

Step 4 Stop keeping track of data that would quantify inconvenient facts about climate change, economic inequality, social problems, civil rights problems, gun violence, police brutality, corporate greed, foreign wars, etc.

Step 5: Use control of government institutions to revise previous data and generate new false data to shape perceptions of prior dysfunction and current progress.

Step 6: Divide the opposition by tangling them in internal feuds on issues such as trade, race, political correctness, Israel, etc.

Step 7: Pack the bureaucracy and judiciary as far as possible with compliant functionaries who support the program.

Step 8: Use government institutions to ensure single-party electoral dominance for the foreseeable future, thus removing all fear of public accountability.

I would now like to pose two questions:

- Was all this possible in January 2017?

- Did it come to pass, and if not, why not?

To answer the first question, yes, it was certainly possible. The mechanisms were all there. Trump had come in with Republican majorities in both houses of Congress. The party dominated governorships and state legislatures across the country. The judiciary had already been packed well by previous Republican administrations, and the reversal of this packing stymied by Republican obstruction during the Obama years. The Right-Wing propaganda machine, led by Fox News and Talk Radio, was humming on all cylinders. Read more »

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home.

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home. Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion.

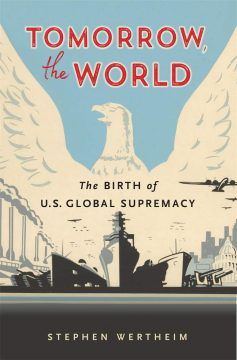

Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion. Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the

Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the  By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner.

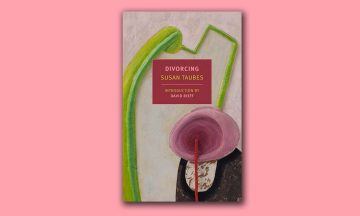

By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner. Susan Taubes’s fiction is animated by an unbearable awareness of death. Her first and only novel, Divorcing (1969), had the working title To America and Back in a Coffin. (An apt title, but deemed unmarketable and rejected by her publishers.) Like her contemporary Ingeborg Bachmann, Taubes’s fiction transposes existential mysteries with aesthetic ones. (There are other similarities between the pair: both published only one novel; both novels feature a love interest named Ivan; neither writer would live to see fifty.) Long out of print, Divorcing will finally be reissued by NYRB Classics this month. Taubes’s foreshortened oeuvre—this novel, an unpublished novella, a handful of stories—offers a range of formal precarities that mirror states of inward collapse. Fiction seemed to give shape to her own vulnerability. A lifelong depressive, she took her own life mere weeks after Divorcing was published. Her close friend Susan Sontag later suggested it was Hugh Kenner’s New York Times review that finally pushed Taubes over the edge. “Lady novelists have always claimed the privilege of transcending mere plausibilities,” he’d written. Sontag herself would identify the body.

Susan Taubes’s fiction is animated by an unbearable awareness of death. Her first and only novel, Divorcing (1969), had the working title To America and Back in a Coffin. (An apt title, but deemed unmarketable and rejected by her publishers.) Like her contemporary Ingeborg Bachmann, Taubes’s fiction transposes existential mysteries with aesthetic ones. (There are other similarities between the pair: both published only one novel; both novels feature a love interest named Ivan; neither writer would live to see fifty.) Long out of print, Divorcing will finally be reissued by NYRB Classics this month. Taubes’s foreshortened oeuvre—this novel, an unpublished novella, a handful of stories—offers a range of formal precarities that mirror states of inward collapse. Fiction seemed to give shape to her own vulnerability. A lifelong depressive, she took her own life mere weeks after Divorcing was published. Her close friend Susan Sontag later suggested it was Hugh Kenner’s New York Times review that finally pushed Taubes over the edge. “Lady novelists have always claimed the privilege of transcending mere plausibilities,” he’d written. Sontag herself would identify the body. In this didactic cultural moment, when many judge works of art by whether they deliver the right message with perfect clarity, it can be easy to forget that the purpose of novels is not to teach us life lessons or instill in us the proper view on some issue. In other words, the novel isn’t a tool of moral instruction. Rather, it’s a way to imagine how morality plays out in life, to experience vicariously how human beings—flawed, mercurial, riddled with contradictions they often don’t perceive themselves—try and fail not only to do the right thing, but even to understand what the right thing is in the first place. Sometimes that gap between our aspirations or self-knowledge and our actions can be tragic, but just as often, depending on your perspective, it can be funny.

In this didactic cultural moment, when many judge works of art by whether they deliver the right message with perfect clarity, it can be easy to forget that the purpose of novels is not to teach us life lessons or instill in us the proper view on some issue. In other words, the novel isn’t a tool of moral instruction. Rather, it’s a way to imagine how morality plays out in life, to experience vicariously how human beings—flawed, mercurial, riddled with contradictions they often don’t perceive themselves—try and fail not only to do the right thing, but even to understand what the right thing is in the first place. Sometimes that gap between our aspirations or self-knowledge and our actions can be tragic, but just as often, depending on your perspective, it can be funny. Christof Koch is a neuroscientist distinguished by his rock-solid scientific work and

Christof Koch is a neuroscientist distinguished by his rock-solid scientific work and  Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by  But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

Bill: Can you believe these Republicans?! Just four years after swearing up and down that no nominee for the Supreme Court should ever be approved in an election year for the president, and promising on their mothers’ graves that they would never do such a thing, here they are doing exactly that!

Bill: Can you believe these Republicans?! Just four years after swearing up and down that no nominee for the Supreme Court should ever be approved in an election year for the president, and promising on their mothers’ graves that they would never do such a thing, here they are doing exactly that!

Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Autumn is brilliant. One of the things I looked forward to when I moved to the Midwest from the desert southwest was the experience of a year with four seasons. I did not anticipate how very beautiful autumn could be, and even after 40 years in the Midwest, I can’t get enough of this season. I can’t spend enough time outside in the wonderfully crisp air, under the low-angle sunlight, stopping to drink in the deep burnished golds, the lemony yellows, the gloriously variegated reds and oranges.

Autumn is brilliant. One of the things I looked forward to when I moved to the Midwest from the desert southwest was the experience of a year with four seasons. I did not anticipate how very beautiful autumn could be, and even after 40 years in the Midwest, I can’t get enough of this season. I can’t spend enough time outside in the wonderfully crisp air, under the low-angle sunlight, stopping to drink in the deep burnished golds, the lemony yellows, the gloriously variegated reds and oranges.