Susan Faludi in The New York Times:

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,” Mr. Gutfeld said. “He was going to walk out there on that battlefield with you.” Senator Kelly Loeffler of Georgia tweeted an altered WrestleMania video in which the president was portrayed as pummeling senseless an opponent with a spiked coronavirus head. “President Trump won’t have to recover from Covid,” Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida gloated. “Covid will have to recover from President Trump.”

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,” Mr. Gutfeld said. “He was going to walk out there on that battlefield with you.” Senator Kelly Loeffler of Georgia tweeted an altered WrestleMania video in which the president was portrayed as pummeling senseless an opponent with a spiked coronavirus head. “President Trump won’t have to recover from Covid,” Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida gloated. “Covid will have to recover from President Trump.”

Meanwhile, the putatively liberal news media was conjuring its own version of the boxing ring: with Mr. Trump in one corner as atavistic chest-beater and Joe Biden in the other as evolved exemplar of feminist-sensitized manhood. Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden “evoke different brands of manliness,” a Washington Post article argued: Mr. Trump channels “old-fashioned machismo” — “aggressive, physically tough, physically strong, never back down” (in the words of a gender-equity educator, Jackson Katz) — while Mr. Biden models what Mr. Katz calls “a more complex 21st-century version of masculinity,” defined by “compassion and empathy and care and a personal narrative of loss.”

But what if the one thing people agree on, they’re wrong about? What if Mr. Trump’s style of bullying and bombast aren’t relics of the old manhood, but emblems of a masculinity very much au courant? If that’s so, we may be fooling ourselves in declaring that his noxious model is heading for a natural extinction.

More here.

American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”)

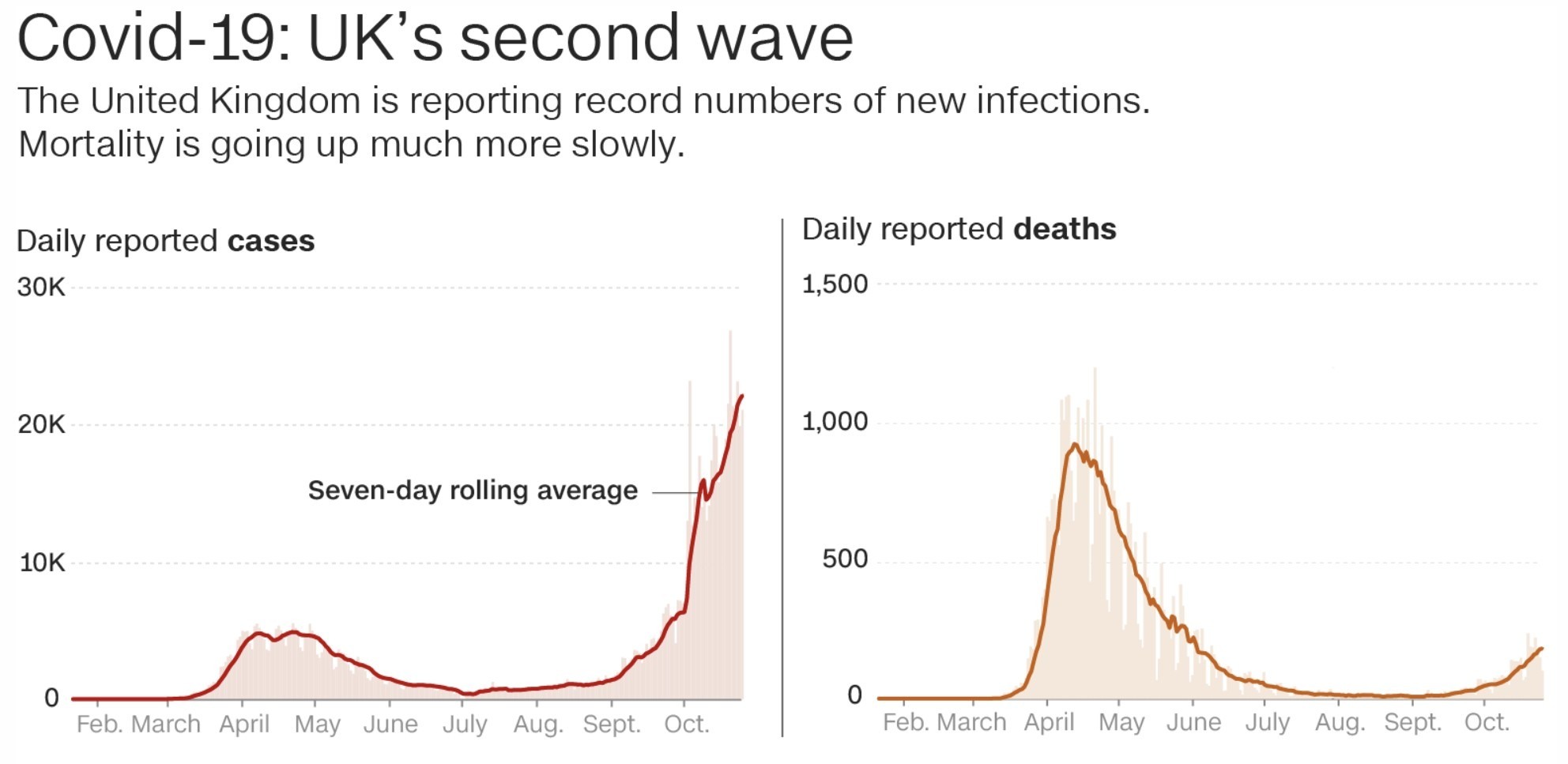

American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”) Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

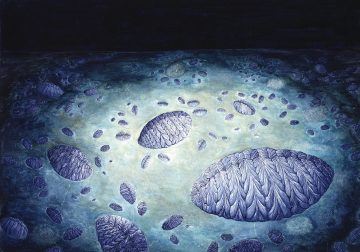

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions.

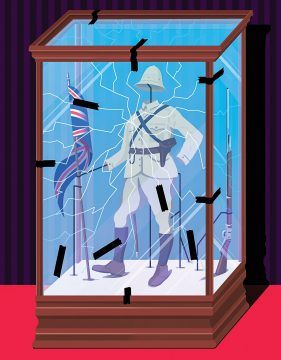

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions. On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water.

On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water. And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure. On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in

On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in  Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.”

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.” In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test  Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness.

Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness. In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how

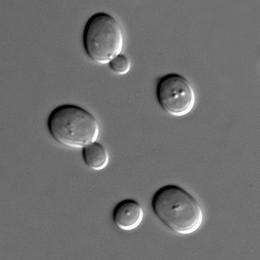

In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how  In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.

In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.