I keep lighting candles on my stoop and watching the wind snuff them out

I keep thinking about Breonna Taylor asleep/ between fresh sheets/ I keep thinking/ about her skin cooling after a shower/ about her hair wrapped in a satin bonnet/ I think about what she may have dreamed that night/ keep thinking about her bedroom/ whether she had painted it recently/ argued with her partner about the undertones in that paint/ this one more blue/ this one more pink/ that she may have felt more at home now that she had chosen the color on her walls/ I keep thinking about how she could use her hands to keep blood moving through a human heart/ how she could use her hands to stanch the flow of blood until platelets arrived/ I wonder how many times she heard/ thank you for saving/ please save/ I wonder how many nights she could/ I keep thinking about her when I lie in bed at night/ when I wake up and look in the mirror/ when I walk to my front door/ I keep thinking about the life she wanted to build/ whether she had her eye on a ring and was dropping hints to the man who chose to protect her/ whether he was working on it/ whether it was in his sock drawer already as he waited for the right time/ I keep wondering why a black woman’s death alone can’t begin the revolution/ whether the sweet smoke rising to the heavens across this nation is offering enough/

by Amy M. Alvarez

from Split This Rock

Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities. The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment.

Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities. The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment. How our experience in the theatre during one of his plays relates to our lives outside is a question that has nagged at discussions of Stoppard’s standing as a writer. His kind of quantum dramatics messes with our minds and our understanding of time and we love it, but when we get home we still have to set the alarm for work the next day. Does this mean that his plays are little more than a diverting display of verbal fireworks, clever but of no significance, or are deeper themes about our experience of life being addressed? At the very least, his work reveals a constant endeavour to decipher the puzzles of existence. As Hannah, a character in one of his best-loved plays,

How our experience in the theatre during one of his plays relates to our lives outside is a question that has nagged at discussions of Stoppard’s standing as a writer. His kind of quantum dramatics messes with our minds and our understanding of time and we love it, but when we get home we still have to set the alarm for work the next day. Does this mean that his plays are little more than a diverting display of verbal fireworks, clever but of no significance, or are deeper themes about our experience of life being addressed? At the very least, his work reveals a constant endeavour to decipher the puzzles of existence. As Hannah, a character in one of his best-loved plays,  Thirty years ago, the philosopher Judith Butler*, now 64, published a book that revolutionised popular attitudes on gender.

Thirty years ago, the philosopher Judith Butler*, now 64, published a book that revolutionised popular attitudes on gender.  In 1938, Alma Fielding, a 34-year-old housewife from the south London suburb of Thornton Heath, apparently became possessed by a violent spirit. It started one evening when Alma was in bed afflicted by kidney pain while her builder husband, Les, was suffering from tooth problems next to her. After seeing a six-finger handprint appear on the mirror, the couple were attacked by a flying eiderdown, felt a dank wind blowing and saw a glass spontaneously shatter. In the weeks and months that followed, the Fieldings, their teenage son, Don, and their lodger, George, were terrorised by what seemed wildly malevolent paranormal forces. Sunday Pictorial reporters sent to investigate were met with flying eggs, teacups breaking in midair and a brass fender thumping down a staircase.

In 1938, Alma Fielding, a 34-year-old housewife from the south London suburb of Thornton Heath, apparently became possessed by a violent spirit. It started one evening when Alma was in bed afflicted by kidney pain while her builder husband, Les, was suffering from tooth problems next to her. After seeing a six-finger handprint appear on the mirror, the couple were attacked by a flying eiderdown, felt a dank wind blowing and saw a glass spontaneously shatter. In the weeks and months that followed, the Fieldings, their teenage son, Don, and their lodger, George, were terrorised by what seemed wildly malevolent paranormal forces. Sunday Pictorial reporters sent to investigate were met with flying eggs, teacups breaking in midair and a brass fender thumping down a staircase. Jackson T. Reinhardt in Inquiries Journal:

Jackson T. Reinhardt in Inquiries Journal:

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas:

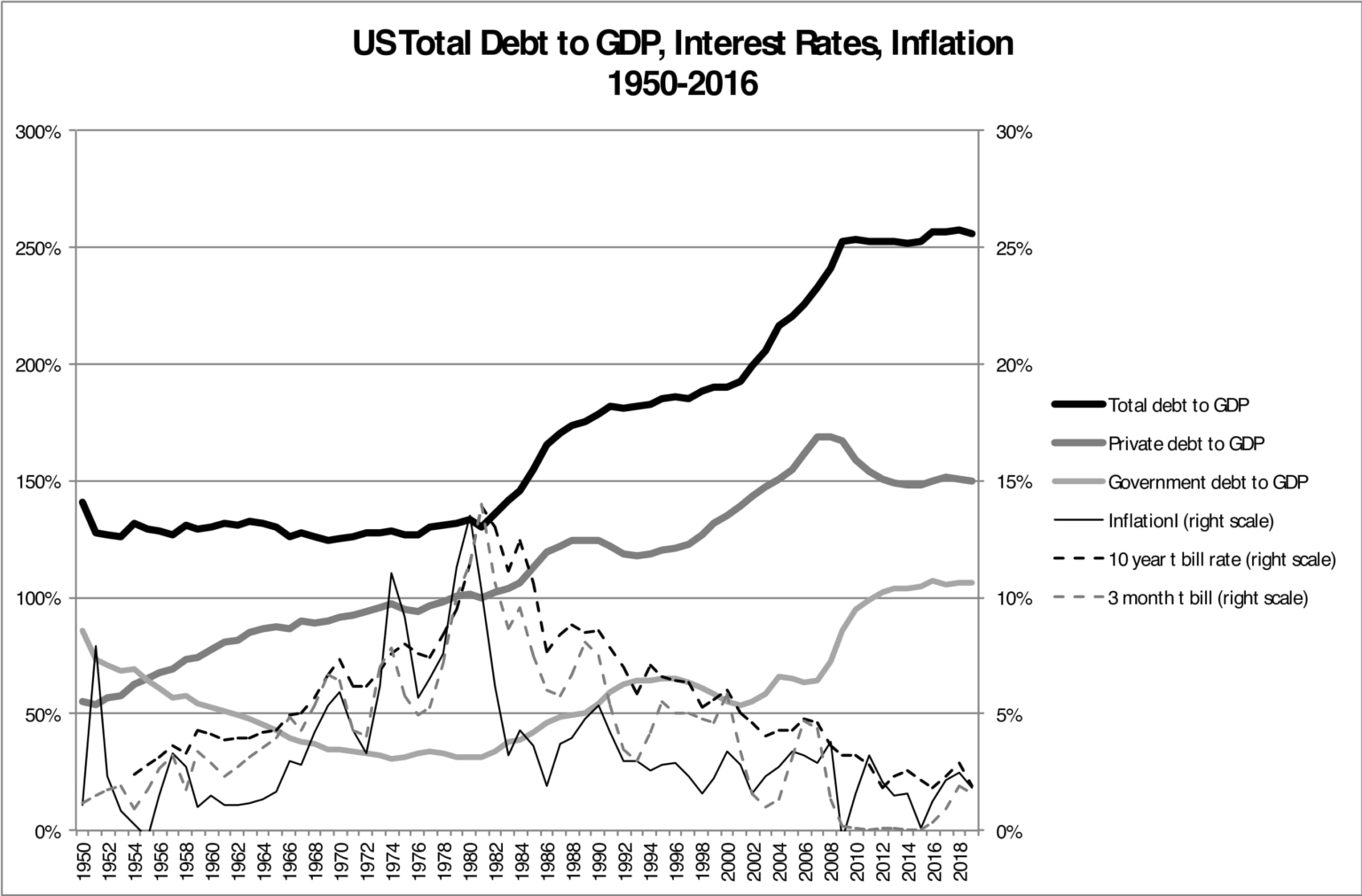

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas: Branko Milanovic in Global Policy:

Branko Milanovic in Global Policy: A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms?

A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms? Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),

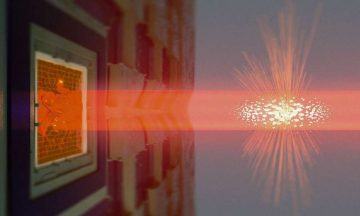

Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),  A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

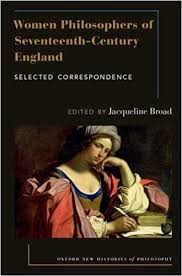

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).