by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

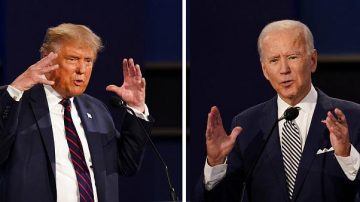

The first of the US Presidential debates between incumbent Donald Trump and challenger Joe Biden is complete, and from the looks of the political landscape after Trump’s positive COVID test, it may be the only debate for this election cycle. Most who watched the debate called it a ‘food fight,’ a ‘brawl,’ or worse. Trump interrupted Biden, there was too much crosstalk, there were insults, and Biden even told the President to “Shut up, man!” Anyone who tuned in to see two candidates for America’s highest office exchange well-reasoned arguments, hold each other accountable to challenge, and answer each other’s questions was sorely disappointed.

But the reality is that debates never have been that idealized exchange. For sure, many debates have better resembled it than this more recent one, but no debates have been close to that aspirational posit. Rather, the debates are more simultaneous campaign events, where the candidates can recite clips of their stump speeches, drop practiced one-liners, and play at having rapport with the moderator when being held to the rules of the debate. What makes them important in this argumentative regard, then, is how well they enact their brand within the rules of the forum. It’s along these lines that we think that Trump is right that he won the debate.

Biden’s brand is that he is the moderate who can beat Trump. Trump’s brand is that he is the powerful disruptor, the one who is so strong that no rules can constrain him. Seen from this perspective, the debate was wholly a case of Trump’s singular dominance. He, again, interrupted Biden, he derailed Biden’s argument about his disparagement of the military with a shot about Biden’s younger son, he squabbled with the moderator about whether the rules were right, and he consistently went over his allotted times. He indeed was a disruptor, one to whom the rules do not apply. He was consistently and manifestly on-brand. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Lesser Weaver Nests, Akagera National Park, Rwanda. 2018.

Sughra Raza. Lesser Weaver Nests, Akagera National Park, Rwanda. 2018.

Donald Trump’s presidency has generated a greater than normal interest in American politics, but not necessarily for the right reasons. How, people wondered, could such a poorly qualified candidate, and, as we have seen over the years, of equally poor calibre possibly become the President of the United States and leader of the ‘free’ world?

Donald Trump’s presidency has generated a greater than normal interest in American politics, but not necessarily for the right reasons. How, people wondered, could such a poorly qualified candidate, and, as we have seen over the years, of equally poor calibre possibly become the President of the United States and leader of the ‘free’ world?

Irish-Canadian author

Irish-Canadian author

The older man coupled with the younger woman is Hollywood tradition, from a young Audrey Hepburn pursued by Cary Grant (Charade), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), or Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina) (all of the men looking overripe and easily bruised at the time of filming), to Catherine Zeta-Jones writhing in front of Sean Connery in Entrapment, or marrying her real life partner Michael Douglas, twenty-five years her elder. This age gap coupling is also a reality; around 30 percent of American heterosexual marriages consist of men at least four years older than their partners.

The older man coupled with the younger woman is Hollywood tradition, from a young Audrey Hepburn pursued by Cary Grant (Charade), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), or Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina) (all of the men looking overripe and easily bruised at the time of filming), to Catherine Zeta-Jones writhing in front of Sean Connery in Entrapment, or marrying her real life partner Michael Douglas, twenty-five years her elder. This age gap coupling is also a reality; around 30 percent of American heterosexual marriages consist of men at least four years older than their partners. Riding through the northern Chilean Andes, an incredibly rugged swath of desert that I’m sure in times gone by has tried men’s souls —- no one would ever suspect they were about to enter a prime ground-based window onto the Universe. It’s hardly the kind of landscape that evokes oohs and aahs for its beauty. But this dust-ridden land is home to some of the world’s greatest observatories. And by night, it offers an aperture onto the center of our own Milky Way and far-flung galaxies that literally stretch back to the beginning of time.

Riding through the northern Chilean Andes, an incredibly rugged swath of desert that I’m sure in times gone by has tried men’s souls —- no one would ever suspect they were about to enter a prime ground-based window onto the Universe. It’s hardly the kind of landscape that evokes oohs and aahs for its beauty. But this dust-ridden land is home to some of the world’s greatest observatories. And by night, it offers an aperture onto the center of our own Milky Way and far-flung galaxies that literally stretch back to the beginning of time. If Joe Biden wins the White House, and Democrats take back the Senate, there is one decision that will loom over every other. It is a question that dominated no debates and received only glancing discussion across the campaign, and yet it is the master choice that will either unlock their agenda or ensure they fail to deliver on their promises.

If Joe Biden wins the White House, and Democrats take back the Senate, there is one decision that will loom over every other. It is a question that dominated no debates and received only glancing discussion across the campaign, and yet it is the master choice that will either unlock their agenda or ensure they fail to deliver on their promises. India’s golden age as the centre of the Indophilic Sanskrit cosmopolis lasted an entire millennium. From 1200 onwards, however, it was India’s fate to be drawn into a second transregional world. The first Islamic conquests of India happened in the 11th century, with the capture of Lahore in 1021. Persianised Turks, from what is now central Afghanistan, seized Delhi from its Hindu rulers in 1192. By 1323, they had established a sultanate as far south as Madurai, towards the tip of the peninsula, and other sultanates were founded all the way from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east.

India’s golden age as the centre of the Indophilic Sanskrit cosmopolis lasted an entire millennium. From 1200 onwards, however, it was India’s fate to be drawn into a second transregional world. The first Islamic conquests of India happened in the 11th century, with the capture of Lahore in 1021. Persianised Turks, from what is now central Afghanistan, seized Delhi from its Hindu rulers in 1192. By 1323, they had established a sultanate as far south as Madurai, towards the tip of the peninsula, and other sultanates were founded all the way from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east. The world might be a different place if American Presidents had not been felled by disease or hidden debilitating conditions. In February, 1945, just two months before his death, President

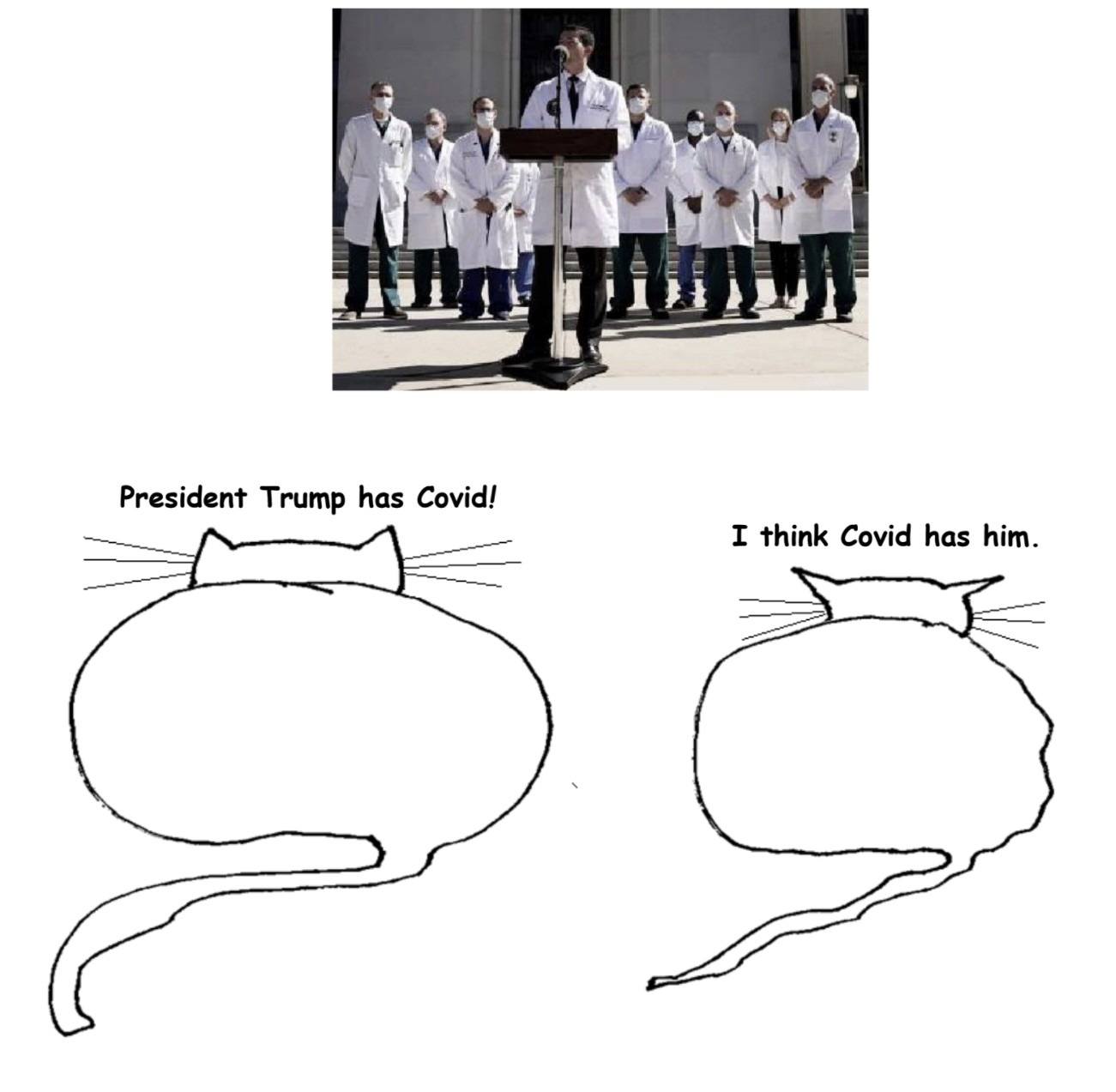

The world might be a different place if American Presidents had not been felled by disease or hidden debilitating conditions. In February, 1945, just two months before his death, President