Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog:

Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog:

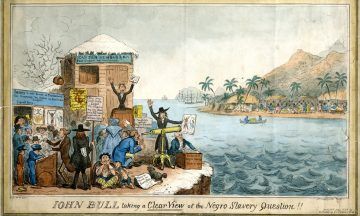

In recent weeks, President Trump has spent a great deal of time articulating a specific and extreme vision of American patriotism. This vision asks us to remember and celebrate only the most idealized American histories and stories, and defines any deviation from those celebrations as nothing less than unpatriotic hate.

Trump expressed this absolute form of patriotism in the September 17th speech announcing his “Patriotic Education” Commission, calling the New York Times’ 1619 Project “a crusade against American history,” “toxic propaganda,” and “a form of child abuse.” He claimed that “patriotic moms and dads are going to demand that their children are no longer fed hateful lies about this country.” And he did so again in his recent Columbus Day proclamation, arguing that the “extremists” who would “replace discussion of [Columbus’] vast contributions with talk of failings … seek to revise [history], deprive it of any splendor, and mark it as inherently sinister,” and that in response “we must teach future generations about our storied heritage.”

More here.

Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review:

Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review: Catherine Wilson in Aeon:

Catherine Wilson in Aeon: Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes: For anyone with a platform,

For anyone with a platform,  The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers.

The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers. B

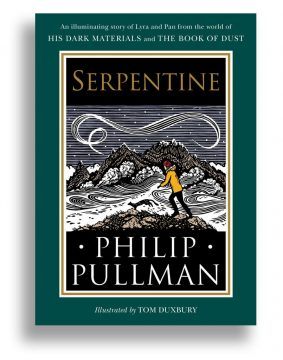

B Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “

Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “ ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the

ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the  In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400.

In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400. The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die

The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die  Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world.

Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world. When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.

When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.