This pandemic changes everything, we can’t go back to the way we were. That’s what everyone is saying. Well, not everyone, but I don’t know how many times I’ve read some version of that over the past month.

I would like to reflect on that theme, albeit in perhaps and oblique and impressionist manner. I want to begin by invoking a recent essay in which Marc Andreessen urges us to “reboot the American Dream.” Then I move back half a century and look at Walt Disney’s version of, well, the American Dream. I return to the present through an essay by Ezra Klein and conclude with a video in which Sean O’Sullivan talks of how he came to form an NGO that worked on building Iraq early in this millennium.

Marc Andreessen: Let’s Build Something!

Roughly two weeks ago a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist, Marc Andreessen, issued a call to action, It’s Time to Build, which has been getting a lot of action, pro, con, and sideways. Here’s how it opens:

Every Western institution was unprepared for the coronavirus pandemic, despite many prior warnings. This monumental failure of institutional effectiveness will reverberate for the rest of the decade, but it’s not too early to ask why, and what we need to do about it.

Many of us would like to pin the cause on one political party or another, on one government or another. But the harsh reality is that it all failed — no Western country, or state, or city was prepared — and despite hard work and often extraordinary sacrifice by many people within these institutions. So the problem runs deeper than your favorite political opponent or your home nation. Read more »

Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age.

Before 2015, few people would have thought of not finishing college as a public-health issue. That changed because of research done by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, economists at Princeton who are also married. For the past six years, they have been collaboratively researching an alarming long-term increase in what they call “deaths of despair” — suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholism-related illnesses — among white non-Hispanic Americans without a bachelor’s degree in middle age. By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad.

By the last week of January, Rob DeLeo knew it was going to get bad. The Covid-19 lockdown on the largest population on earth with the shortest possible notice has completed five weeks. Overnight, a medical pandemic was made into an economic and humanitarian disaster of immense proportions. It is time we took stock.

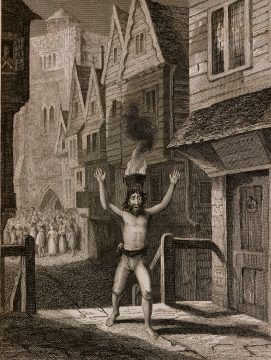

The Covid-19 lockdown on the largest population on earth with the shortest possible notice has completed five weeks. Overnight, a medical pandemic was made into an economic and humanitarian disaster of immense proportions. It is time we took stock. ISTANBUL — For the past four years I have been writing a historical novel set in 1901 during what is known as the third plague pandemic, an outbreak of bubonic plague that killed millions of people in Asia but not very many in Europe. Over the last two months, friends and family, editors and journalists who know the subject of that novel, “Nights of Plague,” have been asking me a barrage of questions about pandemics. They are most curious about similarities between the current coronavirus pandemic and the historical outbreaks of plague and cholera. There is an overabundance of similarities. Throughout human and literary history what makes pandemics alike is not mere commonality of germs and viruses but that our initial responses were always the same. The initial response to the outbreak of a pandemic has always been denial. National and local governments have always been late to respond and have distorted facts and manipulated figures to deny the existence of the outbreak. In the early pages of “A Journal of the Plague Year,” the single most illuminating work of literature ever written on contagion and human behavior, Daniel Defoe reports that in 1664, local authorities in some neighborhoods of London tried to make the number of plague deaths appear lower than it was by registering other, invented diseases as the recorded cause of death.

ISTANBUL — For the past four years I have been writing a historical novel set in 1901 during what is known as the third plague pandemic, an outbreak of bubonic plague that killed millions of people in Asia but not very many in Europe. Over the last two months, friends and family, editors and journalists who know the subject of that novel, “Nights of Plague,” have been asking me a barrage of questions about pandemics. They are most curious about similarities between the current coronavirus pandemic and the historical outbreaks of plague and cholera. There is an overabundance of similarities. Throughout human and literary history what makes pandemics alike is not mere commonality of germs and viruses but that our initial responses were always the same. The initial response to the outbreak of a pandemic has always been denial. National and local governments have always been late to respond and have distorted facts and manipulated figures to deny the existence of the outbreak. In the early pages of “A Journal of the Plague Year,” the single most illuminating work of literature ever written on contagion and human behavior, Daniel Defoe reports that in 1664, local authorities in some neighborhoods of London tried to make the number of plague deaths appear lower than it was by registering other, invented diseases as the recorded cause of death. Over at Columbia University’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute:

Over at Columbia University’s Weatherhead East Asian Institute: Chris Lehman in TNR:

Chris Lehman in TNR: Dirk Philipsen in Aeon:

Dirk Philipsen in Aeon: In 1937 the art critic

In 1937 the art critic  Perhaps more important than the way Dryer’s paintings have continued to live in the memories of those who saw them in the Eighties and early Nineties is the way her name has lived on as a kind of password among certain younger abstract painters who may never, or only rarely, have had a chance to see her work in person. In an article published in the Brooklyn Rail in 2012, the English painter and critic David Rhodes recalled his impression, reading in London about Dryer’s work years before, “that New York had done it again; a tradition was being recoined and revitalized,” thanks to her “taking a long look at abstraction and quickly coming up with something fresh and new.” Her reputation continued to circulate, sub rosa, among painters hoping to work with abstraction without bombast or the illusion of progress, to paint in ways that might be at once more intelligent and more full of feeling, more playful and yet more earnest.

Perhaps more important than the way Dryer’s paintings have continued to live in the memories of those who saw them in the Eighties and early Nineties is the way her name has lived on as a kind of password among certain younger abstract painters who may never, or only rarely, have had a chance to see her work in person. In an article published in the Brooklyn Rail in 2012, the English painter and critic David Rhodes recalled his impression, reading in London about Dryer’s work years before, “that New York had done it again; a tradition was being recoined and revitalized,” thanks to her “taking a long look at abstraction and quickly coming up with something fresh and new.” Her reputation continued to circulate, sub rosa, among painters hoping to work with abstraction without bombast or the illusion of progress, to paint in ways that might be at once more intelligent and more full of feeling, more playful and yet more earnest. HBO’s “Bad Education,” coming out on Saturday, is a dramatization of a real-life school-district scandal that occurred on Long Island. I took note of the scandal when it first unfolded, in the early two-thousands, because I graduated from the institution at its center, Roslyn High School, three decades earlier (though my family connection to the town was already long over). What’s fascinating and significant about the film, which is written by Mike Makowsky and directed by Cory Finley, is that it takes a serious look not at Roslyn’s idiosyncrasies (“Bad Education” doesn’t dwell on local curiosities) but at the traits that Roslyn shares with more or less every prosperous suburb in America. It’s a story of aspirations and dreams, of the striving for wealth and the perpetuation of its privileges, and of the systems by which that process of heightened stratification, of upward mobility for those already on top, is sustained. It’s also a movie that exemplifies the unchallenged movie convention of distilling a complex story into information snippets, each with its own specific emotional orientation, that fit together so precisely and so tightly that, rather than exploring its implications, it seals them out.

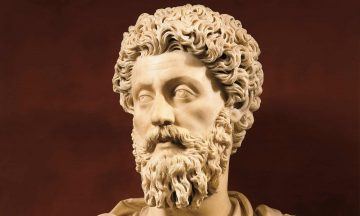

HBO’s “Bad Education,” coming out on Saturday, is a dramatization of a real-life school-district scandal that occurred on Long Island. I took note of the scandal when it first unfolded, in the early two-thousands, because I graduated from the institution at its center, Roslyn High School, three decades earlier (though my family connection to the town was already long over). What’s fascinating and significant about the film, which is written by Mike Makowsky and directed by Cory Finley, is that it takes a serious look not at Roslyn’s idiosyncrasies (“Bad Education” doesn’t dwell on local curiosities) but at the traits that Roslyn shares with more or less every prosperous suburb in America. It’s a story of aspirations and dreams, of the striving for wealth and the perpetuation of its privileges, and of the systems by which that process of heightened stratification, of upward mobility for those already on top, is sustained. It’s also a movie that exemplifies the unchallenged movie convention of distilling a complex story into information snippets, each with its own specific emotional orientation, that fit together so precisely and so tightly that, rather than exploring its implications, it seals them out. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the last famous Stoic philosopher of antiquity. During the last 14 years of his life he faced one of the worst plagues in European history. The Antonine Plague, named after him, was probably caused by a strain of the smallpox virus. It’s estimated to have killed up to 5 million people, possibly including Marcus himself. From AD166 to around AD180, repeated outbreaks occurred throughout the known world. Roman historians describe the legions being devastated, and entire towns and villages being depopulated and going to ruin. Rome itself was particularly badly affected, carts leaving the city each day piled high with dead bodies.

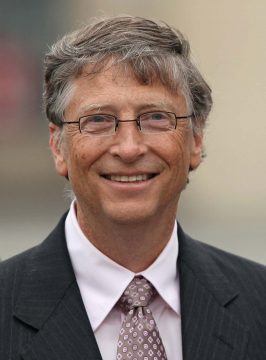

The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was the last famous Stoic philosopher of antiquity. During the last 14 years of his life he faced one of the worst plagues in European history. The Antonine Plague, named after him, was probably caused by a strain of the smallpox virus. It’s estimated to have killed up to 5 million people, possibly including Marcus himself. From AD166 to around AD180, repeated outbreaks occurred throughout the known world. Roman historians describe the legions being devastated, and entire towns and villages being depopulated and going to ruin. Rome itself was particularly badly affected, carts leaving the city each day piled high with dead bodies. The coronavirus pandemic pits all of humanity against the virus. The damage to health, wealth, and well-being has already been enormous. This is like a world war, except in this case, we’re all on the same side. Everyone can work together to learn about the disease and develop tools to fight it. I see global innovation as the key to limiting the damage. This includes innovations in testing, treatments, vaccines, and policies to limit the spread while minimizing the damage to economies and well-being.

The coronavirus pandemic pits all of humanity against the virus. The damage to health, wealth, and well-being has already been enormous. This is like a world war, except in this case, we’re all on the same side. Everyone can work together to learn about the disease and develop tools to fight it. I see global innovation as the key to limiting the damage. This includes innovations in testing, treatments, vaccines, and policies to limit the spread while minimizing the damage to economies and well-being.