by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

The following is the continuation of an interview with Tom, a pilot who has largely withdrawn to a small piece of land in rural South Dakota. Parts I and II can be found here and here.

Interviewer: I’d like to ask how you would tell the story of your inner jukebox—perhaps under the title “The Inner Jukebox: A Bildungsroman.”

Hermit: Ah, the inner jukebox, its bearings rusty and contacts dusty. That thing used to roll on an endless reel, telling me and shaping how I feel.

Music, I really used to think, is one of mankind’s greatest achievements. Now I just think less, it seems, or about different things. But even as I give music less thought, it surely is very special.

Music can fit a mood, bend or even break a mood, make a new mood, take you places—what a thing! But at the same time, there is always the chance of going missing as in other ways I have described. In no way have I shunned or avoided music, but I do not seek its warp-voyager quality any longer. I must say that I am not beyond being grabbed and taken for a ride from time to time, however.

The soundtrack you mentioned, I used to make so many playlists to fit time, place, and mood, and it never failed that by the time I had finished making the perfect playlist, it no longer fit those things. I might conclude that it has everything to do with the aforementioned coloring; that the more one truly accepts their immediate surrounding and circumstance, there might just not be a track cued up (unless on an elevator, help us).

All of that said, it can be counted on that I am nearly always narrating my plodding with ditties and tunes spontaneously coined.

Interviewer: On the subject of where the mind goes (and warp-voyagers), what are the thought patterns that recur in hermitude?

Hermit: This is perhaps the one area in which I struggle the most. Thought.

I said just before that I think less, or about other things now. Not true, that, upon reflection. I interact with my thoughts less, but there is no evidence that I think less. Thank you for reminding me. Read more »

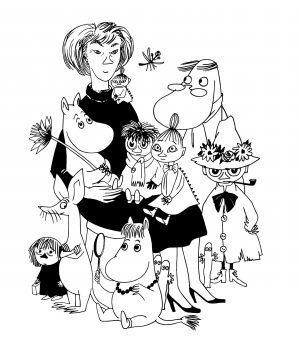

In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.

In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.

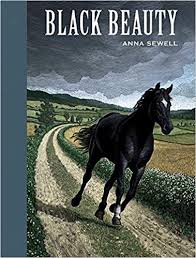

It is perhaps partially owing to this plain style that Black Beauty is now classified as children’s literature. (But it is perhaps owing, too, to a modern day disdain for simple things like manual labor, animals, imagination, and kindness.) During the mid-Victorian era, children’s literature was a still-developing category of books. The fact is that Sewell was writing for men. And she was read by them, too, as one review attests: “Both men and boys read it with the greatest avidity, and many declare it to be ‘the best book in the world’.”

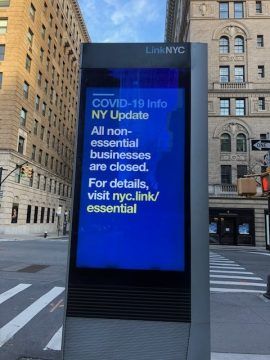

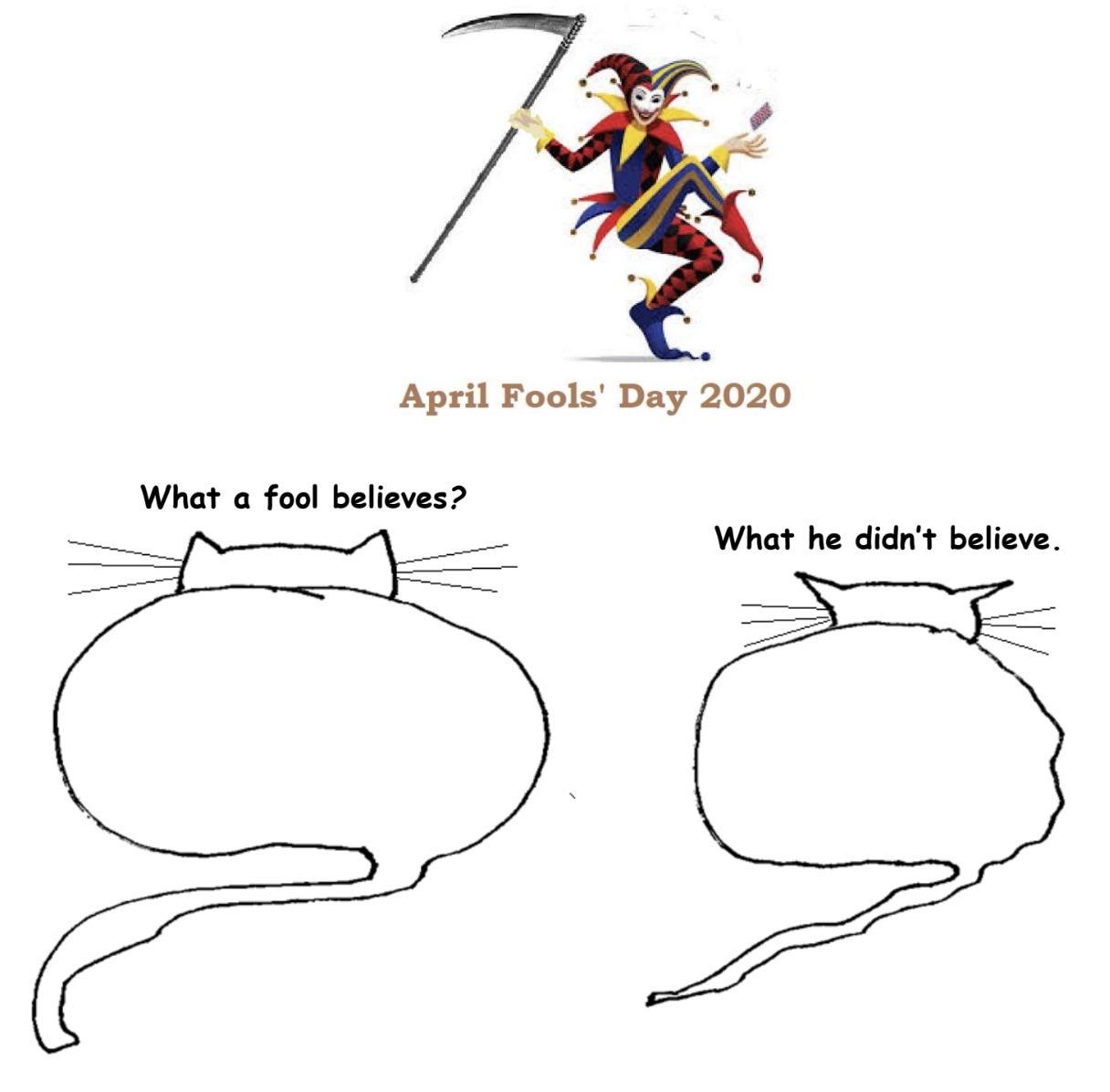

It is perhaps partially owing to this plain style that Black Beauty is now classified as children’s literature. (But it is perhaps owing, too, to a modern day disdain for simple things like manual labor, animals, imagination, and kindness.) During the mid-Victorian era, children’s literature was a still-developing category of books. The fact is that Sewell was writing for men. And she was read by them, too, as one review attests: “Both men and boys read it with the greatest avidity, and many declare it to be ‘the best book in the world’.” Long before the first reports of a new flu-like illness in China’s Hubei province, a bat—or perhaps a whole colony of them—was flying around the region carrying a new type of coronavirus. At the time, the virus was not yet dangerous to humans. Then, around the end of November, it underwent a slight additional mutation, evolving into the viral strain we now call SARS-CoV-2. With that flip of viral RNA, so began the COVID-19 pandemic. As in almost every outbreak, the mutations that set off this global crisis went undetected at first, even though the family of coronaviruses was already known to cause a variety of human diseases. “These viruses have long been understudied and have not been given the attention or funding they have deserved,” Craig Wilen, a virologist at Yale University, told me.

Long before the first reports of a new flu-like illness in China’s Hubei province, a bat—or perhaps a whole colony of them—was flying around the region carrying a new type of coronavirus. At the time, the virus was not yet dangerous to humans. Then, around the end of November, it underwent a slight additional mutation, evolving into the viral strain we now call SARS-CoV-2. With that flip of viral RNA, so began the COVID-19 pandemic. As in almost every outbreak, the mutations that set off this global crisis went undetected at first, even though the family of coronaviruses was already known to cause a variety of human diseases. “These viruses have long been understudied and have not been given the attention or funding they have deserved,” Craig Wilen, a virologist at Yale University, told me. Scientists agree that the main means by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumps from an infected person to its next host is

Scientists agree that the main means by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumps from an infected person to its next host is  Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me.

Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me. Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object. I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.) Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.  by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice.

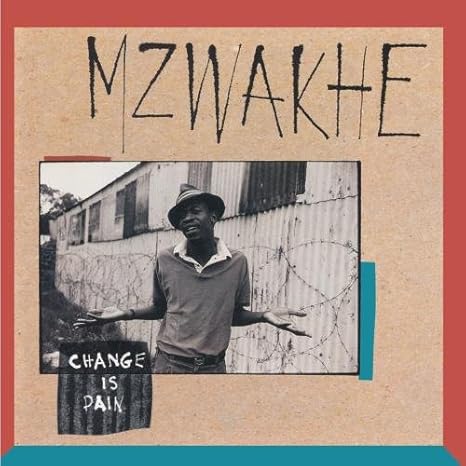

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America. Of all the resources lacking in the Covid-19 pandemic, the one most desperately needed in the United States is a unified national strategy, as well as the confident, coherent and consistent leadership to see it carried out. The country cannot go from one mixed-message news briefing to the next, and from tweet to tweet, to define policy priorities. It needs a science-based plan that looks to the future rather than merely reacting to latest turn in the crisis.

Of all the resources lacking in the Covid-19 pandemic, the one most desperately needed in the United States is a unified national strategy, as well as the confident, coherent and consistent leadership to see it carried out. The country cannot go from one mixed-message news briefing to the next, and from tweet to tweet, to define policy priorities. It needs a science-based plan that looks to the future rather than merely reacting to latest turn in the crisis.