Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

This year we give thanks for space. (We’ve previously given thanks for the Standard Model Lagrangian, Hubble’s Law, the Spin-Statistics Theorem, conservation of momentum, effective field theory, the error bar, gauge symmetry, Landauer’s Principle, the Fourier Transform, Riemannian Geometry, the speed of light, the Jarzynski equality, and the moons of Jupiter.)

This year we give thanks for space. (We’ve previously given thanks for the Standard Model Lagrangian, Hubble’s Law, the Spin-Statistics Theorem, conservation of momentum, effective field theory, the error bar, gauge symmetry, Landauer’s Principle, the Fourier Transform, Riemannian Geometry, the speed of light, the Jarzynski equality, and the moons of Jupiter.)

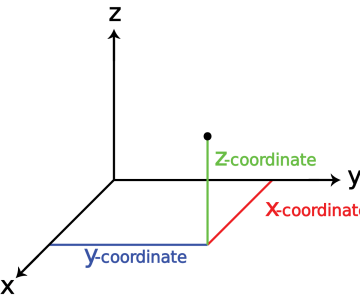

Even when we restrict to essentially scientific contexts, “space” can have a number of meanings. In a tangible sense, it can mean outer space — the final frontier, that place we could go away from the Earth, where the stars and other planets are located. In a much more abstract setting, mathematicians use “space” to mean some kind of set with additional structure, like Hilbert space or the space of all maps between two manifolds. Here we’re aiming in between, using “space” to mean the three-dimensional manifold in which physical objects are located, at least as far as our observable universe is concerned.

That last clause reminds us that there are some complications here.

More here.

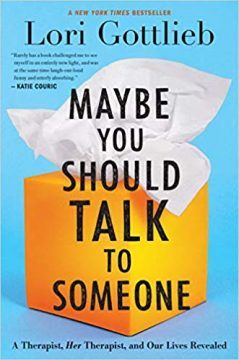

Cal Flyn: We’re here to talk about the best self-help books of 2019. Before we start, let’s define our terms: what does ‘self-help’ mean to you?

Cal Flyn: We’re here to talk about the best self-help books of 2019. Before we start, let’s define our terms: what does ‘self-help’ mean to you? Something strange is afoot when America turns to journalists for advice in surviving a holiday devoted nearly entirely to eating good food. Politics has rendered Thanksgiving something to be dreaded. Given the purpose of the holiday, this is tragic. Can anything be done to save Thanksgiving from our partisan divisions?

Something strange is afoot when America turns to journalists for advice in surviving a holiday devoted nearly entirely to eating good food. Politics has rendered Thanksgiving something to be dreaded. Given the purpose of the holiday, this is tragic. Can anything be done to save Thanksgiving from our partisan divisions? When I was a child, Thanksgiving was simple. It was about turkey and dressing, love and laughter, a time for the family to gather around a feast and be thankful for the year that had passed and be hopeful for the year to come. In school, the story we learned was simple, too: Pilgrims and Native Americans came together to give thanks. We made pictures of the gathering, everyone smiling. We colored turkeys or made them out of construction paper. We sometimes had a mini-feast in class. I thought it was such a beautiful story: People reaching across race and culture to share with one another, to commune with one another. But that is not the full story of Thanksgiving. Like so much of American history, the story has had its least attractive features winnow away — white people have been centered in the narrative and all atrocity has been politely papered over.

When I was a child, Thanksgiving was simple. It was about turkey and dressing, love and laughter, a time for the family to gather around a feast and be thankful for the year that had passed and be hopeful for the year to come. In school, the story we learned was simple, too: Pilgrims and Native Americans came together to give thanks. We made pictures of the gathering, everyone smiling. We colored turkeys or made them out of construction paper. We sometimes had a mini-feast in class. I thought it was such a beautiful story: People reaching across race and culture to share with one another, to commune with one another. But that is not the full story of Thanksgiving. Like so much of American history, the story has had its least attractive features winnow away — white people have been centered in the narrative and all atrocity has been politely papered over. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the United Kingdom had eradicated the infectious viral disease rubella. The following year, it similarly designated the country as measles-free after confirmed cases numbered fewer than 125 for the second consecutive year. Immunization rates in UK children were high at that time. They had slumped to a nadir in the mid-2000s following the false assertion in 1998 that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was linked to autism. But by 2016, more than 95% of the country’s 5-year-olds had received one dose of MMR, and roughly 85% had received the pre-school booster that maximizes immunity. When 95% of a population is immune to measles, the disease cannot spread. This is known as herd immunity, and it is the cornerstone of the WHO’s long-held plan to eradicate measles globally. Achieving this would rid the world of a very serious disease, for which 1 in 1,000 cases is fatal. In 2010, eradication was considered achievable by 2020. But that time is almost here, and the disease is not close to being eradicated. In fact, it is on the rise.

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the United Kingdom had eradicated the infectious viral disease rubella. The following year, it similarly designated the country as measles-free after confirmed cases numbered fewer than 125 for the second consecutive year. Immunization rates in UK children were high at that time. They had slumped to a nadir in the mid-2000s following the false assertion in 1998 that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine was linked to autism. But by 2016, more than 95% of the country’s 5-year-olds had received one dose of MMR, and roughly 85% had received the pre-school booster that maximizes immunity. When 95% of a population is immune to measles, the disease cannot spread. This is known as herd immunity, and it is the cornerstone of the WHO’s long-held plan to eradicate measles globally. Achieving this would rid the world of a very serious disease, for which 1 in 1,000 cases is fatal. In 2010, eradication was considered achievable by 2020. But that time is almost here, and the disease is not close to being eradicated. In fact, it is on the rise. On best estimates, there are some 270 million cars currently in the US, with 90 percent of households owning at least one. Most own several. The low fuel prices produced by the fracking boom encouraged the use of SUVs and trucks, which now account for more than 60 percent of vehicle sales.

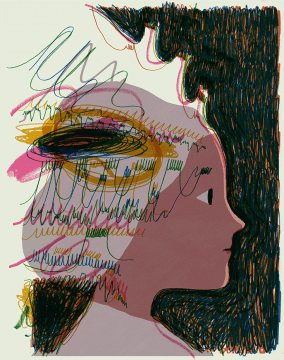

On best estimates, there are some 270 million cars currently in the US, with 90 percent of households owning at least one. Most own several. The low fuel prices produced by the fracking boom encouraged the use of SUVs and trucks, which now account for more than 60 percent of vehicle sales. SINCE 2006, Kelly Copper and Pavol Liška, collaborating as the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, have created brainy and ebullient works for stage, film, and video, aerating serious conceptual heft with an oddball comedic sensibility. For the directing-and-writing duo, scripts have never been hard-and-fast things. Take the one for their epic nine-part video Life and Times (2009–15): The words were transcribed from phone conversations between Liška and company member Kristin Worrall, during which the latter recounted the (often banal) details of her life thus far. What else would one expect from a team whose moniker is lifted from a poster that appears in Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927) announcing an opportunity to join the Nature Theater of Oklahoma: “Anyone who wants to become an artist should contact us! We are a theater that can make use of everyone, each in his place!”

SINCE 2006, Kelly Copper and Pavol Liška, collaborating as the Nature Theater of Oklahoma, have created brainy and ebullient works for stage, film, and video, aerating serious conceptual heft with an oddball comedic sensibility. For the directing-and-writing duo, scripts have never been hard-and-fast things. Take the one for their epic nine-part video Life and Times (2009–15): The words were transcribed from phone conversations between Liška and company member Kristin Worrall, during which the latter recounted the (often banal) details of her life thus far. What else would one expect from a team whose moniker is lifted from a poster that appears in Franz Kafka’s Amerika (1927) announcing an opportunity to join the Nature Theater of Oklahoma: “Anyone who wants to become an artist should contact us! We are a theater that can make use of everyone, each in his place!” “In the short term, it would be very positive for the housing market,” says Lawrence Yun, the National Association of Realtors chief economist. He says his group’s

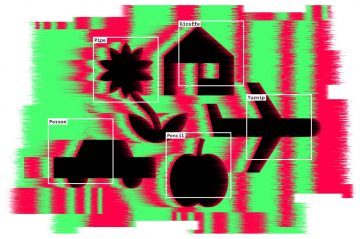

“In the short term, it would be very positive for the housing market,” says Lawrence Yun, the National Association of Realtors chief economist. He says his group’s  A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’.

A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Wall Street

Wall Street  Whether or not she believes them, Chu’s initial theses lead her into a series of chapters in which she theorizes, among other things, gender transition according to the recuperated principles of her personally curated second-wave feminism. Chu quotes her icon Solanas on Candy Darling (1944–1974), an actor and trans woman associated with Warhol’s Factory scene: “[A] perfect victim of male suppression.” (Chu says the epithet was spoken “admiringly”; it’s hard to see how.) Females inclines toward this view, with a twist. Trans women come across as the dupes of patriarchal gender norms, consuming and reproducing the stereotyped and anti-feminist images of the beauty industry. In that mode, Chu describes the YouTube makeup artist Gigi Gorgeous as “in the most technical sense of this phrase, a dumb blonde.” She only recuperates this, frankly, sexist jeer by universalizing its principle: “From the perspective of gender, then, we’re all dumb blondes.” Trading on an alt-right lexicon borrowed from The Matrix, she refers to hormone therapy as “plugging […] back into the simulation.” The charge that gender transition reinforces sexist stereotypes and retrograde gender norms is an old accusation; it doesn’t get more convincing when the person saying it happens to be trans herself. Chu updates this anti-trans feminism by generalizing its theses: she agrees with the accusation that transition sustains the objectification of women, and submits that there’s no way out, for trans people or anybody else.

Whether or not she believes them, Chu’s initial theses lead her into a series of chapters in which she theorizes, among other things, gender transition according to the recuperated principles of her personally curated second-wave feminism. Chu quotes her icon Solanas on Candy Darling (1944–1974), an actor and trans woman associated with Warhol’s Factory scene: “[A] perfect victim of male suppression.” (Chu says the epithet was spoken “admiringly”; it’s hard to see how.) Females inclines toward this view, with a twist. Trans women come across as the dupes of patriarchal gender norms, consuming and reproducing the stereotyped and anti-feminist images of the beauty industry. In that mode, Chu describes the YouTube makeup artist Gigi Gorgeous as “in the most technical sense of this phrase, a dumb blonde.” She only recuperates this, frankly, sexist jeer by universalizing its principle: “From the perspective of gender, then, we’re all dumb blondes.” Trading on an alt-right lexicon borrowed from The Matrix, she refers to hormone therapy as “plugging […] back into the simulation.” The charge that gender transition reinforces sexist stereotypes and retrograde gender norms is an old accusation; it doesn’t get more convincing when the person saying it happens to be trans herself. Chu updates this anti-trans feminism by generalizing its theses: she agrees with the accusation that transition sustains the objectification of women, and submits that there’s no way out, for trans people or anybody else. Lucy Ellmann’s new novel, Ducks, Newburyport, does not, despite the claims of some reviewers, consist of a single sentence (I counted 880). But it does contain one very long one: a comma-strewn stream that follows the thoughts of an Ohioan housewife during the first few months of 2017. While she bakes the pies she sells to local diners she worries about her four children, considers language usage (the difference between ‘envy’ and ‘jealousy’ and ‘affect’ and ‘effect’; the misuse of ‘enormity’), thinks lovingly about her husband, Leo, mourns her dead parents, and despairs over the state of the environment, Trump’s presidency, mass shootings, and the historic genocides of indigenous people. ‘A lot of people think all I think about is pie,’ she thinks, ‘when really it’s my spinal brain doing most of the peeling and caramelising and baking and flipping, while I just stand there spiralling into a panic about my mom and animal extinctions and the Second Amendment just like everybody else.’

Lucy Ellmann’s new novel, Ducks, Newburyport, does not, despite the claims of some reviewers, consist of a single sentence (I counted 880). But it does contain one very long one: a comma-strewn stream that follows the thoughts of an Ohioan housewife during the first few months of 2017. While she bakes the pies she sells to local diners she worries about her four children, considers language usage (the difference between ‘envy’ and ‘jealousy’ and ‘affect’ and ‘effect’; the misuse of ‘enormity’), thinks lovingly about her husband, Leo, mourns her dead parents, and despairs over the state of the environment, Trump’s presidency, mass shootings, and the historic genocides of indigenous people. ‘A lot of people think all I think about is pie,’ she thinks, ‘when really it’s my spinal brain doing most of the peeling and caramelising and baking and flipping, while I just stand there spiralling into a panic about my mom and animal extinctions and the Second Amendment just like everybody else.’ Everyone wants to know how this is going to end, but no one has an answer. I know this: We are going to be living with the consequences of trauma for years. They can scrub the walls clean of the graffiti, but the horrific images will continue to eat away at us: a protester shot at point-blank range; a tear-gas canister erupting onto someone’s back, burning the flesh blue-black; a man pressed to the ground, bleeding profusely and teeth knocked out; a pair of punctured eye goggles. The trials for those who participated in the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 have only just ended. We will spend the next couple of years watching the government throw hundreds, if not thousands, in jail.

Everyone wants to know how this is going to end, but no one has an answer. I know this: We are going to be living with the consequences of trauma for years. They can scrub the walls clean of the graffiti, but the horrific images will continue to eat away at us: a protester shot at point-blank range; a tear-gas canister erupting onto someone’s back, burning the flesh blue-black; a man pressed to the ground, bleeding profusely and teeth knocked out; a pair of punctured eye goggles. The trials for those who participated in the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 have only just ended. We will spend the next couple of years watching the government throw hundreds, if not thousands, in jail. On Aug. 15, 1914, a servant set fire to Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s sprawling estate in Spring Green, Wis. Julian Carlton also took up an ax and murdered seven people, among them Wright’s mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her two children. Wright was already famous, as this country’s preeminent architect, and notorious, for leaving his wife and children for Cheney, with whom he lived openly and, by contemporary standards, shamelessly. The massacre made headlines around the country, and though Carlton’s motives remain obscure and unknowable to this day, the carnage was held up by many as divine retribution for Wright’s marital misbehavior.

On Aug. 15, 1914, a servant set fire to Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s sprawling estate in Spring Green, Wis. Julian Carlton also took up an ax and murdered seven people, among them Wright’s mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her two children. Wright was already famous, as this country’s preeminent architect, and notorious, for leaving his wife and children for Cheney, with whom he lived openly and, by contemporary standards, shamelessly. The massacre made headlines around the country, and though Carlton’s motives remain obscure and unknowable to this day, the carnage was held up by many as divine retribution for Wright’s marital misbehavior. In one important way, the recipient of a heart transplant ignores its new organ: Its nervous system usually doesn’t rewire to communicate with it. The 40,000 neurons controlling a heart operate so perfectly, and are so self-contained, that a heart can be cut out of one body, placed into another, and continue to function perfectly, even in the absence of external control, for a decade or more. This seems necessary: The parts of our nervous system managing our most essential functions behave like a Swiss watch, precisely timed and impervious to perturbations. Chaotic behavior has been throttled out.

In one important way, the recipient of a heart transplant ignores its new organ: Its nervous system usually doesn’t rewire to communicate with it. The 40,000 neurons controlling a heart operate so perfectly, and are so self-contained, that a heart can be cut out of one body, placed into another, and continue to function perfectly, even in the absence of external control, for a decade or more. This seems necessary: The parts of our nervous system managing our most essential functions behave like a Swiss watch, precisely timed and impervious to perturbations. Chaotic behavior has been throttled out. The so-called Muscovy duck is so called not in view of its homeland in the vicinity of Moscow –for in fact it is native to Central and South America– but rather in mistranslation of its Latin designation, Anas moschata, the “musky duck”, thus “not transferred from Muscovia,” as the English naturalist John Ray writes in 1713, “but from the rather strong musk odour it exudes.”

The so-called Muscovy duck is so called not in view of its homeland in the vicinity of Moscow –for in fact it is native to Central and South America– but rather in mistranslation of its Latin designation, Anas moschata, the “musky duck”, thus “not transferred from Muscovia,” as the English naturalist John Ray writes in 1713, “but from the rather strong musk odour it exudes.”