Holly Case in Aeon:

Holly Case in Aeon:

In August 1989, just a few weeks before the Berlin Wall came down, the East German writer Christa Wolf offered her view on the possibility of German reunification. Wolf had remained a communist party member until June that year, and even thereafter she espoused her Leftist convictions to the shrinking number of people who openly shared them. She firmly stated her opposition to the merger of the two Germanys. ‘[R]eunification – as the annexation of the smaller, poorer part of Germany to the larger, wealthier one – would render the self-critical treatment of our past much more difficult,’ she argued. The people of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) should instead try on their own terms to realise the dream of a truly ‘democratic socialism’ in a state where ‘contradiction’ can be not only ‘tolerated’ but even ‘made productive’. If the GDR were to simply disappear, the necessary opposite – Germany’s own ‘double meaning’ (a recurring theme in her literary work) – would disappear along with it, to catastrophic effect. Collapsing the two Germanys into one, in other words, would destroy it.

Just as Wolf decried the merger of the two Germanys, several decades earlier Herbert Marcuse mourned the merger of two dimensions in his book One-Dimensional Man (1964). Marcuse, a German philosopher of the Frankfurt School whose members devised a form of Western Marxist philosophy known as critical theory, offered an analysis of the homogenising effects of consumerism.

More here.

Adolph Reed Jr. in The New Republic:

Adolph Reed Jr. in The New Republic: J. Daniel Elam in Public Books:

J. Daniel Elam in Public Books:

“A

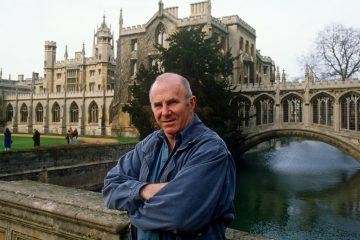

“A You can take the writer out of California but you can’t take California out of the writer — or at least so I prefer to imagine, in my romantic fashion, during these dark days in which everything beautiful about the Golden State seems to be burning.

You can take the writer out of California but you can’t take California out of the writer — or at least so I prefer to imagine, in my romantic fashion, during these dark days in which everything beautiful about the Golden State seems to be burning. “A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing,” he wrote. “Those who lack humor are without judgment and should be trusted with nothing.”

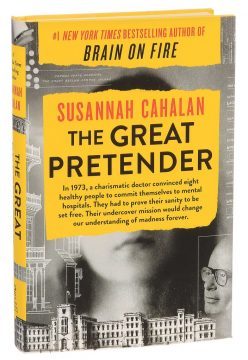

“A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing,” he wrote. “Those who lack humor are without judgment and should be trusted with nothing.” Books about mental illness often reflect on how reality is experienced. In addition to the standard questions — What do we know, and how do we know it? — is another layer of inquiry: What do we know about our own minds, and what if it isn’t true? In her first book,

Books about mental illness often reflect on how reality is experienced. In addition to the standard questions — What do we know, and how do we know it? — is another layer of inquiry: What do we know about our own minds, and what if it isn’t true? In her first book,  The warming of the planet currently spread across seven continents, four oceans, and twenty-four time zones is the product of a fossil-fueled capitalist economy that over the past two hundred years has stuffed the world with riches beyond the wit of man to marvel at or measure. The wealth of nations comes at a steep price—typhoons in the Philippine Sea, Category 5 hurricanes in the Caribbean, massive flooding in Kansas and Uttar Pradesh, forests disappearing in Sumatra and Brazil, unbearable heat in Paris, uncontrollable wildfires in California, unbreathable air in Mexico City and Beijing. The capitalist dynamic is both cause of our prosperous good fortune and means of our probable destruction, the damage in large part the work of

The warming of the planet currently spread across seven continents, four oceans, and twenty-four time zones is the product of a fossil-fueled capitalist economy that over the past two hundred years has stuffed the world with riches beyond the wit of man to marvel at or measure. The wealth of nations comes at a steep price—typhoons in the Philippine Sea, Category 5 hurricanes in the Caribbean, massive flooding in Kansas and Uttar Pradesh, forests disappearing in Sumatra and Brazil, unbearable heat in Paris, uncontrollable wildfires in California, unbreathable air in Mexico City and Beijing. The capitalist dynamic is both cause of our prosperous good fortune and means of our probable destruction, the damage in large part the work of  1. HE MET HIS FIRST WIFE IN KINDERGARTEN.

1. HE MET HIS FIRST WIFE IN KINDERGARTEN. Food is a many-splendored thing, and its meanings too are manifold. It upholds the life of both our higher and lower selves, and most things in between. Indeed, the ways we think about our food might well be taken as a rough index of what we consider those two words

Food is a many-splendored thing, and its meanings too are manifold. It upholds the life of both our higher and lower selves, and most things in between. Indeed, the ways we think about our food might well be taken as a rough index of what we consider those two words  Looking and listening around today, one sometimes gets the impression that the ‘historical moment’ of 1989, with all its excitement and happiness, never occurred – that the event witnessed by many of us has vanished under a mountain of interpretation and reflection; that ‘in fact’ all that happened on the streets of Berlin, Prague, Warsaw, Bucharest and elsewhere was mere self-deception, an illusion, surreality. Despite all the documentaries, the newsreels and interviews, the experience of people appears to have largely been forgotten – people who first crossed the open border, striding enthusiastically or strolling, exploring a world that had been closed to them their entire lives, the thrill of liberty, of the freedom of movement, of reading newspapers they never had access to before, of visiting relatives in the West.

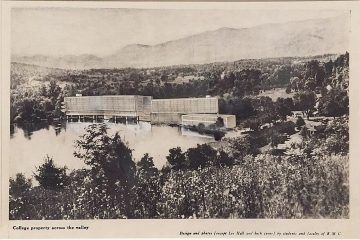

Looking and listening around today, one sometimes gets the impression that the ‘historical moment’ of 1989, with all its excitement and happiness, never occurred – that the event witnessed by many of us has vanished under a mountain of interpretation and reflection; that ‘in fact’ all that happened on the streets of Berlin, Prague, Warsaw, Bucharest and elsewhere was mere self-deception, an illusion, surreality. Despite all the documentaries, the newsreels and interviews, the experience of people appears to have largely been forgotten – people who first crossed the open border, striding enthusiastically or strolling, exploring a world that had been closed to them their entire lives, the thrill of liberty, of the freedom of movement, of reading newspapers they never had access to before, of visiting relatives in the West. Grouping writers into “schools” has always been problematic. The so-called Black Mountain poets never identified themselves as such, but the facts of their union spring from a remarkable instance of artistic community: Black Mountain College and the web of interactions the place occasioned. Founded in the mountains of western North Carolina in 1933 and closed by 1956, the college was one of the most significant experiments in arts and education of the twentieth century. In recent years, a number of international exhibitions and publications have showcased the range of artwork produced at the college’s two campuses, the first situated in the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly, and the second at Lake Eden in the Swannanoa Valley. The list of famous names associated with Black Mountain is as impressive as it is unlikely, given that the college never housed more than a hundred students and faculty at a time, often far fewer.

Grouping writers into “schools” has always been problematic. The so-called Black Mountain poets never identified themselves as such, but the facts of their union spring from a remarkable instance of artistic community: Black Mountain College and the web of interactions the place occasioned. Founded in the mountains of western North Carolina in 1933 and closed by 1956, the college was one of the most significant experiments in arts and education of the twentieth century. In recent years, a number of international exhibitions and publications have showcased the range of artwork produced at the college’s two campuses, the first situated in the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly, and the second at Lake Eden in the Swannanoa Valley. The list of famous names associated with Black Mountain is as impressive as it is unlikely, given that the college never housed more than a hundred students and faculty at a time, often far fewer.

Today, the problem of existential homelessness has become acute. Growing rates of anxiety, loneliness, and suicide offer statistical confirmation. Facebook and Amazon are among the largest and most powerful corporations on the planet, yet the realization is dawning that social media “friends” are poor substitutes for the real thing and that man cannot live by online shopping alone. (See “

Today, the problem of existential homelessness has become acute. Growing rates of anxiety, loneliness, and suicide offer statistical confirmation. Facebook and Amazon are among the largest and most powerful corporations on the planet, yet the realization is dawning that social media “friends” are poor substitutes for the real thing and that man cannot live by online shopping alone. (See “ Simone de Beauvoir spent more time talking about inauthentic love than authentic. But that is because she thought authentic love is so hard to achieve. From the vantage point of 2017, aspects of Beauvoir’s view of authentic love look rather dated and pessimistic: for one thing, it presents men and women in binary terms that are unlikely to resound with many readers. Today’s women have greater access to education and employment than women did in 1949, and may be less likely to see love as life, as Beauvoir charged, instead of a part of life. Although structural inequality persists, relationships between men and women – or men and men, or women and women, etc. – theoretically have better chances of proceeding on an equal footing. But nevertheless many cultural portrayals of love (from Puccini to pop) continue to depict it as a game between unequals – as conquest or domination, seduction or entrapment – where the boundaries are drawn along distinctly gendered lines. Such dynamics, on Beauvoir’s view, make authenticity in love impossible – but why?

Simone de Beauvoir spent more time talking about inauthentic love than authentic. But that is because she thought authentic love is so hard to achieve. From the vantage point of 2017, aspects of Beauvoir’s view of authentic love look rather dated and pessimistic: for one thing, it presents men and women in binary terms that are unlikely to resound with many readers. Today’s women have greater access to education and employment than women did in 1949, and may be less likely to see love as life, as Beauvoir charged, instead of a part of life. Although structural inequality persists, relationships between men and women – or men and men, or women and women, etc. – theoretically have better chances of proceeding on an equal footing. But nevertheless many cultural portrayals of love (from Puccini to pop) continue to depict it as a game between unequals – as conquest or domination, seduction or entrapment – where the boundaries are drawn along distinctly gendered lines. Such dynamics, on Beauvoir’s view, make authenticity in love impossible – but why? Today the phrase “debtors’ prison” is often invoked to describe this experience of punitive indebtedness. Sometimes it is meant literally. Consider Melissa Welch-Latronica, a thirty-year-old single mother, who in February was wrenched from her minivan and thrown into a jail cell in Porter County, Illinois, over failure to pay an ambulance bill. Her story is unusual but not unique. A 2018 ACLU

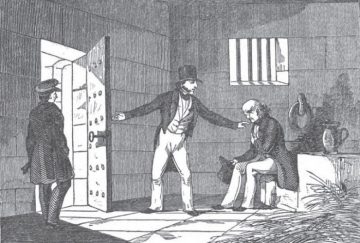

Today the phrase “debtors’ prison” is often invoked to describe this experience of punitive indebtedness. Sometimes it is meant literally. Consider Melissa Welch-Latronica, a thirty-year-old single mother, who in February was wrenched from her minivan and thrown into a jail cell in Porter County, Illinois, over failure to pay an ambulance bill. Her story is unusual but not unique. A 2018 ACLU