Jedediah Britton-Purdy in The New Republic:

John Rawls, who died in 2002, was the most influential American philosopher of the twentieth century. His great work, A Theory of Justice, appeared in 1971 and defined the field of political philosophy for generations. It set out standards for a just society in the form of two principles. First, a just society would protect the strongest set of civil liberties and personal rights compatible with everyone else having the same rights. Second, it would tolerate economic inequalities only if they improved the situation of the poorest and most marginalized (for example, by paying doctors well to encourage people to enter a socially necessary profession).

John Rawls, who died in 2002, was the most influential American philosopher of the twentieth century. His great work, A Theory of Justice, appeared in 1971 and defined the field of political philosophy for generations. It set out standards for a just society in the form of two principles. First, a just society would protect the strongest set of civil liberties and personal rights compatible with everyone else having the same rights. Second, it would tolerate economic inequalities only if they improved the situation of the poorest and most marginalized (for example, by paying doctors well to encourage people to enter a socially necessary profession).

Taken seriously, Rawls’s principles would require a radical transformation: no hedge funds unless allowing them to operate will benefit the homeless? No Silicon Valley IPOs unless they make life better for farmworkers in the Central Valley? A just society would be very different from anything the United States has ever been. Rawls argued that justice would be compatible with either democratic socialism or a “property-owning democracy” of roughly equal smallholders. One thing was clear: America could not remain as it was, on pain of injustice.

It did not remain as it was, but Rawls’s vision did not triumph either. A Theory of Justice was published in 1971, just before economic inequality began its long ascent from its lowest level in history to today’s Second Gilded Age.

More here.

In the lowlands of Bolivia, the most isolated of the Tsimané people live in communities without electricity; they don’t own televisions, computers or phones, and even battery-powered radios are rare. Their minimal exposure to Western culture happens mostly during occasional trips to nearby towns. To the researchers who make their way into Tsimané villages by truck and canoe each summer, that isolation makes the Tsimané an almost uniquely valuable source of insights into the human brain and its processing of music.

In the lowlands of Bolivia, the most isolated of the Tsimané people live in communities without electricity; they don’t own televisions, computers or phones, and even battery-powered radios are rare. Their minimal exposure to Western culture happens mostly during occasional trips to nearby towns. To the researchers who make their way into Tsimané villages by truck and canoe each summer, that isolation makes the Tsimané an almost uniquely valuable source of insights into the human brain and its processing of music. In July 2011, a quiet European capital was shaken by a terrorist car bomb, followed by confused reports suggesting many deaths. When the first news of the murders came through, one small group of online commentators reacted immediately, even though the media had cautiously declined to identify the attackers. They knew at once what had happened – and who was to blame.

In July 2011, a quiet European capital was shaken by a terrorist car bomb, followed by confused reports suggesting many deaths. When the first news of the murders came through, one small group of online commentators reacted immediately, even though the media had cautiously declined to identify the attackers. They knew at once what had happened – and who was to blame. A pair of recent essay collections—Jia Tolentino’s

A pair of recent essay collections—Jia Tolentino’s  In a preface to her ghost stories, Wharton writes, “I do not believe in ghosts, but I am afraid of them.” Following an attack of typhoid as a child, Wharton writes in her autobiography, A Backward Glance, that she returned from the brink of death with “chronic fear” that felt like a “choking agony of terror.” Well into young adulthood, she would not sleep without a light and a maid present in her room. “It was like some dark, indefinable menace, forever dogging my steps, lurking, and threatening,” she writes, and I could not help but think of Hilary Mantel’s childhood encounter with an indescribable evil in her family’s garden. Must all women be visited by terror so consistently and from such a young age? The rumors of paranormal activity at the Mount began after the house become an all-girls school in the forties, and intensified when the theater troupe Shakespeare and Company took residence there in the seventies. The performers were kicked out more than a decade ago in a landlord-tenant dispute that seemed, publicly, not related to the supernatural. Even so, nothing attracts the devil more than a group of adolescent girls, except for maybe a group of actors.

In a preface to her ghost stories, Wharton writes, “I do not believe in ghosts, but I am afraid of them.” Following an attack of typhoid as a child, Wharton writes in her autobiography, A Backward Glance, that she returned from the brink of death with “chronic fear” that felt like a “choking agony of terror.” Well into young adulthood, she would not sleep without a light and a maid present in her room. “It was like some dark, indefinable menace, forever dogging my steps, lurking, and threatening,” she writes, and I could not help but think of Hilary Mantel’s childhood encounter with an indescribable evil in her family’s garden. Must all women be visited by terror so consistently and from such a young age? The rumors of paranormal activity at the Mount began after the house become an all-girls school in the forties, and intensified when the theater troupe Shakespeare and Company took residence there in the seventies. The performers were kicked out more than a decade ago in a landlord-tenant dispute that seemed, publicly, not related to the supernatural. Even so, nothing attracts the devil more than a group of adolescent girls, except for maybe a group of actors. Does the ferocity of the Brexit debate reveal different conceptions of the nature and value of democracy? Brexiteers proudly talk as if the 2016 vote was a rare paradigm of real democracy – “the largest democratic exercise in our history” – while Remainers respond that majority voting by the electorate is only a small part of our democratic system. In a representative democracy, our elected representatives can and should scrutinize the result of an “advisory” referendum as they scrutinize anything else. So why should a referendum result be “respected” if the democratically elected politicians were to decide that, all things considered, it is not in the country’s best interests? On the other hand, Brexiteers will respond that if parliament can overturn the result, what was the point of the referendum in the first place?

Does the ferocity of the Brexit debate reveal different conceptions of the nature and value of democracy? Brexiteers proudly talk as if the 2016 vote was a rare paradigm of real democracy – “the largest democratic exercise in our history” – while Remainers respond that majority voting by the electorate is only a small part of our democratic system. In a representative democracy, our elected representatives can and should scrutinize the result of an “advisory” referendum as they scrutinize anything else. So why should a referendum result be “respected” if the democratically elected politicians were to decide that, all things considered, it is not in the country’s best interests? On the other hand, Brexiteers will respond that if parliament can overturn the result, what was the point of the referendum in the first place? Consider a forest: One notices the trunks, of course, and the canopy. If a few roots project artfully above the soil and fallen leaves, one notices those too, but with little thought for a matrix that may spread as deep and wide as the branches above. Fungi don’t register at all except for a sprinkling of mushrooms; those are regarded in isolation, rather than as the fruiting tips of a vast underground lattice intertwined with those roots. The world beneath the earth is as rich as the one above. For the past two decades, Suzanne Simard, a professor in the Department of Forest & Conservation at the University of British Columbia, has studied that unappreciated underworld. Her specialty is mycorrhizae: the symbiotic unions of fungi and root long known to help plants absorb nutrients from soil. Beginning with landmark experiments describing how carbon flowed between paper birch and Douglas fir trees, Simard found that mycorrhizae didn’t just connect trees to the earth, but to each other as well.

Consider a forest: One notices the trunks, of course, and the canopy. If a few roots project artfully above the soil and fallen leaves, one notices those too, but with little thought for a matrix that may spread as deep and wide as the branches above. Fungi don’t register at all except for a sprinkling of mushrooms; those are regarded in isolation, rather than as the fruiting tips of a vast underground lattice intertwined with those roots. The world beneath the earth is as rich as the one above. For the past two decades, Suzanne Simard, a professor in the Department of Forest & Conservation at the University of British Columbia, has studied that unappreciated underworld. Her specialty is mycorrhizae: the symbiotic unions of fungi and root long known to help plants absorb nutrients from soil. Beginning with landmark experiments describing how carbon flowed between paper birch and Douglas fir trees, Simard found that mycorrhizae didn’t just connect trees to the earth, but to each other as well. Justin E. H. Smith is a professor of history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris. In addition to his recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith is a professor of history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris. In addition to his recent book,  If you could look closely enough at the objects that surround you, zooming in at magnifications far beyond those you could ever see with most microscopes, you would eventually get to a point where the familiar rules of your everyday experiences break down. At scales where blood cells and viruses seem enormous and molecules come into view, things are no longer subject to the simple laws of physics that we learn in high school.

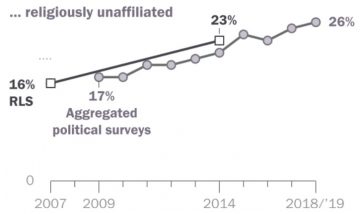

If you could look closely enough at the objects that surround you, zooming in at magnifications far beyond those you could ever see with most microscopes, you would eventually get to a point where the familiar rules of your everyday experiences break down. At scales where blood cells and viruses seem enormous and molecules come into view, things are no longer subject to the simple laws of physics that we learn in high school. The religious landscape of the United States continues to change at a rapid clip. In Pew Research Center telephone surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019, 65% of American adults describe themselves as Christians when asked about their religion, down 12 percentage points over the past decade. Meanwhile, the religiously unaffiliated share of the population, consisting of people who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” now stands at 26%, up from 17% in 2009.

The religious landscape of the United States continues to change at a rapid clip. In Pew Research Center telephone surveys conducted in 2018 and 2019, 65% of American adults describe themselves as Christians when asked about their religion, down 12 percentage points over the past decade. Meanwhile, the religiously unaffiliated share of the population, consisting of people who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” now stands at 26%, up from 17% in 2009. The best thing about this excellent and pleasing anthology of 33 tributes to “Peanuts” is that it will probably evoke your own memories of newspaper comic-strip reading and reawaken your appreciation of Charles M. Schulz’s round-headed, adult-sounding children and the imaginative dog Snoopy. “An isolated four-panel comic strip of Charlie Brown and Linus debating a philosophical point can be appreciated just as it is, humorous, insightful, compact, and perfect; one strip a day documenting one man’s thoughts for half a century has the weight of a full life,” writes the cartoonist Ivan Brunetti. As a collective eulogy to a cultural phenomenon, “The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life” testifies to the inspiration and importance of Schulz’s work at critical times in the authors’ (usually) younger lives. Satirist and critic Joe Queenan reflects: “Unlike so many other venerated objects in U.S. pop culture, it was sweet without being stupid, reassuring without being infantile.”

The best thing about this excellent and pleasing anthology of 33 tributes to “Peanuts” is that it will probably evoke your own memories of newspaper comic-strip reading and reawaken your appreciation of Charles M. Schulz’s round-headed, adult-sounding children and the imaginative dog Snoopy. “An isolated four-panel comic strip of Charlie Brown and Linus debating a philosophical point can be appreciated just as it is, humorous, insightful, compact, and perfect; one strip a day documenting one man’s thoughts for half a century has the weight of a full life,” writes the cartoonist Ivan Brunetti. As a collective eulogy to a cultural phenomenon, “The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life” testifies to the inspiration and importance of Schulz’s work at critical times in the authors’ (usually) younger lives. Satirist and critic Joe Queenan reflects: “Unlike so many other venerated objects in U.S. pop culture, it was sweet without being stupid, reassuring without being infantile.”

I’m writing these words in clothes that reek of tear gas. Trying to process the pulse of the street while still part of it, while our feet are still there on the ground, fleeing water cannons, not knowing where to go, hiding in the crowd, among people just like us, groups of us marching, dodging smoke and soldiers. This is a celebration, a protest, a demand for change that began with students jumping turnstiles in the metro after fares were hiked. Without any organizer, without petitions, leaders, or negotiations, the whole thing escalated and then exploded into chaos in the streets. And there is yelling, and singing, and banging on pots, and fire, and beatings. In front of the palace of La Moneda, near the theater where I work, a man tells a soldier that he doesn’t understand why the soldier is protecting privileges that will never be his. A woman screams that we’re killing ourselves, we’re committing suicide, with all this inequality.

I’m writing these words in clothes that reek of tear gas. Trying to process the pulse of the street while still part of it, while our feet are still there on the ground, fleeing water cannons, not knowing where to go, hiding in the crowd, among people just like us, groups of us marching, dodging smoke and soldiers. This is a celebration, a protest, a demand for change that began with students jumping turnstiles in the metro after fares were hiked. Without any organizer, without petitions, leaders, or negotiations, the whole thing escalated and then exploded into chaos in the streets. And there is yelling, and singing, and banging on pots, and fire, and beatings. In front of the palace of La Moneda, near the theater where I work, a man tells a soldier that he doesn’t understand why the soldier is protecting privileges that will never be his. A woman screams that we’re killing ourselves, we’re committing suicide, with all this inequality. In the autumn of 1869, Charles Darwin was hard at work revising the fifth edition of On The Origin of Species and drafting his next book, The Descent of Man, to be published in 1871. As he finished chapters, Darwin sent them to his daughter, Henrietta, to edit — hoping she could help to head off the hostile responses to his debut, including objections to the implication that morality and ethics could have no basis in nature, because nature had no purpose.

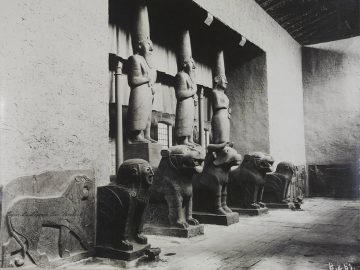

In the autumn of 1869, Charles Darwin was hard at work revising the fifth edition of On The Origin of Species and drafting his next book, The Descent of Man, to be published in 1871. As he finished chapters, Darwin sent them to his daughter, Henrietta, to edit — hoping she could help to head off the hostile responses to his debut, including objections to the implication that morality and ethics could have no basis in nature, because nature had no purpose. When Samuel Beckett visited the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district on 21 December 1936, he had the place to himself. Though King Faisal of Iraq had visited the makeshift museum when it opened six years earlier and the Illustrated London News had run a cover story on the quirky institution, the museum was hardly a popular tourist destination. You had to be in the know. After Beckett rang for the key, he was left alone among colossal lions, scorpion-bird-men, griffons, and sphinxes. “Superbly daemonic, sinister + implacable,” the yet unknown Irish writer wrote in his diary.

When Samuel Beckett visited the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district on 21 December 1936, he had the place to himself. Though King Faisal of Iraq had visited the makeshift museum when it opened six years earlier and the Illustrated London News had run a cover story on the quirky institution, the museum was hardly a popular tourist destination. You had to be in the know. After Beckett rang for the key, he was left alone among colossal lions, scorpion-bird-men, griffons, and sphinxes. “Superbly daemonic, sinister + implacable,” the yet unknown Irish writer wrote in his diary. Late on election night, November 8, 2016, Paul Krugman wrote in the New York Times: “. . . people like me, and probably like most readers of The New York Times, truly didn’t understand the country we live in. We thought that our fellow citizens would not, in the end, vote for a candidate . . . so scary yet ludicrous.” About two and half years before that night, many liberals in India felt something similar at Narendra Modi’s massive victory—though one should say, Modi is scary but not ludicrous.

Late on election night, November 8, 2016, Paul Krugman wrote in the New York Times: “. . . people like me, and probably like most readers of The New York Times, truly didn’t understand the country we live in. We thought that our fellow citizens would not, in the end, vote for a candidate . . . so scary yet ludicrous.” About two and half years before that night, many liberals in India felt something similar at Narendra Modi’s massive victory—though one should say, Modi is scary but not ludicrous.