by Ashutosh Jogalekar

A few days ago I finished watching a new documentary on Bill Gates’ life and work. One of the episodes narrated the sad story of the death of his mother in the mid 1990s from late stage breast cancer. She was a great philanthropist and a doting parent who managed to see Bill get married just before she died. At that point her son was already one of the most successful and wealthiest individuals in the world, but with all his resources and wealth, her life could not be saved. Steve Jobs, another person who had access to every medical treatment that money can buy, died early from cancer. These two stories tell us how great the leveling effect of cancer is, taking poor and rich alike without discrimination. Like war, cancer is the father of us all.

A few days ago I finished watching a new documentary on Bill Gates’ life and work. One of the episodes narrated the sad story of the death of his mother in the mid 1990s from late stage breast cancer. She was a great philanthropist and a doting parent who managed to see Bill get married just before she died. At that point her son was already one of the most successful and wealthiest individuals in the world, but with all his resources and wealth, her life could not be saved. Steve Jobs, another person who had access to every medical treatment that money can buy, died early from cancer. These two stories tell us how great the leveling effect of cancer is, taking poor and rich alike without discrimination. Like war, cancer is the father of us all.

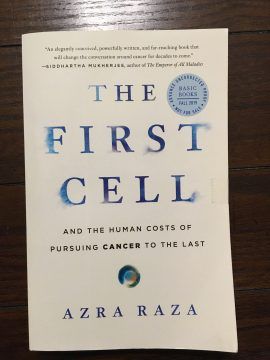

Today breast cancer can be treated much better than it was in the 1990s. There are better drugs and better radiation treatment options available, but for resistant late stage breast cancer the prognosis isn’t much better. In fact, as Dr. Azra Raza who is a distinguished oncologist at Columbia University tells us in this eloquent, thought-provoking and immensely sobering book, what’s true for breast cancer is true for most other kinds of cancer except for a few rare exceptions. The hard hitting truth is that in spite of tens of billions of dollars fueled into research around the world done by some of the smartest people in the field, the truly relevant endpoint for cancer – the increase in someone’s life span – has not changed much even after thirty years. For instance, a study of FDA-approved drugs from 2002 to 2014 showed that these drugs extended people’s lives by an average of only 2 months. Dozens of Nobel Prizes have been given out for basic cancer discoveries, cancer ‘moonshots’ have been promoted by politicians, startups and hospitals working on cancer continue to spend countless dollars and hours on a cure for the disease, but the two things that matter most for patients and their loved ones – extension and quality of life – haven’t changed much.

To know why this depressing scenario persists, Raza offers a simple reason with a hard answer: we are focusing too much on late stage cancer treatment, when the disease has already progressed and spread throughout the body, and much less on early stage detection and prevention. In spite of purported cancer breakthroughs in the media, the treatment is essentially the same as it has been for decades – slash (surgery), poison (chemotherapy) and burn (radiation), a triad of interventions sounding like they have been imported from the Stone Age, used because we can’t use anything better. Read more »

Sometimes, history moves faster than thought. Something like that is happening in the United States in these early days of fall. Though the season is taking longer than normal to turn, the political season has changed more quickly than anyone expected. The opinions of last week – such as the long article I had written for 3QD on the prospects of Donald Trump and the Democrats in 2020 – have suddenly become irrelevant, and I find myself writing this wholly surprising piece on the possible impeachment of Donald Trump. As these lines are being written, 223 Democrats and one Independent in the US House of Representatives – a clear majority –

Sometimes, history moves faster than thought. Something like that is happening in the United States in these early days of fall. Though the season is taking longer than normal to turn, the political season has changed more quickly than anyone expected. The opinions of last week – such as the long article I had written for 3QD on the prospects of Donald Trump and the Democrats in 2020 – have suddenly become irrelevant, and I find myself writing this wholly surprising piece on the possible impeachment of Donald Trump. As these lines are being written, 223 Democrats and one Independent in the US House of Representatives – a clear majority –

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

I remember the first time I thought I might be able to get on board with Stoicism. I read a

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Do you remember when the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw suggested significant changes to English spelling so that it would make more sense? Probably not, because it was more than 70 years ago. According to him

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

Things are changing. Always, everywhere, immensely and minutely, the history of mankind unfolds as we rotate around a grand burning star (also, everything everywhere else changes; the history of mankind may be of the least consequence on a cosmic scale, but I digress). I digress too early; I include parentheticals too soon; I stall with flowery descriptions of the sun. Because – ugh – I’m going to talk about “how divided we are as a nation.” It’s such a tired phrase; I don’t want to write about it. It’s stale because it’s static, and anyway, the declaration is often accompanied by divisive rhetoric. Wherever one may fall on the political spectrum (and here I’m being gracious; how often do we now identify with a “side”), they likely have established opinions of those who lie elsewhere. It does seem increasingly difficult to imagine a sweeping reconciliation when we continue to pour our definitions in concrete and defend our positions by reason of consistency. Inflexibility begets inability to listen, and thus to understand, which is why we find our differences so baffling and allow our prejudices to influence our opinions. So, finally, here it is: my own personal take on how we can get people to stop saying how divided we are. Bear with me, because I’m going to try and sell contradictions as potential energy for unity.

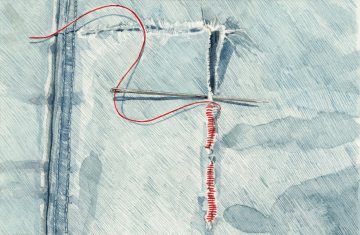

Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he

Several years ago, while living in London, England, my wife met Prince Charles at an event associated with the Prince’s Foundation, where she worked. She returned with two observations: First, the Prince of Wales used two fingers – index and middle – when he pointed. Second, Charles’s suit had visible signs of mending. A Google search fails to substantiate the double-barrelled gesture, but the Prince’s penchant for patching has been well documented. Last year, the journalist Marion Hume discovered a cardboard box containing more than 30 years of off-cuts and leftover materials from the Prince’s suits, tucked away in a corner at his Savile Row tailor, Anderson & Sheppard. “I have always believed in trying to keep as many of my clothes and shoes going for as long as possible … through patches and repairs,” he  Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth.

Self-replicating, bacterial life first appeared on Earth about 4 billion years ago. For most of Earth’s history, life remained at the single-celled level, and nothing like a nervous system existed until around 600 or 700 million years ago (MYA). In the attention schema theory, consciousness depends on the nervous system processing information in a specific way. The key to the theory, and I suspect the key to any advanced intelligence, is attention—the ability of the brain to focus its limited resources on a restricted piece of the world at any one time in order to process it in greater depth. The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.”

The crowded room was awaiting one word: “Fire.” Nearly two decades before Boeing’s MCAS system crashed two of the plane-maker’s brand-new 737 MAX jets, Stan Sorscher knew his company’s increasingly toxic mode of operating would create a disaster of some kind. A long and proud “safety culture” was rapidly being replaced, he argued, with “a culture of financial bullshit, a culture of groupthink.”

Nearly two decades before Boeing’s MCAS system crashed two of the plane-maker’s brand-new 737 MAX jets, Stan Sorscher knew his company’s increasingly toxic mode of operating would create a disaster of some kind. A long and proud “safety culture” was rapidly being replaced, he argued, with “a culture of financial bullshit, a culture of groupthink.” To experience a thing

To experience a thing Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them.

Capitalism reigns. But capitalism is in trouble. Therein lies the paradox of our age. For the first time in human history, a single economic system spans the globe. Of course there are differences between capitalism Chinese-style, American-style and Swedish-style. Close up, these differences can seem significant. But viewed through a wider lens, the distinctions blur. As the economist Branco Milanovic writes in his new book, Capitalism Alone, “the entire globe now operates according to the same economic principles – production organized for profit using legally free wage labor and mostly privately owned capital, with decentralized coordination”. After the fall of Soviet communism in 1989, and China’s embrace of the market, crowned by the nation’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, it seemed, for a brief flicker of human history, that the world was converging on a political economy of free markets in liberal democracies. As it turned out, markets spread, but without necessarily bringing more democracy or liberalism along with them.