Robert Talisse in Liberal Currents:

The Democrats are presently courting electoral disaster. Not only is the field of those seeking the Party’s 2020 nomination heavily populated and expanding by the week, but those already in the ring, each with their own strengths and weaknesses, seem to be configured in what former President Obama recently described as a “circular firing squad,” each poised to pull the trigger on some particular opponent. The worry is that, once the smoke dissipates, every plausible nominee will have been mortally wounded in the internecine battle. A greater political gift to the Republicans could hardly be imagined.

Thus the 2020 Democratic Convention will be fraught by the same Catch-22 that plagued its predecessor. If the Party nominates one of its old guard stalwarts, it will be seen as a political machine that mindlessly manufactures “politics as usual.” This will dampen support among younger, more progressive voters. However, nominating an especially progressive candidate carries the risk of alienating older, middle-of-the-road Democrats, who happen also to belong to the demographic that is most likely to turn out on Election Day. Thus the Democrats’ dilemma: A standard-issue nominee nearly ensures a progressive third-party spoiler, driven by the contention that the DNC is hopelessly rigged in favor of milquetoast careerists over visionary change-makers. But nominating a left-progressive candidate will depress Democratic votes in electorally crucial non-coastal states.

More here.

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an

A moonshot is on the rise on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda. At last month’s meeting of the National Space Council in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence laid out an  There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face.

There’s a scene early on in the French documentary Salafistes (“Jihadists”) where the camera spans over a throng of people gathered in a village in northern Mali: the crowd is there to watch as the “Islamic Police” cut off a 25-year-old man’s hand. The shot zooms in as the young man, tethered in ropes around a chair, slumps over, unconscious, while his hand is sawed off with a small, serrated blade. Young boys in the background howl incoherently. In the next scene, the same young man is filmed lying in a bed cocooned by a lime green mosquito net, his severed limb wrapped in thick white bandages. “This is the application of sharia,” he tells the camera. “I committed a theft; in accordance with sharia my hand was amputated. Once I recover I will be purified and all my sins erased.” The trace of a drugged smile lingers across his face. I

I The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse.

The explosion on April 26, 1986, at the V.I. Lenin, or Chernobyl, Atomic Energy Station in what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic is thought to have “vaporized” one worker on the spot. Another 30, drenched in fatal doses of radiation, died gruesome, lingering deaths. As of 2005, as many as 5,000 additional cancer deaths were projected locally — among 25,000 extra cancer cases Europe-wide. Contamination rendered 1,838-plus square miles “uninhabitable.” And a spectral column of radioactive gases escaped into the atmosphere, setting people on edge from Stockholm to San Francisco. It was the worst nuclear accident in history and could have been far worse. Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past.

Gdańsk was a city of the borders for many years, with a prevailing influence of German culture, German music, German language, because even the Polish proletariat when they came from the villages were Germanized, because with the German language they had better chances. But there used to be about 15%-20% Polish speaking people, 3% French people, 2% English people, 3.5% Russians, Scottish people as well, a lot of Dutch people; this was a typical city of the borders. This was over after the Polish partition of 1795. And then Gdańsk, which used to be a rich merchant city, a merchant emporium, became a provincial Prussian city. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these were periods of the great German nationalisms, which end up with the crime of 1939, because most of the Polish people here were murdered at that time. Surprisingly, the Jews could leave. Because this used to be the Free City of Gdańsk, the so-called ‘Free City’, and the authorities of Gdańsk signed an agreement with the Jewish Community in 1939, more or less, perhaps one year earlier, and while the war was still going on, until 1940 the Jewish population was still leaving. So, the multicultural city was over with the Prussian partition. Then, after the war, 99% of the German population left, and Polish people from various parts of former Poland came, from burned-down Warsaw, from Wilno, or from the Eastern borders, from those parts; so, people only came back to the idea of multiculturalism, after 1989, with the end of Communism. But, if ever we speak of multiculturalism in Gdańsk, we speak of the distant past. Of course, it’s a very good example of something to reach for, but it’s a deep past. As we await the final season of

As we await the final season of  These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God

These days, no less an authority than Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, said recently that God

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

In Prophet of Freedom, Blight allows us to experience both the exuberance and the difficulties of a life acted out on stages. We see Douglass, as a small boy, gathering damp pages from a discarded Bible out of the gutter so he could learn how to read. We are shown the young, proud orator being shunted into filthy, segregated train cars even as he traveled to address throngs of adoring fans. And we are at the Rochester train station to see his wife Anna rush to meet him with a bundle of freshly ironed shirts before returning to her job making shoes, or caring for their five children, while the abolitionist rock star continued on his way. We are with him near the end of his life when he climbed a rocky crag near the Acropolis and lingered there to read St. Paul’s famous “Address to the Athenians,” in which the Apostle declared all people to be the “offspring” of God and that God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth.”

Eighty percent of women living in communist East Germany always reached orgasm during sex, according to the Hamburg magazine Neue Revue in 1990. For West German women that figure was only 63 percent. Those counterintuitive findings confirmed two earlier studies, which East German sex researchers had published in 1984 and 1988. Those had found East German women reported high levels of sexual satisfaction outpacing those in the West.

Eighty percent of women living in communist East Germany always reached orgasm during sex, according to the Hamburg magazine Neue Revue in 1990. For West German women that figure was only 63 percent. Those counterintuitive findings confirmed two earlier studies, which East German sex researchers had published in 1984 and 1988. Those had found East German women reported high levels of sexual satisfaction outpacing those in the West. Hayden White, the philosopher of history whose classic Metahistory (1973) has had an enduring influence on the humanities, died last year. In a career spanning half a century, White, whose appointments included Stanford University and the University of California at Santa Cruz, provoked, alarmed, and invigorated professional historians and lay readers alike. In Metahistory and elsewhere,

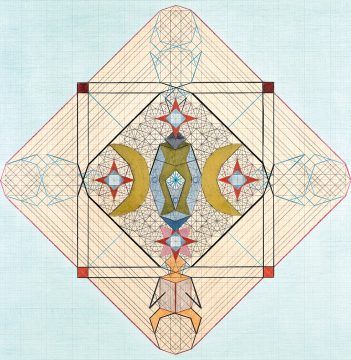

Hayden White, the philosopher of history whose classic Metahistory (1973) has had an enduring influence on the humanities, died last year. In a career spanning half a century, White, whose appointments included Stanford University and the University of California at Santa Cruz, provoked, alarmed, and invigorated professional historians and lay readers alike. In Metahistory and elsewhere,  Few people ever observed Emma Kunz, a Swiss alternative healer and artist, at work. One of the only accounts comes from a man called Anton Meier, who first met Kunz when his parents asked her to cure his childhood polio. Kunz was a spiritualist who used drawing as a way to divine the future. Meier recalled watching her in the early 1940s as she attempted to predict the outcome of a meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

Few people ever observed Emma Kunz, a Swiss alternative healer and artist, at work. One of the only accounts comes from a man called Anton Meier, who first met Kunz when his parents asked her to cure his childhood polio. Kunz was a spiritualist who used drawing as a way to divine the future. Meier recalled watching her in the early 1940s as she attempted to predict the outcome of a meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt: We left our E-Z Pass in the apartment. Stacy and I realize this only upon arriving at the mouth of the tunnel en route to the Weill Cornell ER. The gate fails to lift as we approach and we almost plow through it. The man at the tollbooth tries to reckon with us, incoherent and hysterical and blocking traffic.

We left our E-Z Pass in the apartment. Stacy and I realize this only upon arriving at the mouth of the tunnel en route to the Weill Cornell ER. The gate fails to lift as we approach and we almost plow through it. The man at the tollbooth tries to reckon with us, incoherent and hysterical and blocking traffic.

“This is actually one of the most surprising things in the whole history of public opinion,” says

“This is actually one of the most surprising things in the whole history of public opinion,” says