by Samia Altaf

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

Farzana, a young woman from a lower-middle-class family, had married a man against her family’s wishes. She had come to the High Court that day to provide proof that she had married voluntarily and had not been abducted by her husband as her family claimed when they filed the case to “get her back.” Farzana was dead, the bridal henna still bright red on her hands and feet, before her case was called for hearing by the court.

Though this was one in a string of incidents of violence against women, and though many similar incidents have happened in Pakistan since, the shock and horror of the murder consumed us for a few days and became international news. On May 29, 2014, the BBC asked, “How can families do this?”

One answer to the question is that families can perpetrate violence against their daughters because they have years of practice doing so every day. Women in Pakistan live in a culture of ambient violence, and incidents of exaggerated violence labeled “honor killings” are just lamentable spikes in the ambient violence of their everyday lives. Read more »

Australia has had an outsized influence on philosophy, especially in the middle and late-20th century. The field still shows a broad Australian footprint. For many years, Princeton University in New Jersey, perennially one of the highest-ranked philosophy departments, has had three or four Australians on its faculty (depending on when you look and on how you count Australians). Princeton has always been an especially clear case, but the influence is all over, an ongoing export of both people and ideas. Given the modest size of Australia (with a population of about 25 million now, but under 17 million until the end of the 1980s), and the popular image of the country’s intellectual life, this is a bit surprising. What is going on? How did this happen?

Australia has had an outsized influence on philosophy, especially in the middle and late-20th century. The field still shows a broad Australian footprint. For many years, Princeton University in New Jersey, perennially one of the highest-ranked philosophy departments, has had three or four Australians on its faculty (depending on when you look and on how you count Australians). Princeton has always been an especially clear case, but the influence is all over, an ongoing export of both people and ideas. Given the modest size of Australia (with a population of about 25 million now, but under 17 million until the end of the 1980s), and the popular image of the country’s intellectual life, this is a bit surprising. What is going on? How did this happen? Cynthia Haven: Violence has been a theme of this conference: Juan Gabriel Vásquez on the Colombian drug wars, three sessions for the Nigerian journalist and author Helon Habila, who spoke about the kidnapped Boko Haram girls and the ongoing terrorism in Nigeria—even the French writer and critic Raphaëlle Leyris from Le Monde noted that several books a month are still coming out on the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris. And today’s session on literature and evil. You, too, have written about unspeakable violence going on in the middle of Europe, at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Several have commented in Bergen on how the cataclysms of mid-century Europe seem to be revisiting us today, and they wish they could shake that feeling.

Cynthia Haven: Violence has been a theme of this conference: Juan Gabriel Vásquez on the Colombian drug wars, three sessions for the Nigerian journalist and author Helon Habila, who spoke about the kidnapped Boko Haram girls and the ongoing terrorism in Nigeria—even the French writer and critic Raphaëlle Leyris from Le Monde noted that several books a month are still coming out on the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris. And today’s session on literature and evil. You, too, have written about unspeakable violence going on in the middle of Europe, at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Several have commented in Bergen on how the cataclysms of mid-century Europe seem to be revisiting us today, and they wish they could shake that feeling. Psychologists have lots of evidence that implicit social biases—our unconscious, knee-jerk attitudes associated with specific races, sexes and other categories—are widespread, and many assumed they do not evolve. The feelings are just too deep. But a new study finds that over roughly the past decade, both implicit and explicit, or conscious, attitudes toward several social groups have grown warmer.

Psychologists have lots of evidence that implicit social biases—our unconscious, knee-jerk attitudes associated with specific races, sexes and other categories—are widespread, and many assumed they do not evolve. The feelings are just too deep. But a new study finds that over roughly the past decade, both implicit and explicit, or conscious, attitudes toward several social groups have grown warmer. As young people rightly demand real solutions to climate change, the question is not what to do — eliminate fossil fuels by 2050 — but how. Beyond decarbonizing today’s electric grid, we must use clean electricity to replace fossil fuels in transportation, industry and heating. We must provide for the fast-growing energy needs of poorer countries and extend the grid to a billion people who now lack electricity. And still more electricity will be needed to remove excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by midcentury.

As young people rightly demand real solutions to climate change, the question is not what to do — eliminate fossil fuels by 2050 — but how. Beyond decarbonizing today’s electric grid, we must use clean electricity to replace fossil fuels in transportation, industry and heating. We must provide for the fast-growing energy needs of poorer countries and extend the grid to a billion people who now lack electricity. And still more electricity will be needed to remove excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by midcentury. The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’.

The light is dim, the air richly scented. Little purple tea lights flicker in the votive candle rack and the walls are decorated with twining sunflowers, exuberant passionflowers and several canvases of blousy green carnations monogrammed with Oscar Wilde’s prisoner ID number C.3.3. The Temple is a deconsecrated church with an attractive dark wood ceiling and matching antique chairs. A half-size marble statue of Wilde presides. The artists, McDermott and McGough, have painted various icons spelling out pejoratives such as ‘pansy’, ‘faggot’ and ‘cocksucker’, adorned with gold leaf and richly-coloured paint. Towards the back are intricate woodcut-style depictions of massacres with titles like ‘Nun Cutting Rope of Dead Homeric’, black canvases with cut-out fatality statistics, and monochrome portraits of individuals more recently killed by homophobia and transphobia, such as Justin Fashanu, Brandon Teena and Marsha P. Johnson. A placard in the hallway spells out all of the bigotries the temple stands against, ending with the instruction ‘only love here’. Opposite is a purpose-built offertory box ‘For the Sons and Daughters of Oscar Wilde’. In 1651, Thomas Hobbes famously wrote that life in the state of nature – that is, our natural condition outside the authority of a political state – is ‘solitary, poore, nasty brutish, and short.’ Just over a century later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau countered that human nature is essentially good, and that we could have lived peaceful and happy lives well before the development of anything like the modern state. At first glance, then, Hobbes and Rousseau represent opposing poles in answer to one of the age-old questions of human nature: are we naturally good or evil? In fact, their actual positions are both more complicated and interesting than this stark dichotomy suggests. But why, if at all, should we even think about human nature in these terms, and what can returning to this philosophical debate tell us about how to evaluate the political world we inhabit today?

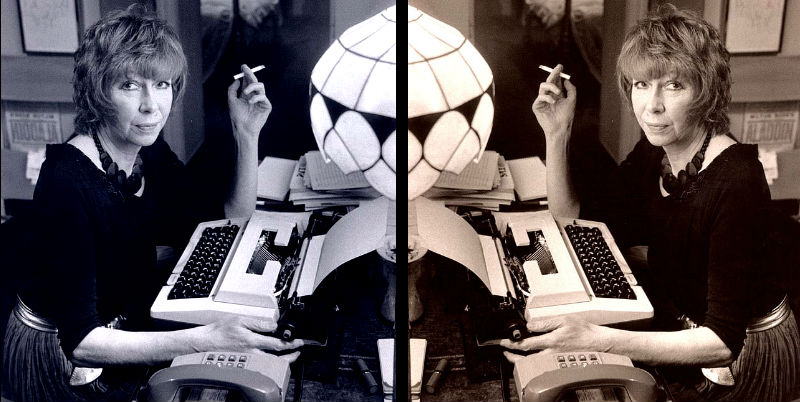

In 1651, Thomas Hobbes famously wrote that life in the state of nature – that is, our natural condition outside the authority of a political state – is ‘solitary, poore, nasty brutish, and short.’ Just over a century later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau countered that human nature is essentially good, and that we could have lived peaceful and happy lives well before the development of anything like the modern state. At first glance, then, Hobbes and Rousseau represent opposing poles in answer to one of the age-old questions of human nature: are we naturally good or evil? In fact, their actual positions are both more complicated and interesting than this stark dichotomy suggests. But why, if at all, should we even think about human nature in these terms, and what can returning to this philosophical debate tell us about how to evaluate the political world we inhabit today? Sandy Fawkes landed in Atlanta on the night of November 7, 1974. She’d spent the day in Washington on a fruitless quest to interview former Vice President Spiro Agnew, part of a one-month tryout with an American weekly newspaper that paid her extraordinarily well, including travel and hotel—far more than her usual employer, the Daily Express, could afford thanks to the country’s current economic crisis.

Sandy Fawkes landed in Atlanta on the night of November 7, 1974. She’d spent the day in Washington on a fruitless quest to interview former Vice President Spiro Agnew, part of a one-month tryout with an American weekly newspaper that paid her extraordinarily well, including travel and hotel—far more than her usual employer, the Daily Express, could afford thanks to the country’s current economic crisis. In

In  The debate over the effects of artificial intelligence has been dominated by two themes. One is the fear of a

The debate over the effects of artificial intelligence has been dominated by two themes. One is the fear of a  A

A María Sonia Cristoff has often recounted one of her formative reading experiences. Hired to translate the diaries of Thomas Bridges—a nineteenth-century Anglican missionary in Argentina—she traveled from Buenos Aires to his family’s farm outside of Ushaia, which sits at the southern edge of Patagonia in the Tierra del Fuego province. There she was given a room with a window overlooking the Beagle Channel and a stack of papers with a pencil mark indicating where she should begin. She lacked any access to the rest of the diary since Bridges’ heirs, insisting on a neutral voice for the new rendering of his work, replaced translators every two months, assigning each one a single section of the work.

María Sonia Cristoff has often recounted one of her formative reading experiences. Hired to translate the diaries of Thomas Bridges—a nineteenth-century Anglican missionary in Argentina—she traveled from Buenos Aires to his family’s farm outside of Ushaia, which sits at the southern edge of Patagonia in the Tierra del Fuego province. There she was given a room with a window overlooking the Beagle Channel and a stack of papers with a pencil mark indicating where she should begin. She lacked any access to the rest of the diary since Bridges’ heirs, insisting on a neutral voice for the new rendering of his work, replaced translators every two months, assigning each one a single section of the work. I’ve chosen the fox as a symbolic representation of a writer. The fox is rich with meaning. In the Western cultural tradition, the fox is mainly a male creature. In Eastern cultures, the fox is mostly a female creature. In Slavic folk culture, the fox is also predominantly female. The fox is not a superior creature: she is a loser and a loner, wild and vulnerable. The fox is one of the most popular hunting targets: her skin, her fur, has a commercial value, a detail which makes the fox a deeply tragic figure. The fox is betrayed more often then it betrays. Representations of the fox differ from culture to culture. I was raised on the fox’s representation in Aesop’s fables and Western European medieval novels. In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese mythology, the fox is a semi-divine creature, a god’s messenger, a demonic shape-shifter that passes the borders between realms—human, animal, demonic. The fox is also seen as a cheap entertainer, a liar, a cheater, a little thief with a risky appetite for the “metaphysical bite,” a thief with a constant desire to grab a “heavenly chicken.”

I’ve chosen the fox as a symbolic representation of a writer. The fox is rich with meaning. In the Western cultural tradition, the fox is mainly a male creature. In Eastern cultures, the fox is mostly a female creature. In Slavic folk culture, the fox is also predominantly female. The fox is not a superior creature: she is a loser and a loner, wild and vulnerable. The fox is one of the most popular hunting targets: her skin, her fur, has a commercial value, a detail which makes the fox a deeply tragic figure. The fox is betrayed more often then it betrays. Representations of the fox differ from culture to culture. I was raised on the fox’s representation in Aesop’s fables and Western European medieval novels. In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese mythology, the fox is a semi-divine creature, a god’s messenger, a demonic shape-shifter that passes the borders between realms—human, animal, demonic. The fox is also seen as a cheap entertainer, a liar, a cheater, a little thief with a risky appetite for the “metaphysical bite,” a thief with a constant desire to grab a “heavenly chicken.” Sources from late antiquity, such as the 5th-century CE Christian writers Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Cyril of Alexandria, state that Socrates was, at least as a younger man, a lover of both sexes. They corroborate occasional glimpses of an earthy Socrates in Plato’s own writings, such as in the dialogue Charmides where Socrates claims to be intensely aroused by the sight of a young man’s bare chest. However, the only partner of Socrates’ whom Plato names is Xanthippe; but since she was carrying a baby in her arms when Socrates was aged 70, it is unlikely they met more than a decade or so earlier, when Socrates was already in his 50s. Plato’s failure to mention the earlier aristocratic wife Myrto might be an attempt to minimise any perception that Socrates came from a relatively wealthy background with connections to high-ranking members of his community; it was largely because Socrates was believed to be associated with the antidemocratic aristocrats who took power in Athens that he was put on trial and executed in 399 BCE.

Sources from late antiquity, such as the 5th-century CE Christian writers Theodoret of Cyrrhus and Cyril of Alexandria, state that Socrates was, at least as a younger man, a lover of both sexes. They corroborate occasional glimpses of an earthy Socrates in Plato’s own writings, such as in the dialogue Charmides where Socrates claims to be intensely aroused by the sight of a young man’s bare chest. However, the only partner of Socrates’ whom Plato names is Xanthippe; but since she was carrying a baby in her arms when Socrates was aged 70, it is unlikely they met more than a decade or so earlier, when Socrates was already in his 50s. Plato’s failure to mention the earlier aristocratic wife Myrto might be an attempt to minimise any perception that Socrates came from a relatively wealthy background with connections to high-ranking members of his community; it was largely because Socrates was believed to be associated with the antidemocratic aristocrats who took power in Athens that he was put on trial and executed in 399 BCE. “Lost and Wanted” is a novel of female friendship without the furious intimacy of, say, Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. It’s a novel about female friendship begun in America in the 1990s, when women didn’t talk about sexual harassment and friends didn’t talk about race. When women (and especially women of color) were trying to build careers for themselves and no one was acknowledging how much harder it would be for them than it would be for white men in their position, and trying to do so while having children, either with partners or on their own, and trying to balance all of that striving without ever giving anyone reason to believe that they were more emotional or less stable than any of their peers.

“Lost and Wanted” is a novel of female friendship without the furious intimacy of, say, Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. It’s a novel about female friendship begun in America in the 1990s, when women didn’t talk about sexual harassment and friends didn’t talk about race. When women (and especially women of color) were trying to build careers for themselves and no one was acknowledging how much harder it would be for them than it would be for white men in their position, and trying to do so while having children, either with partners or on their own, and trying to balance all of that striving without ever giving anyone reason to believe that they were more emotional or less stable than any of their peers.