Derek Thompson in The Atlantic:

In his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted a 15-hour workweek in the 21st century, creating the equivalent of a five-day weekend. “For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem,” Keynes wrote, “how to occupy the leisure.”

This became a popular view. In a 1957 article in The New York Times, the writer Erik Barnouw predicted that, as work became easier, our identity would be defined by our hobbies, or our family life. “The increasingly automatic nature of many jobs, coupled with the shortening work week [leads] an increasing number of workers to look not to work but to leisure for satisfaction, meaning, expression,” he wrote.

These post-work predictions weren’t entirely wrong. By some counts, Americans work much less than they used to. The average work year has shrunk by more than 200 hours. But those figures don’t tell the whole story. Rich, college-educated people—especially men—work more than they did many decades ago. They are reared from their teenage years to make their passion their career and, if they don’t have a calling, told not to yield until they find one.

The economists of the early 20th century did not foresee that work might evolve from a means of material production to a means of identity production. They failed to anticipate that, for the poor and middle class, work would remain a necessity; but for the college-educated elite, it would morph into a kind of religion, promising identity, transcendence, and community. Call it workism.

More here.

Everything we think about the world outside our immediate senses is shaped by information brought to us by other sources. In the case of what’s currently happening to the human race, we call that information “the news.” There is no such thing as “unfiltered” news — no matter how we get it, someone is deciding what information to convey and how to convey it. And the way that is happening is currently in a state of flux. Today’s guest, journalist Jessica Yellin, has seen the news business from the perspective of both the establishment and the upstart. Working for major news organizations, she witnessed the strange ways in which decisions about what to cover were made, including the constant focus on short-term profits. And now she is spearheading a new online effort to bring people news in a different way. We talk about what the news business is, what it should be, and where it is going.

Everything we think about the world outside our immediate senses is shaped by information brought to us by other sources. In the case of what’s currently happening to the human race, we call that information “the news.” There is no such thing as “unfiltered” news — no matter how we get it, someone is deciding what information to convey and how to convey it. And the way that is happening is currently in a state of flux. Today’s guest, journalist Jessica Yellin, has seen the news business from the perspective of both the establishment and the upstart. Working for major news organizations, she witnessed the strange ways in which decisions about what to cover were made, including the constant focus on short-term profits. And now she is spearheading a new online effort to bring people news in a different way. We talk about what the news business is, what it should be, and where it is going. It takes a special sort of person to be a cardiologist. This is not always a good thing.

It takes a special sort of person to be a cardiologist. This is not always a good thing. It has long been claimed that there are somewhere between three and 36 basic plots in all forms of storytelling. Three years ago, academics fed nearly 2,000 stories into a computer analysis and concluded that there were

It has long been claimed that there are somewhere between three and 36 basic plots in all forms of storytelling. Three years ago, academics fed nearly 2,000 stories into a computer analysis and concluded that there were

There are at least two Diderots, both controversial, both remarkable Enlightenment figures. The first was a renowned philosophe and atheist associated with Voltaire and Rousseau but often thought their inferior in accomplishment. He was known chiefly as the major author and editor of the

There are at least two Diderots, both controversial, both remarkable Enlightenment figures. The first was a renowned philosophe and atheist associated with Voltaire and Rousseau but often thought their inferior in accomplishment. He was known chiefly as the major author and editor of the  Why do we so often believe that secrecy must necessarily mask transgression? Busch unravels that association in How to Disappear. The laborious, sometimes caustic recipes for invisibility ink and potion included in the book (some from mythology, some from military history) themselves suggest something nefarious. Take for instance the hulinhjalmur, an invisibility-granting symbol from ancient Iceland that had to be smeared on a person’s forehead with a mixture of “blood drawn from your finger and nipples, mixed with the blood and brains of a raven along with a piece of human stomach.” Busch writes that our tendency “to associate [invisibility] with wrongdoing, degeneracy, malice, even the work of the devil” is not accidental. It is inscribed into many of our oldest myths, including the Ring of Gyges, retold famously by Kristin Scott Thomas’s character in The English Patient. Gyges, a simple shepherd who discovers a ring that confers invisibility, uses his newfound power to kill the king, marry his wife, and take the throne for himself. This idea, that invisibility can lead “an otherwise ordinary and honorable person to commit transgressions and behave unjustly,” has stubbornly stayed with us.

Why do we so often believe that secrecy must necessarily mask transgression? Busch unravels that association in How to Disappear. The laborious, sometimes caustic recipes for invisibility ink and potion included in the book (some from mythology, some from military history) themselves suggest something nefarious. Take for instance the hulinhjalmur, an invisibility-granting symbol from ancient Iceland that had to be smeared on a person’s forehead with a mixture of “blood drawn from your finger and nipples, mixed with the blood and brains of a raven along with a piece of human stomach.” Busch writes that our tendency “to associate [invisibility] with wrongdoing, degeneracy, malice, even the work of the devil” is not accidental. It is inscribed into many of our oldest myths, including the Ring of Gyges, retold famously by Kristin Scott Thomas’s character in The English Patient. Gyges, a simple shepherd who discovers a ring that confers invisibility, uses his newfound power to kill the king, marry his wife, and take the throne for himself. This idea, that invisibility can lead “an otherwise ordinary and honorable person to commit transgressions and behave unjustly,” has stubbornly stayed with us. In the Indian and Islamic cultures, then, we have what should be uncontroversial examples of sophisticated and long-lasting philosophical traditions. Then there is the culture dearest to Van Norden’s own heart, namely that of China; Baggini also devotes much attention to this, as well as to Japanese philosophy. Though these traditions are arguably not quite as given to the kind of scholastic, dialectical debates so beloved of Indian, Islamic and contemporary analytic philosophers, it seems pretty uncontentious that there is philosophical material here too, notably in the field of ethics with Confucianism and its critics. More open to debate would be the case of various “indigenous” cultures around the world. Neither of our authors ventures far in this direction, though both are optimistic that it would be rewarding to approach traditional African cultures, say, as a repository of philosophical insight. Distinctive methodological challenges arise here, since for indigenous African societies we largely lack traditions of argumentative writing. Work on African philosophy has instead drawn mostly on living oral traditions and on the studies of ethnographers, anthropologists and archaeologists. Similar issues are raised by, among others, Native American, Inuit and Australian aboriginal cultures, and further back in history, ancient Mesoamerica. All of these have, to varying degrees, been subjected to philosophical analysis. For example there is a substantial literature on African conceptions of the person, and on the causal theories underlying the wide range of healing practices found in traditional African societies. Then too, the very notion of locating philosophy in an oral tradition rather than in the writings of brilliant individuals is itself an intriguing one.

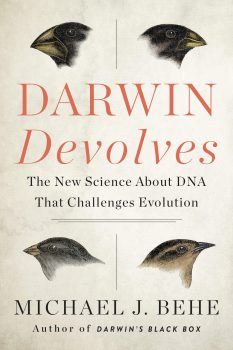

In the Indian and Islamic cultures, then, we have what should be uncontroversial examples of sophisticated and long-lasting philosophical traditions. Then there is the culture dearest to Van Norden’s own heart, namely that of China; Baggini also devotes much attention to this, as well as to Japanese philosophy. Though these traditions are arguably not quite as given to the kind of scholastic, dialectical debates so beloved of Indian, Islamic and contemporary analytic philosophers, it seems pretty uncontentious that there is philosophical material here too, notably in the field of ethics with Confucianism and its critics. More open to debate would be the case of various “indigenous” cultures around the world. Neither of our authors ventures far in this direction, though both are optimistic that it would be rewarding to approach traditional African cultures, say, as a repository of philosophical insight. Distinctive methodological challenges arise here, since for indigenous African societies we largely lack traditions of argumentative writing. Work on African philosophy has instead drawn mostly on living oral traditions and on the studies of ethnographers, anthropologists and archaeologists. Similar issues are raised by, among others, Native American, Inuit and Australian aboriginal cultures, and further back in history, ancient Mesoamerica. All of these have, to varying degrees, been subjected to philosophical analysis. For example there is a substantial literature on African conceptions of the person, and on the causal theories underlying the wide range of healing practices found in traditional African societies. Then too, the very notion of locating philosophy in an oral tradition rather than in the writings of brilliant individuals is itself an intriguing one. “[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,

“[T]here is in fact nothing that can alleviate that fatal flaw in Darwinism” says Professor Behe,  rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.”

rapture, claiming that “Michael Behe’s Darwin Devolves Topples Foundational Claim of Evolutionary Theory” and that “Anyone interested in knowing the truth about the design/evolution debate will find Darwin Devolves a must read.” I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he

I wonder whether Behe’s most vociferous supporters actually understand his position. Unlike them, he

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.

I was lugging several superheavy boxes of dishes up the concrete stairs from the sidewalk to the front door when a guy in a silver suit materialized in front of me. The first rule of moving is that when you pick something up, you don’t put it down until you have it where it goes. This is because picking it up and putting it down are half the battle. So, I tried to go around him.