Matt Wilstein in Daily Beast:

“There’s a question I get asked a lot,” Jimmy Kimmel said at the beginning of a recent monologue. “Now that we have this president, people ask, ‘Is it easy now? It must be easy to write jokes, there’s so much material, the jokes must write themselves.’ And it’s not true. We still write the jokes ourselves. And in fact, in a way, it makes it harder to be funny when nonsense and stupidity is pouring on your head at all times.” Kimmel’s comments were merely a set-up to explain that his jokes didn’t write themselves “until today, when Kanye West visited the White House.” But aside from those rare instances, his sentiment echoes what several late-night hosts have expressed during the first two years of the Trump presidency. And especially in 2018, it seemed, the late-night men and still-too-few women frequently struggled to find the best ways to joke about this president and the madness that surrounds him. The daily onslaught of crazy from the White House, combined with a viewing public increasingly eager to call out any perceived transgression on social media, led to an unprecedented level of outrage, often of the “faux” variety. Here, in chronological order, are the most controversial late-night clips of 2018.

“There’s a question I get asked a lot,” Jimmy Kimmel said at the beginning of a recent monologue. “Now that we have this president, people ask, ‘Is it easy now? It must be easy to write jokes, there’s so much material, the jokes must write themselves.’ And it’s not true. We still write the jokes ourselves. And in fact, in a way, it makes it harder to be funny when nonsense and stupidity is pouring on your head at all times.” Kimmel’s comments were merely a set-up to explain that his jokes didn’t write themselves “until today, when Kanye West visited the White House.” But aside from those rare instances, his sentiment echoes what several late-night hosts have expressed during the first two years of the Trump presidency. And especially in 2018, it seemed, the late-night men and still-too-few women frequently struggled to find the best ways to joke about this president and the madness that surrounds him. The daily onslaught of crazy from the White House, combined with a viewing public increasingly eager to call out any perceived transgression on social media, led to an unprecedented level of outrage, often of the “faux” variety. Here, in chronological order, are the most controversial late-night clips of 2018.

John Oliver’s Trolls Mike Pence with Marlon Bundo Book

The day before Charlotte Pence released her children’s book about a “day in the life” of her father, Vice President Mike Pence, Last Week Tonight host John Oliver published his own, far more successful, parody version. As Oliver explained on his show in March, A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundotells the story of a gay bunny who wants to get married but is initially thwarted by an evil stink bug who bears a striking resemblance to the vice president. For her part, Charlotte Pence was surprisingly cool with the rival book, the proceeds from which went to support LGBTQ charities. “I mean, I think, you know, imitation is the most sincere form of flattery in a way,” she said on Fox Business Network. “But also, in all seriousness, his book is contributing to charities that I think we can all get behind. We have two books giving to charities that are about bunnies so I’m all for it really.”

More here.

When the news broke that

When the news broke that  On Friday afternoon, a text arrived from Israel letting me know of

On Friday afternoon, a text arrived from Israel letting me know of  Is Allah, the God of Muslims, a different deity from the one worshiped by Jews and Christians? Is he even perhaps a strange “moon god,” a relic from Arab paganism, as some anti-Islamic polemicists have argued? What about Allah’s apostle, Muhammad? Was he a militant prophet who imposed his new religion by the sword, leaving a bellicose legacy that still drives today’s Muslim terrorists? Two new books may help answer such questions, and also give a deeper understanding of Islam’s theology and history.

Is Allah, the God of Muslims, a different deity from the one worshiped by Jews and Christians? Is he even perhaps a strange “moon god,” a relic from Arab paganism, as some anti-Islamic polemicists have argued? What about Allah’s apostle, Muhammad? Was he a militant prophet who imposed his new religion by the sword, leaving a bellicose legacy that still drives today’s Muslim terrorists? Two new books may help answer such questions, and also give a deeper understanding of Islam’s theology and history. In his classic 1923 essay, “

In his classic 1923 essay, “ Every time we look at a face, we take in a flood of information effortlessly: age, gender, race, expression, the direction of our subject’s gaze, perhaps even their mood. Faces draw us in and help us navigate relationships and the world around us.

Every time we look at a face, we take in a flood of information effortlessly: age, gender, race, expression, the direction of our subject’s gaze, perhaps even their mood. Faces draw us in and help us navigate relationships and the world around us. Hugh Ryan in The Boston Review:

Hugh Ryan in The Boston Review: James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books:

James McAuley and Greil Marcus, and a reply by Mark Lilla in the New York Review of Books: WHEN

WHEN Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg.

Just a few years ago Yuval Noah Harari was an obscure Israeli historian with a knack for playing with big ideas. Then he wrote Sapiens, a sweeping, cross-disciplinary account of human history that landed on the bestseller list and remains there four years later. Like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens proposed a dazzling historical synthesis, and Harari’s own quirky pronouncements—“modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history”— made for compulsive reading. The book also won him a slew of high-profile admirers, including Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg. But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous

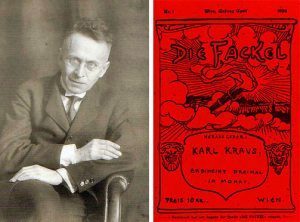

But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous  Vienna as a bourgeois, democratic city was never a stable entity. The liberal bourgeoisie came to municipal power in Vienna in the 1860s, yet the authority of the monarchy and aristocracy persisted, though in a weakened form, and, unlike the partial integration of the bourgeoisie into the social world of the British and French aristocracy, it kept its doors barred to the newcomers. And almost as soon as the liberals gained a foothold, a third element asserted itself, a gathering din of nationalist agitations from the patchwork of ethnicities that constituted the Habsburg Empire, each growing restless in the dilapidating imperium. The Liberals, never fully in control, saw their influence hedged and threatened almost immediately.

Vienna as a bourgeois, democratic city was never a stable entity. The liberal bourgeoisie came to municipal power in Vienna in the 1860s, yet the authority of the monarchy and aristocracy persisted, though in a weakened form, and, unlike the partial integration of the bourgeoisie into the social world of the British and French aristocracy, it kept its doors barred to the newcomers. And almost as soon as the liberals gained a foothold, a third element asserted itself, a gathering din of nationalist agitations from the patchwork of ethnicities that constituted the Habsburg Empire, each growing restless in the dilapidating imperium. The Liberals, never fully in control, saw their influence hedged and threatened almost immediately. Anglo-Saxon London suffers from an image problem, or more precisely from the problem that we have no image of it at all. In contrast to the showy glamour of Roman Britain, with its amphitheatres, temples and abundance of literature, or the vibrant cultural melting pot of the Tudor era, the Anglo-Saxon metropolis has almost no remaining visible architecture, a dearth of written sources and a patchy archaeological presence.

Anglo-Saxon London suffers from an image problem, or more precisely from the problem that we have no image of it at all. In contrast to the showy glamour of Roman Britain, with its amphitheatres, temples and abundance of literature, or the vibrant cultural melting pot of the Tudor era, the Anglo-Saxon metropolis has almost no remaining visible architecture, a dearth of written sources and a patchy archaeological presence. Steven Strogatz in the NYT:

Steven Strogatz in the NYT: