Daniel Mendelsohn in The New Yorker:

Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage—

Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage—

I recognize that he is that king of Rome,

Gray headed, gray bearded, who will formulate

The laws for the early city . . .

—he was confident that he’d succeed. His name was Hadrian.

Through the centuries, others sought to discover their fates in this book, from the French novelist Rabelais, in the early sixteenth century (some of whose characters play the game, too), to the British king Charles I, who, during the Civil War—which culminated in the loss of his kingdom and his head—visited an Oxford library and was alarmed to find that he’d placed his finger on a passage that concluded, “But let him die before his time, and lie / Somewhere unburied on a lonely beach.” Two and a half centuries later, as the Germans marched toward Paris at the beginning of the First World War, a classicist named David Ansell Slater, who had once viewed the very volume that Charles had consulted, found himself scouring the same text, hoping for a portent of good news.

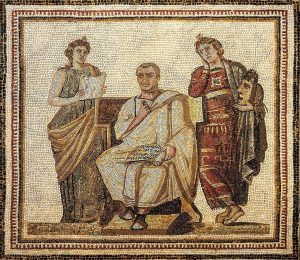

What was the book, and why was it taken so seriously? The answer lies in the name of the game: sortes vergilianae. The Latin noun sortes means lots—as in “drawing lots,” a reference to the game’s element of chance. The adjective vergilianae, which means “having to do with Vergilius,” identifies the book: the works of the Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro, whom we know as Virgil. For a long stretch of Western history, few people would have found it odd to ascribe prophetic power to this collection of Latin verse. Its author, after all, was the greatest and the most influential of all Roman poets. A friend and confidant of Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, Virgil was already considered a classic in his own lifetime: revered, quoted, imitated, and occasionally parodied by other writers, taught in schools, and devoured by the general public. Later generations of Romans considered his works a font of human knowledge, from rhetoric to ethics to agriculture; by the Middle Ages, the poet had come to be regarded as a wizard whose powers included the ability to control Vesuvius’s eruptions and to cure blindness in sheep.

However fantastical the proportions to which this reverence grew, it was grounded in a very real achievement represented by one poem in particular: the Aeneid, a heroic epic in twelve chapters (or “books”) about the mythic founding of Rome, which some ancient sources say Augustus commissioned and which was, arguably, the single most influential literary work of European civilization for the better part of two millennia.

More here.

Two Southern belles on the run get catcalled one too many times by the same schlubby dude; they blow up his truck. A couple of rough-and-ready French chicks talk their way into an architect’s house—his place is “like a drawing by a well-balanced child,” as is his smug, suave, symmetrical mug—and point their Smith & Wessons at him, all the while admiring both his book collection and his calm under pressure. “It’s clear to me,” one of them tells him affectionately, “that you stand out from our past encounters.” Then she shoots him in the face. “Get your fucking hands off me, goddamn it!” yells a leader of the National Women’s Political Caucus at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, addressing the member of the white-guy network-news crowd who is trying to restrain her as she rages over their failure to cover her group’s contributions. “The next son of a bitch that touches a woman is gonna get kicked in the balls.” A ten-year-old African American girl, menaced by a white boy, picks up a chunk of brick and aims it at him. When an avowed pussy-grabber tries to win a presidential debate against his female opponent by trotting out a bunch of women who’ve accused her husband of rape and other misconduct, a woman journalist takes to cable news to defend her beloved historic candidate, “shaking and red-faced with rage.”

Two Southern belles on the run get catcalled one too many times by the same schlubby dude; they blow up his truck. A couple of rough-and-ready French chicks talk their way into an architect’s house—his place is “like a drawing by a well-balanced child,” as is his smug, suave, symmetrical mug—and point their Smith & Wessons at him, all the while admiring both his book collection and his calm under pressure. “It’s clear to me,” one of them tells him affectionately, “that you stand out from our past encounters.” Then she shoots him in the face. “Get your fucking hands off me, goddamn it!” yells a leader of the National Women’s Political Caucus at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, addressing the member of the white-guy network-news crowd who is trying to restrain her as she rages over their failure to cover her group’s contributions. “The next son of a bitch that touches a woman is gonna get kicked in the balls.” A ten-year-old African American girl, menaced by a white boy, picks up a chunk of brick and aims it at him. When an avowed pussy-grabber tries to win a presidential debate against his female opponent by trotting out a bunch of women who’ve accused her husband of rape and other misconduct, a woman journalist takes to cable news to defend her beloved historic candidate, “shaking and red-faced with rage.” Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage—

Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the throne; after opening the book to this passage— In February of

In February of Brains are important things; they’re where thinking happens. Or are they? The theory of “

Brains are important things; they’re where thinking happens. Or are they? The theory of “ Admiring the great thinkers of the past has become morally hazardous. Praise Immanuel Kant, and you might be reminded that he believed that ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites,’ and ‘the yellow Indians do have a meagre talent’. Laud Aristotle, and you’ll have to explain how a genuine sage could have thought that ‘the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject’.

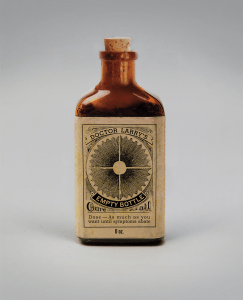

Admiring the great thinkers of the past has become morally hazardous. Praise Immanuel Kant, and you might be reminded that he believed that ‘Humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites,’ and ‘the yellow Indians do have a meagre talent’. Laud Aristotle, and you’ll have to explain how a genuine sage could have thought that ‘the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject’. Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t.

Give people a sugar pill, they have shown, and those patients — especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence — will improve. Tell someone a normal milkshake is a diet beverage, and his gut will respond as if the drink were low fat. Take athletes to the top of the Alps, put them on exercise machines and hook them to an oxygen tank, and they will perform better than when they are breathing room air — even if room air is all that’s in the tank. Wake a patient from surgery and tell him you’ve done an arthroscopic repair, and his knee gets better even if all you did was knock him out and put a couple of incisions in his skin. Give a drug a fancy name, and it works better than if you don’t. Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven?

Deborah Chasman: The book focuses on the 2016 election and what made the public sphere so vulnerable to what you call “disinformation, propaganda, and just sheer bullshit.” You resist the idea that technology was the primary driver of that problem, that the manipulation of Facebook’s platform, the Russian intervention, and fake news led to a Trump victory. What did you find in your research that led you to challenge the now common story that extreme polarization has been technologically driven? The main attraction in the

The main attraction in the  François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

François-Marie d’Arouet was the kind of precocious teen who always got invited to the best parties. Earning a reputation for his wit and catchy verses among the elites of 18th-century Paris, the young writer got himself exiled to the countryside in May 1716 for writing criticism of the ruling family. But Arouet—who would soon adopt the pen name “Voltaire”—was only getting started in his takedowns of those in power. In the coming years, those actions would have far more drastic repercussions: imprisonment for him, and a revolution for his country. And it all started with a story of incest. In 1715, the young Arouet began a daunting new project: adapting the story of Oedipus for a contemporary French audience. The ancient Greek tale chronicles the downfall of Oedipus, who fulfilled a prophecy that he would kill his father, the king of Thebes, and marry his mother. Greek playwright Sophocles wrote the earliest version of the play in his tragedy, Oedipus Rex. As recently as 1659, the famed French dramatist Pierre Corneille had adapted the play, but Arouet thought the story deserved an update, and he happened to be living at the perfect time to give it one.

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’

The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’ The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

The book was supposed to end with the inauguration of Barack Obama. That was Jill Lepore’s plan when she began work in 2015 on her new history of America, These Truths (W.W. Norton). She had arrived at the Civil War when Donald J. Trump was elected. Not to alter the ending, she has said, would have felt like “a dereliction of duty as a historian.”

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s

Europe’s outlook can appear bleak these days: the Brexit downward spiral continues, both Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel are weakened, and Italy’s  I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior.

I think much of my body awareness, in addition to my literary awareness, comes from Joan Didion. In Play It As It Lays, her 1970 novel (less popular than Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but still beloved), bodies are unpredictable geodes. Protagonist Maria’s (Mar-eye-ah’s) insides are vibrant with colour and edges and productive capability, but also completely invisible. She mines for menstruation in there, hoping she isn’t pregnant, which of course she is. A doctor ‘scrapes’ her zygote (a geological-seeming name in itself) out in an abortion scene that is refreshingly without either cynicism or romanticised maternal strickenness. But it doesn’t particularly matter (at least superficially) what goes on in there, in the novel’s bright and weird physical and psychological interiors. Didion is more interested in the woman’s outside, and what it can control. Maria has dreams that a “shadowy Syndicate” occupy her home in an illicit disposal operation. The grey flesh of victims clogs sinks, and water in drains begins to rise. So, certainly, a fear of the watery interior banishes Maria from her home into a tiny apartment, and structures several chapters of the novel. But my impression is that, despite being a clear-eyed writer of insides (especially those of women like herself) and a notable mid-century explorer of what Maggie Nelson has called “a situation of meat”, the disturbing softness and fallibility of the body and of consciousness, Didion is more interested in the hard geological outside, and whether it is hard, and how hard it is. What is women’s hardness? In the end, Maria—whose character is a variation on and also a criticism of the ‘madwoman in the attic’ trope—smokes half a joint, accrues a new psychosis or fixation, and moves back into that fleshy house with a life of its own, braving the interior. Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic.

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, the work of James Baldwin began to enjoy a renaissance that was both much overdue and comfortless. Baldwin stands as one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century, and any celebration of his work is more than welcome. But it was less a reveling than a panic. The eight years of the first black president were giving way to some of the most blatant and vitriolic displays of racism in decades, while the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others too numerous to list sparked a movement in defense of black lives. In Baldwin, people found a voice from the past so relevant that he seemed prophetic. In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for.

In our house, it has always been the most dreaded part of Thanksgiving. More painful than hand-scrubbing the casserole pan. More excruciating than listening to our libertarian cousin. I speak of the custom of forced gratitude — of going around the table and telling everyone what we’re thankful for.