Month: November 2017

Cryptos Fear Credit

Perry G. Mehrling over at his website:

One of the most fascinating things about the technologist view of the world is their deep suspicion (even fear) of credit of any kind. They appreciate all too well the extent to which modern society is constructed as a web of interconnected and overlapping promises to pay, and they don’t like it one bit. (One of my interests these days is “Financialization and its Discontents”, and I dare say that the discontent of the technologists is as deep as that of the most committed Polanyian, but of a completely opposite sort.) Fiat money is untrustworthy enough, promises to pay fiat money are doubly untrustworthy. One way around the problem would be to require full collateralization of all such promises, maybe even using so-called “smart contract” technology to ensure that promised payments are made automatically, basically an equity-based rather than debt-based system. In effect, we have here a version of Henry Simons’ Good Financial Society, but with peer-to-peer cryptocurrency taking the place of his 100% reserve money. Simons was of course responding to the global credit collapse of the Great Depression; the cryptos are responding instead to the more recent global financial crisis.

I view all of this through the lens of the money view, which places banking at the center of attention, views banking as fundamentally a swap of IOUs, and views money as nothing more than the highest form of credit. It is view developed not so much around a philosophical ideal but rather as a way of making sense of the operation of the world as it actually exists, outside the window as it were. In that world, the payment system is essentially a credit system, in which offsetting promises to pay clear with only very minimal use of money. And prices arise from the activity of profit-seeking dealers who absorb fluctuations in demand and supply by standing ready to take any excess onto their own balance sheet, relying on credit markets to fund the resulting inventory fluctuations. One can imagine automating a lot of that activity–and blockchain technology may well be useful for that task–but one cannot imagine eliminating the credit element. Credit is not a bug, but a feature.

More here.

All of the World’s Money and Markets in One Visualization

Via Lawrence Wilkinson over at (Roughly) Daily, and infographic over at Visual Capitalist [h/t: Sean Hinton]:

More here.

America’s Political Economy: Lost Generations–Cumulative Impact of Mass Incarceration

Adam Tooze over at his website:

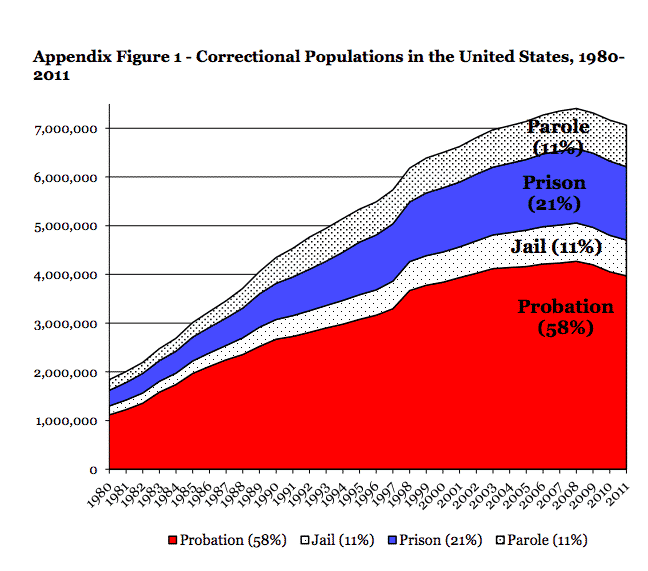

In the 1970s America embarked on a ghastly experiment in mass incarceration. This is part of a wider process of criminalization, driven by shifting race relations, the “War on drugs” and local law enforcement politics. It is anomalous in international comparison and its impact is clearly ruinous. Living in any American community you feel its impact all around you. But how big is it footprint? How can it be quantified?

One index is the scale of the prison and jail population at any moment in time. It soared from c. 400,000 the mid 1970s to 2.3 million in 2010. This is appalling but it understates the impact of criminalization because it does not count those who have been convicted of felonies and not incarcerated. Furthermore, it counts only those currently detained, rather than the entire population of people, mainly men, who have been processed by the system and bear its stigma for the rest of their lives.

Calculating the size of those wider populations requires one to consult a wider array of data not only on the prison and jail populations, but also those on parole and those convicted of felonies as a whole. It also requires us to move from the flow of people processed by the system in any given period to the stock of those who have been affected by it over a period of decades.

Source: http://users.soc.umn.edu/~uggen/former_felons_2016.pdf

To calculate the entire population touched by the system one has to make certain demographic assumptions about the rate at which ex-prisoners and felons die as well as their recidivism rates (to avoid those who have been convicted, imprisoned, released and then reconvicted and reincarcerated being counted many times over).

More here.

Safe and speedy: what’s not to love about e-bikes?

Leo Mirani in The Economist:

If there is one thing I learnt in my week of riding an electric bike, it is that the cycling public of London puts people who use the assistance of a motor on roughly the same moral plane as the Daily Mail puts immigrants. They are probably the sort of people who double-dip their chips and disrespect queuing. In short, they are cheating. Were cycling a sport, with rules dictating that a rider may only use her own energy, then, yes, it would be cheating. But for those of us not competing in the Tour de France, for those of us simply looking for a way to get around town safely, comfortably and quickly, using an electric bike is not cheating any more than using an electric kettle. And unlike double-dipping or queue-jumping, e-biking has no societal cost – if anything, it carries benefits. Let’s start with the most important consideration: safety. In a previous piece for 1843, I complained that a small minority of London’s cyclists can be aggressive and impolite on the road (to which that small minority responded by being aggressive and impolite to me on Twitter). One reason is that they are poorly served by London’s still developing cycling infrastructure. Sometimes breaking the rules is the only way to stay alive. Another reason for their blasé approach to traffic regulations is that setting off from a standing start is the most energy-intensive aspect of cycling. That is why some are loath to stop for red lights or at pedestrian crossings.

E-bikes remove the second reason entirely and ameliorate concerns about the first. A common misconception is that an e-bike requires no effort – that they are simply cut-rate mopeds. On the contrary, most e-bikes only supply motor assistance when the pedals are pushed. Depending on the cycle and the power setting, a rider can get between anywhere from one-and-a-half to three times as much energy out of the thing as she puts in. That means setting off becomes near effortless, making cyclists more likely to stop when they should. Moreover, the assistance helps cyclists rapidly accelerate out of danger if they find themselves in a sticky situation. And just in case they get carried away, British law requires all e-bikes sold here to cut out motor assistance at 15mph, or 24kmph, in line with other European countries. (North America has a more generous 20mph limit.)

More here.

Is it too late to save the world?

Jonathan Franzen in The Guardian:

If an essay is something essayed – something hazarded, not definitive, not authoritative; something ventured on the basis of the author’s personal experience and subjectivity – we might seem to be living in an essayistic golden age. Which party you went to on Friday night, how you were treated by a flight attendant, what your take on the political outrage of the day is: the presumption of social media is that even the tiniest subjective micronarrative is worthy not only of private notation, as in a diary, but of sharing with other people. The US president now operates on this presumption. Traditionally hard news reporting, in places like the New York Times, has softened up to allow the I, with its voice and opinions and impressions, to take the front-page spotlight, and book reviewers feel less and less constrained to discuss books with any kind of objectivity. It didn’t use to matter if Raskolnikov and Lily Bart were likable, but the question of “likability,” with its implicit privileging of the reviewer’s personal feelings, is now a key element of critical judgment. Literary fiction itself is looking more and more like essay.

Some of the most influential novels of recent years, by Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgaard, take the method of self-conscious first-person testimony to a new level. Their more extreme admirers will tell you that imagination and invention are outmoded contrivances; that to inhabit the subjectivity of a character unlike the author is an act of appropriation, even colonialism; that the only authentic and politically defensible mode of narrative is autobiography. Meanwhile the personal essay itself – the formal apparatus of honest self-examination and sustained engagement with ideas, as developed by Montaigne and advanced by Emerson and Woolf and Baldwin – is in eclipse. Most large-circulation American magazines have all but ceased to publish pure essays. The form persists mainly in smaller publications that collectively have fewer readers than Margaret Atwood has Twitter followers.

Should we be mourning the essay’s extinction? Or should we be celebrating its conquest of the larger culture?

More here.

The Art of Survival: On Santiago Zabala’s “Why Only Art Can Save Us”

Martin Woessner in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

MAURA AXELROD’S recent documentary film, Maurizio Cattelan: Be Right Back (2016), is a portrait of an elusive and controversial artist, one who has consistently turned manufactured scandals — a miniaturized sculpture of Hitler praying over here, an oversized middle finger in front of a stock exchange over there — into handsome paydays, whether in his native Italy, his adopted New York City, or many other places in between. Cattelan cuts a captivating figure on-screen: he is handsome, sly, seemingly in on the joke that is the global art market. It is easy to see why his works have been popular not just with curators and collectors, but also with museum-goers. Cattelan talks openly about his art, without a whole lot of pretense and without relying on academic jargon, either. How refreshing — he’d be perfect for the Guggenheim!

Only halfway through Axelrod’s film does the unsuspecting viewer begin to have doubts. Doesn’t the talking head on-screen seem a little young to have produced all these works, to have staged all these exhibitions? Don’t his words seem, well, a little rehearsed? The illusion is eventually revealed. It turns out Cattelan has been utilizing a surrogate for years, a stand-in who makes public appearances and sits for interviews in his stead. Naturally, the documentary would be no different. Suddenly, everything about Maurizio Cattelan: Be Right Back seems artificial, constructed. The artist has left the building. Maybe he was never even in it in the first place.

This trick has been pulled before (the 2010 Banksy film Exit Through the Gift Shop is an immediate and recognizable precursor). Still, it says something meaningful not just about our ambivalent relation to contemporary art but also about our complicated relation to truth and reality these days. If everyone agrees that the international art market is a fiction, a confidence game of global proportions, what else can artists do but find new things to fictionalize, including, perhaps most of all, themselves? Similarly, if everyone agrees that politics is, above all else, a performance, why should it come as a surprise that we continue to elect actors — “reality television” actors, no less — to high offices?

There is a growing consensus today about the dangers of living in a post-truth era, about the need for a new realism, which might cut through all of the artifice — all of the nonsense — and set things straight. The philosopher Santiago Zabala will have none of it. In his new book, Why Only Art Can Save Us: Aesthetics and the Absence of Emergency, Zabala rejects this rappel à l’ordre and suggests that now is precisely not the time to banish the poets from the city. It is from the artists, not the philosopher-kings, he thinks, that we have the most to learn.

More here.

Why Don’t Philosophers Talk About Slavery?

Chris Meyns in The Philosophers' Magazine:

No one is obliged to study any particular topic. But philosophers aren’t stupid. They’re trained to step back, reflect, and should notice when their passion-driven work morphs into a collective omission.

Perhaps there’s simply little to talk about. A lack of source materials. Did philosophers in early modern times even discuss enslavement?

They did. There are some big name philosophers we know and love. John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government (1690) insists that all “men” are naturally in “a state of perfect freedom … [and] equality”, and that no one could sell themselves into slavery for money, even if they wanted to. Some are quick to celebrate anti-slavery pamphlets, such as Montesquieu’s claim in 1748 that “The state of slavery is in its own nature bad”.

There are also less familiar names. Meet Phyllis Wheatley (1753–1784), one of the first African-American published authors, whose poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America” reflects her own experience. Meet Quobna Ottobah Cugoano (1757–ca. 1791), born in present-day Ghana. He survived abduction and forced labour exploitation at the sugar plantations of Grenada. His Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787) refutes point-by-point all attempts of “barbarous inhuman Europeans” to justify slavery. Cugoano argued for a global duty to liberate enslaved people: “Wherefore it is as much the duty of a man who is robbed in that manner to get out of the hands of his enslaver, as it is for any honest community of men to get out of the hands of rogues and villains.” Meet also Olaudah Equiano's (1746–1797), whose The Interesting Narrative and the Life of "Olaudah Equiano" or Gustavus Vassa, the African, published in 1789, presents a host of considerations about enslavement, dignity and empowerment. And meet Doctor of Philosophy, Anton Wilhelm Amo (1703–1759), originally from Axim (in today’s Ghana) and later associated with the German universities of Jena and Halle. Amo published against slavery, in addition to writing on philosophy of mind and philosophical method. Having experienced enslavement first-hand, these philosophers write from a position of epistemic authority.

There is also a ripple of white European women philosophers, who challenge their own subjugated position in society as one of enslavement. “If all men are born free, how is it that all women are born slaves?”, inquires Mary Astell in Some Reflections Upon Marriage (1706). Judith Drake, in An Essay in Defence of the Female Sex (1696), complains that: “Women, like our Negroes in our Western Plantations, are born Slaves, and live Prisoners all their Lives.” These white women appropriated images from African-Caribbean plantation enslavement to lament their own social condition.

More here.

On Both Page and Screen, Polish Master Stanislaw Lem Makes You Question Reality

Isaac Butler in The Village Voice:

Like a lot of kids, I was hipped to Stanislaw Lem, the Polish master of genre fiction, by a bespectacled, pony-tailed fellow-traveler amongst the self-segregated literary geeks who congregated at one end of my high school’s third floor. By then, I was already heavy into Neuromancer and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and Dune, but reading Stanislaw Lem for the first time was like discovering a secret treasure chest hoarding everything I loved. Here was where Terry Gilliam got the mixture of laughter and terror that makes Brazil so vital; here was Philip K. Dick’s paranoia stripped of its psychedelic wallpaper and painted over with a droll half-smile. Whether reading about The Cyberiad’s Trurl and Klapaucius, hapless robot inventors traveling the universe solving problems that they usually had caused in the first place, or Eden, in which a Star Trek–like interstellar mission discovers a planet with a domineering and invisible totalitarian government, each successive Lem work felt like it was expanding the idea of the possible.

Lem is probably best known in the United States for his novel Solaris, which inspired films of the same name by directors on the order of Andrei Tarkovsky and Steven Soderbergh. Had he only done that, dayenu, but Lem’s dozens of novels and short stories have proven massively influential — an influence that’s now on full view at “Stanisław Lem on Film,” a series of screen adaptations of the author’s work running through November 11 at Anthology.

Although known first and foremost as a science-fiction writer, Lem dabbled in a variety of modes: horror, detective procedurals, semi-autobiographical realism. But there are certain hallmarks that recur throughout his novels and the films inspired by them.

More here.

A lot of scientific discoveries in the 19th century made their way into 20th century textbooks — but have since been proven wrong

‘THE INVENTED PART’ BY RODRIGO FRESÁN

George Henson at The Quarterly Conversation:

Having read The Invented Part, it is not surprising that Fresán is often mentioned in the same breath as Bolaño and Cortázar; Bolaño because he is widely considered to be the Chilean’s heir, a folly that I will not elaborate on here, and because Fresán was also a close friend of his; and Cortázar because, as I stated above, The Invented Part is, rightly or wrongly, compared frequently to Cortázar’s magnum opus, Hopscotch; but more importantly because, like Bolaño’s and Cortázar’s translated works, The Invented Part is a welcome addition to the canon of translated Latin American literature.

Unlike Bolaño and Cortázar, however, the appearance of Fresán’s work in English has been belated and sparing. Of this ten books, only two have appeared in English: Kensington Gardens (Faber and Faber 2005), translated by Natasha Wimmer, and The Invented Part, translated skillfully by Will Vanderhyden and released in May of this year. Fortunately, Open Letter is scheduled to publish two other Fresán novels, The Bottom of the Sky (May 2018) and Mantra (TBD), “with plans to complete the Parts trilogy as well,” presumably—hopefully—in Vanderhyden’s translations.

Unfortunately, translators, perhaps out of professional courtesy, or the fear of being labeled the translation police, are hesitant to comment on fellow translators’ work. The task, then, inevitably falls to reviewers who, frankly, are unqualified to do so, and whose critiques inevitably make references to “fluency” and “invisibility” or recur to bromides like, “This translation reads as if it were written in English,” an observation that at best is a backhanded compliment.

more here.

A new biography charts the history of Rolling Stone

Jessica Hopper at Bookforum:

Sticky Fingers raises an overdue question: Is the era of devoting epic tomes to the exploits of mercurial pricks officially over? If so, Joe Hagan’s skilled filleting of Jann Wenner’s history as the publisher of Rolling Stone magazine is one hell of a coffin nail.

The book was born over lunch at an upstate New York eatery. Wenner, in his egotism, offered Hagan, then a journalist at New York magazine, unfettered access and deep cooperation (he asked to review only details of his sex life, which are nonetheless abundant), without requiring final approval, so sure was he that Hagan’s excavation would evince his greatness. As it turns out, Wenner is furious about Hagan’s final product. After reading a prepublication galley of Sticky Fingers, the New York Post reports, a furious Wenner kicked Hagan off the bill of a panel discussion they were supposed to co-headline. Wenner’s cocksure bargain didn’t go as he’d planned—instead of further enshrining the myth of “Mr. Rolling Stone,” Hagan rightsized his legacy entirely.

Hagan, quite clearly, is without an agenda, and Sticky Fingers is not posited as a takedown of “Mr. Rolling Stone.” Still, the tenor of the accounting of Wenner’s life after 1967, the year he founded the magazine, is inevitably shaped largely by the fact that everyone who has ever loved or liked him seemingly loathed him in equal measure (the holdouts being Tom Wolfe, Wenner’s son Gus, possibly Bette Midler). Many offer remembrances from the seat of betrayal, often one that’s been steeped in acid resentment for decades.

more here.

john updike, letter writer

John Keenan at The Guardian:

Postal workers in Beverly, Massachusetts, no doubt learned by heart the route from their depot to the home of author John Updike, on the area’s north shore. In his biography of the celebrated writer, Adam Begley tells us that Updike’s wife Martha warned that “if he had access to email, he would spend every waking hour responding to messages, so he steered clear, relying on the postal service and FedEx”.

Katie Roiphe wrote in The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End: “Updike’s correspondence is so charming and lively and wonderful that it evokes the man more powerfully than his published bits of autobiography. It may not be surprising that much of the work of friendship, for Updike, existed on the page.”

But while Updike corresponded with the likes of John Barth, Joyce Carol Oates and Ian McEwan, it was not only authorly names and close friends that received his letters: James Schiff, an associate professor of English at the University of Cincinnati, is working on a volume of Updike’s letters and has unearthed thousands of letters, postcards, and notes the author sent to complete strangers who wrote to him.

more here.

Keeping the Faith

Melvin Rogers in The Boston Review:

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s latest book, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, is his clearest expression yet of political fatalism—his “deeply held belief that white supremacy was so foundational to this country that it would not be defeated in my lifetime, my child's lifetime, or perhaps ever.” As in Coates’s Between the World and Me (2015), we again encounter white supremacy not as a political ideology, but as the defining feature of the U.S. polity—its essential nature. The book comprises previously published essays—one for each of the eight years Barack Obama held the presidency—prefaced by moving biographical and personal meditations that give each chapter philosophical weight. Taken together, it is about Obama and the United States—and it is about Coates. It charts the course of Coates’s career from a time when he could not make ends meet to his recent position of speaking for and to Americans about Black America. Obama’s presidency made this possible; it opened the door for a “crop of black writers and journalists who achieved prominence during his two terms.” This is also a book about shattering a great illusion—the idea that Obama’s presidency represented black power. “Obama, his family, and his administration were a walking advertisement for the ease with which black people could be fully integrated into the unthreatening mainstream of American culture, politics, and myth. And that was always the problem.”

For Coates, Obama represented a possibility that had always been denied, the idea that a black American could one day inhabit the highest office of the land. And if a black American could be president, couldn’t the United States be more than the explicit racism of its past and the institutional racism of its present? Coates himself was taken by this seductive idea, something he laments throughout the book. As he explains:

It is not so much that I logically reasoned out that Obama’s election would author a post-racist age. But it now seemed possible that white supremacy, the scourge of American history might well be banished in my lifetime. In those days I imagined racism as a tumor that could be isolated and removed from the body of America, not as a pervasive system both native and essential to that body.

Herein lies the explanation for why a man who curries favor with white supremacists assumed the presidency after Obama. Donald Trump’s ascendancy was a virulent reaction not only to Obama, but to the idea that his presidency signaled the country’s embrace of a multiracial polity.

More here.

Machines seem to be getting smarter and smarter and much better at human jobs, yet true AI is utterly implausible. Why?

Luciano Floridi in Aeon:

Suppose you enter a dark room in an unknown building. You might panic about monsters that could be lurking in the dark. Or you could just turn on the light, to avoid bumping into furniture. The dark room is the future of artificial intelligence (AI). Unfortunately, many people believe that, as we step into the room, we might run into some evil, ultra-intelligent machines. This is an old fear. It dates to the 1960s, when Irving John Good, a British mathematician who worked as a cryptologist at Bletchley Park with Alan Turing, made the following observation:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion’, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultra-intelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control. It is curious that this point is made so seldom outside of science fiction. It is sometimes worthwhile to take science fiction seriously.

Once ultraintelligent machines become a reality, they might not be docile at all but behave like Terminator: enslave humanity as a sub-species, ignore its rights, and pursue their own ends, regardless of the effects on human lives.

If this sounds incredible, you might wish to reconsider.

More here. [Thanks to Dan Dennett.]

CAN WE STILL RELY ON SCIENCE DONE BY SEXUAL HARASSERS?

Adam Rogers in Wired:

The scientific community has been contending with its own habitual harassers. (Amid the Weinstein scandal, the news section of the journal Science broke the story of field geologists in Antarctica alleging abuse by their boss. As the planetary scientist Carolyn Porco tweeted: Imagine the implications of an abuser and his target confined on a long-duration space mission.)

This isn’t like art. Science’s results and conclusions are nominally objective; failures in the humanity of the humans who found them aren’t supposed to have any bearing. Yet they do.

Nazi “research” turned out to be barely-disguised torture; it was easy to condemn the people who did it and consign to history the crappy outcomes they collected. The racist abuses of the Tuskegee experiments and consent problems with human radiation exposure experiments of the post-World War II era yielded data of questionable use, but led to reform, to rethinking the treatment of human scientific subjects.

But what about, for example, exoplanets? Geoff Marcy, a pre-eminent astronomer at UC Berkeley, pioneered techniques for finding planets outside Earth’s solar system. He also, it seems, sexually harassed students without repercussion for decades.

More here.

The cancer of Islamist extremism spreads around the world

Fareed Zakaria in the Washington Post:

This week’s tragic terrorist attack in New York was the kind of isolated incident by one troubled man that should not lead to generalizations. In the 16 years since 9/11, the city has proved astonishingly safe from jihadist groups and individuals. And yet, speaking about it to officials in this major global hub 10,000 miles away, the conclusions they reach are worrying. “The New York attack might be a way to remind us all that while ISIS is being defeated militarily, the ideological threat from radical Islam is spreading,” says Singaporean Home Minister K. Shanmugam. “The trend line is moving in the wrong direction.”

The military battle against Islamist extremist groups in places such as Syria and Afghanistan is a tough struggle, but it has always been one that favored the United States and its allies. After all, the combined military forces of some of the world’s most powerful governments are up against a tiny band of guerrillas. On the other hand, the ideological challenge from the Islamic State has proved far more intractable. The terrorist group and ones like it have been able to spread their ideas, recruit disaffected young men and women, and infiltrate countries across the globe. Western countries remain susceptible to the occasional lone wolf, but the new breeding grounds of radicalism are once-moderate Muslim societies in Central, South and Southeast Asia.

Consider Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, long seen as a moderate bulwark.

More here.

Thomas Meadowcroft: The News in Music

HOW LORD BYRON INVENTED THE WILD HORSE

Susanna Forrest at Literary Hub:

Mazeppa is one of Lord Byron’s later works, written just a few years before his death and shortly after he had fled England with scandal on his heels and debt dragging at his ankles. His wife had left him, taking their daughter with her. His lovers were numerous and garrulous. Rumor accused him both of homosexual affairs and of an incestuous passion for his half sister. Mazeppa—funnily enough—is about a delirious dash into exile, undertaken reluctantly but transforming its subject into a hero. Within three years of publication, Byron’s publisher John Murray had sold an impressive 7,400 copies.

Byron found his protagonist in Voltaire’s History of Charles XII, King of Sweden. The real historical Ivan Mazepa (Byron added the extra “p”) was a Cossack leader famous for defecting from Russia to Sweden before the 1709 Battle of Poltava. In Ukraine he is still a hero, in Russia, a villain. According to Voltaire, as a young man in the 1660s he served as a page at the court of King John II Casimir in Poland but was caught cuckolding a noble who had him stripped naked, tied to a “wild horse” and thus dispatched all the way back to his Ukrainian homeland. The tall tale of his amorous escapades can be traced back to the memoirs of a courtier called Pasek who held a long-standing grudge against Mazepa. In Pasek’s account, when Mazepa is caught by the irate husband he’s strapped not to the back of a wild horse but his own tame saddle horse, which promptly scarpers back to its home stable via bramble patches. Voltaire upgraded the story. Byron took it further.

more here.

Joseph Conrad in a Global World

John Gray at Literary Review:

Corresponding with Bertrand Russell in 1922, Joseph Conrad confessed: ‘I have never been able to find in any man’s book or any man’s talk anything … to stand up for a moment against my deep-seated sense of fatality governing this man-inhabited world.’ Conrad was responding to Russell’s book The Problem of China, published in the same year, in which Russell had pinned his hopes for China and the world on ‘international socialism’ – ‘the sort of thing to which I cannot attach any sort of definite meaning’, Conrad observed. International socialism, he continued, was ‘but a system, not very recondite and not very plausible … and I know you wouldn’t expect me to put faith in any system’.

Conrad was a sceptic who believed that the human world was fuelled by illusions. He felt strongly about a number of the political issues of his day, such as the threat posed to Europe by Russian autocracy, and was horrified by the rapacity he witnessed being inflicted on the local population when he travelled through the Belgian Congo in 1890. But nothing could have been further from his way of thinking than high-minded dreams of a world without tyranny or empire. In his view, no change in political systems could eradicate the universal human propensity for savagery. He was suspicious of all large schemes of improvement.

more here.