Pankaj Mishra in The New Yorker:

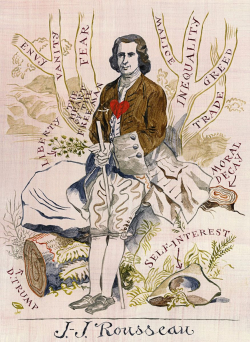

“I love the poorly educated,” Donald Trump said during a victory speech in February, and he has repeatedly taken aim at America’s élites and their “false song of globalism.” Voters in Britain, heeding Brexit campaigners’ calls to “take back control” of a country ostensibly threatened by uncontrolled immigration, “unelected élites,” and “experts,” have reversed fifty years of European integration. Other countries across Western Europe, as well as Israel, Russia, Poland, and Hungary, seethe with demagogic assertions of ethnic, religious, and national identity. In India, Hindu supremacists have adopted Rush Limbaugh’s favorite epithet “libtard” to channel righteous fury against liberal and secular élites. The great eighteenth-century venture of a universal civilization harmonized by rational self-interest, commerce, luxury, arts, and science—the Enlightenment forged by Voltaire, Montesquieu, Adam Smith, and others—seems to have reached a turbulent anticlimax in a worldwide revolt against cosmopolitan modernity. No Enlightenment thinker observing our current predicament from the afterlife would be able to say “I told you so” as confidently as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an awkward and prickly autodidact from Geneva, who was memorably described by Isaiah Berlin as the “greatest militant lowbrow in history.” In his major writings, beginning in the seventeen-fifties, Rousseau thrived on his loathing of metropolitan vanity, his distrust of technocrats and of international trade, and his advocacy of traditional mores. Voltaire, with whom Rousseau shared a long and violent animosity, caricatured him as a “tramp who would like to see the rich robbed by the poor, the better to establish the fraternal unity of man.” During the Cold War, critics such as Berlin and Jacob Talmon presented Rousseau as a prophet of totalitarianism. Now, as large middle classes in the West stagnate and billions elsewhere move out of poverty while harboring unrealizable dreams of prosperity, Rousseau’s obsession with the psychic consequences of inequality seems even more prophetic and disturbing.

“I love the poorly educated,” Donald Trump said during a victory speech in February, and he has repeatedly taken aim at America’s élites and their “false song of globalism.” Voters in Britain, heeding Brexit campaigners’ calls to “take back control” of a country ostensibly threatened by uncontrolled immigration, “unelected élites,” and “experts,” have reversed fifty years of European integration. Other countries across Western Europe, as well as Israel, Russia, Poland, and Hungary, seethe with demagogic assertions of ethnic, religious, and national identity. In India, Hindu supremacists have adopted Rush Limbaugh’s favorite epithet “libtard” to channel righteous fury against liberal and secular élites. The great eighteenth-century venture of a universal civilization harmonized by rational self-interest, commerce, luxury, arts, and science—the Enlightenment forged by Voltaire, Montesquieu, Adam Smith, and others—seems to have reached a turbulent anticlimax in a worldwide revolt against cosmopolitan modernity. No Enlightenment thinker observing our current predicament from the afterlife would be able to say “I told you so” as confidently as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an awkward and prickly autodidact from Geneva, who was memorably described by Isaiah Berlin as the “greatest militant lowbrow in history.” In his major writings, beginning in the seventeen-fifties, Rousseau thrived on his loathing of metropolitan vanity, his distrust of technocrats and of international trade, and his advocacy of traditional mores. Voltaire, with whom Rousseau shared a long and violent animosity, caricatured him as a “tramp who would like to see the rich robbed by the poor, the better to establish the fraternal unity of man.” During the Cold War, critics such as Berlin and Jacob Talmon presented Rousseau as a prophet of totalitarianism. Now, as large middle classes in the West stagnate and billions elsewhere move out of poverty while harboring unrealizable dreams of prosperity, Rousseau’s obsession with the psychic consequences of inequality seems even more prophetic and disturbing.

Rousseau described the quintessential inner experience of modernity: being an outsider. When he arrived in Paris, in the seventeen-forties, at the age of thirty, he was a deracinated looker-on, struggling with complex feelings of envy, fascination, revulsion, and rejection provoked by a self-absorbed élite. Mocked by his peers in France, he found keen readers across Europe. Young German provincials such as the philosophers Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Johann Gottfried von Herder—the fathers, respectively, of economic and cultural nationalism—simmered with resentment toward cosmopolitan universalists. Many small-town revolutionaries, beginning with Robespierre, have been inspired by Rousseau’s hope—outlined in his book “The Social Contract” (1762)—that a new political structure could cure the ills of an unequal and commercial society. In the past decade, a number of books have asserted Rousseau’s centrality and uniqueness. Leo Damrosch’s biography, “Restless Genius” (2005), identified Rousseau as “the most original genius of his age—so original that most people at the time could not begin to appreciate how powerful his thinking was.” Last year, István Hont, in “Politics in Commercial Society,” a comparative study of Rousseau and Adam Smith, argued that we have not moved much beyond Rousseau’s fears and concerns: that a society built around self-interested individuals will necessarily lack a common morality. Heinrich Meier, in his new book, “On the Happiness of the Philosophic Life” (Chicago), offers an overview of Rousseau’s thought through a reading of his last, unfinished book, “Reveries of a Solitary Walker,” which he began in 1776, two years before his death. In “Reveries,” Rousseau moved away from political prescriptions and cultivated his belief that “liberty is not inherent in any form of government, it is in the heart of the free man.”

More here.

About 2,000 miles east of Australia is collection of islands called New Caledonia. The French territory is astonishingly beautiful, but the most astonishing thing about it has got to be the crows. With their beguiling smarts, New Caledonian crows are the valedictorians of the avian world (which is saying a lot, since birds’ have neuron counts on par with apes). New Caledonians can solve certain logic puzzles as well as 7-year-olds do,construct their own tools, and they’ve sussed out that if you drop a stone into a glass of water, it will rise.