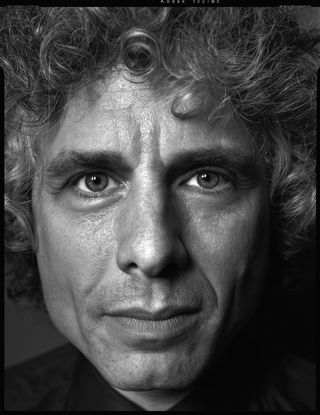

In TNR, Steven Pinker, on one side:

In his commentary on my essay “Science is Not your Enemy,” Leon Wieseltier writes, “It is not for science to say whether science belongs in morality and politics and art.” I reply: It is not for Leon Wieseltier to say where science belongs. Good ideas can come from any source, and they must be evaluated on their cogency, not on the occupational clique of the people who originated them.

Wieseltier’s insistence that science should stay inside a box he has built for it and leave the weighty questions to philosophy is based on a fallacy. Yes, certain propositions are empirical, others logical or conceptual or normative; they should not be confused. But propositions are not academic disciplines. Science is not a listing of empirical facts, nor has philosophy ever confined itself to the non-empirical.

Why should either discipline stay inside Wieseltier’s sterile rooms? Does morality have nothing to do with the facts of human well-being, or with the source of human moral intuitions? Does political theory have nothing to learn from a better understanding of people’s inclinations to cooperate, aggress, hoard, share, work, empathize, or submit to authority? Is art really independent of language, perception, memory, emotion? If not, and if scientists have made discoveries about these faculties which go beyond received wisdom, why isn’t it for them to say that these ideas belong in any sophisticated discussion of these topics?

And Leon Wieseltier on the other:

What Pinker cannot bring himself to accept is that his beloved sciences, even when they do shed some light on aspects of art and literature, may shed little light and—for the purpose of understanding meaning (Pinker’s scare quotes around “meaning” may indicate a scare)—unexciting or inconsequential light. I gave the examples of the chemical analysis of a Chardin painting and the linguistic analysis of a Baudelaire poem. Many other examples could be given. “The theory of parent-offspring conflict”—I hope the grants for that particular breakthrough were not too large—is quite superfluous for the explication of Turgenev or Gosse. Nothing in the physical world, in the world of the senses, in the world of experience, can be immune from or indifferent to the categories of the sciences; but there are contexts in which scientific analysis may be trivial. That is not to say that science is trivial, obviously. But the belief that science is supreme in all the contexts, or that it has the last word on all the contexts, or that all the contexts await the attentions of science to be properly understood—that is an idolatry of science, or scientism. Pinker is wrong: I am not censoring scientists. They can say anything they want. But everything they say may not be met with grateful jubilation. So let the scientists in—they are already swarming in—to the humanities, but not as saviors or as superiors. And those swaggering scientists about whose intentions Pinker wants humanists to “relax”: they had better prepare themselves for a mixed reception over here, because over here the gold they bring may be dross.

More here. (Also see Daniel Dennett's comments on the earlier round of Pinker v. Wieseltier over at Edge.)

Dear Reader,