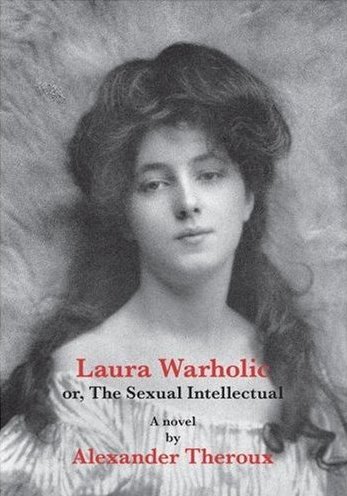

Alexander Theroux is the author of stories, poetry, essays, fables, critical studies and such novels as Three Wogs, Darconville's Cat, An Adultery and his latest, Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual, which came as Theroux's first novel in two decades. Rain Taxi calls the book “a massive, 878-page compendium of vituperation against contemporary society, jabs at pop culture, exposés of office politics, and exploration of life and love in modern times,” an encyclopedic novel that's “wandering, erudite, funny, opinionated, didactic, repetitive.” Colin Marshall originally conducted this conversation on the public radio program and podcast The Marketplace of Ideas. [MP3] [iTunes link]

About the new book: you can't really understand it unless you get to know the characters, and you get to know them very well through the course of the book. The protagonist, Eugene Eyestones — tell us a little bit about him.

About the new book: you can't really understand it unless you get to know the characters, and you get to know them very well through the course of the book. The protagonist, Eugene Eyestones — tell us a little bit about him.

I've always been interested in a person that was both idealistic and something of a failure. Vladimir Nabokov once pointed out that every character is a little ramification of the author, so I've distributed some of my hostilities and fascinations and occasional quirks to him. I wanted to have him as a kind of raisonneur and a satirical point of departure for the multifarious views on life that are presented in the book. He's the thread through the book, which is not to say that he's normal or well-balanced.

You say you give him a few qualities, a few opinions of your own. Which ones are the most prominent in him that you took for yourself?

It's really hard to say, because, as Goethe once said, all writing is confession. In away, I've distributed myself throughout the book in various characters. John Keats once pointed out that Shakespeare maybe had a very empty personality, he might have been a very bland person, because he gave away his personality, the various voices that he had, to different people as various as Prospero, Lady Macbeth, you name it. I can't really say there's a one-to-one correspondence to much in Eyestones. His rooms, in many ways, echo mine: I have a lot of books, I have a portrait of Dostoevsky, blah blah blah.

But I think I can be found in other characters with equal force. There's an occasional shotgun in the corner, metaphorically speaking. My toothbrush over there, a particular vase in the room, but I can't deny that I'm in other places as well. I distributed myself throughout, and probably have as bland a personality as Keats argued Shakespeare had — not to make any major analogies here, by the way.

You talk about Eyestones' idealism. He has a huge number of ideals, strongly held. What ideals of his really define him for you?

He has an elevated view of women, although a lot of people would argue, vociferously, the opposite direction. His expectations are high. The genre of this novel is a satire. Through dramatic irony, I try to present him as a corrective to the wayward world, the quark-reversal world, the nutty world, the excessive world, the secular world. His point of view I like to think is balanced, although, as I say, a lot of people wouldn't agree. Laura Warholic attacks him three-quarters of the way through the book for a lot of lunatic excesses she finds in him, but a lot of those excesses and ideals — let's take one to make this clear.

He's kind of disbelieving in the possibility of democracy. Indeed, he sees it as a leveling force. I spent quite a bit of time on an essay on democracy in this book, which aims in the direction of trying to talk about couples. There's a certain kind of democracy required of people involved in coupledom. You have to settle on man and woman — in these days, man and man, whatever — he's kind of doubtful about the possibility of that being successful. That would be one example. There are many I could go into, but that would be one.

Read more »

Although many consider football to be a global sport, a look at the history of the World Cup shows only a handful of nations have mastered it. FIFA – the game's world governing body – recognizes 208 national associations but just seven have celebrated having the best team on the planet.