In Part One of this article I wrote about the instability of the art-object. How its meaning moves, and inevitably cracks. In this follow-up I ponder text, the book, page and computer screen. Are they as stable as they appear? And how can we set them in motion?

Part Two

“There’s a way, it seems to me, that reality’s fractured right now, at least the reality that I live in. And the difficulty about… writing about that reality is that text is very linear and it’s very unified, and… I, anyway, am constantly on the lookout for ways to fracture the text that aren’t totally disorienting – I mean, you can take the lines and jumble them up and that’s nicely fractured, but nobody’s gonna read it.”

David Foster Wallace, PBS Interview, 1997

17th Century print technology was rubbish. Type could be badly set, ink could be over-applied, misapplied or just plain missed. Paper quality varied enormously according to local resources, the luck of the seasons or even the miserly want of the print maker out to fill his pockets. There are probably thousands of lost masterpieces that failed to make it through history simply because of the wandering daydreams of the printer's apprentice. But from error, from edit and mis-identification have come some of the clearest truths of the early print age. Truths bound not in the perfect grain or resolute words of the page, but in the abundance of poor materials, spelling mistakes and smudge. In research libraries across the globe experts live for the discovery of copy errors, comparing each rare edition side-by-side with its sisters and cousins in the vain hope that some random mutation has made it intact across the centuries.

17th Century print technology was rubbish. Type could be badly set, ink could be over-applied, misapplied or just plain missed. Paper quality varied enormously according to local resources, the luck of the seasons or even the miserly want of the print maker out to fill his pockets. There are probably thousands of lost masterpieces that failed to make it through history simply because of the wandering daydreams of the printer's apprentice. But from error, from edit and mis-identification have come some of the clearest truths of the early print age. Truths bound not in the perfect grain or resolute words of the page, but in the abundance of poor materials, spelling mistakes and smudge. In research libraries across the globe experts live for the discovery of copy errors, comparing each rare edition side-by-side with its sisters and cousins in the vain hope that some random mutation has made it intact across the centuries.

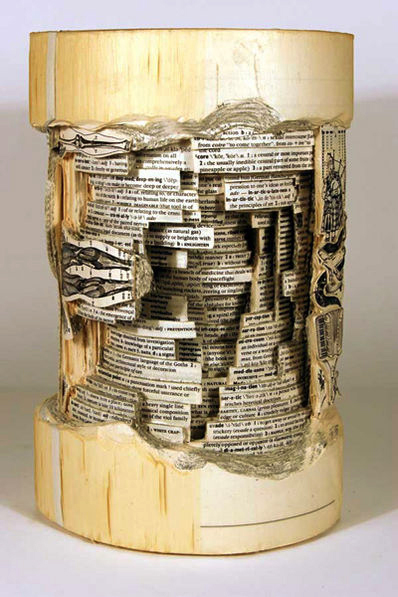

Since the invention of writing, and its evolutionary successor the printing-press, text has commanded an authority that far exceeds any other medium. By reducing the flowing staccato rhythms of speech to typographically identical indelible marks we managed, over the course of little more than 2000 years, to standardise the reading consciousness. But in our rush to commodify the textual experience we lost touch with the very material that allowed illiteracy to become the exception, rather than the rule. We forgot that it is the very fallibility of text and book that make them such powerful thinking technologies.

Read more »

Like Native Americans, European Jews and Rwandan Tutsis, Turkish Armenians seem to have been in the wrong place at the wrong time. “Children of Armenia,” Michael Bobelian's first book, describes the Ottoman Empire's 1915 mass extermination of this Christian minority without getting bogged down in “G-word” histrionics. “The purpose of this book is neither to prove the existence nor affirm the veracity of the Genocide,” Bobelian writes: The Armenian holocaust is a historical fact.