by Bill Murray

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Close cropped with a natty little mustache, Godfrey is kempt, forties, paunch-softened, with an easy smile. A veteran guide, he has been here before. Says it will take five hours to do the 250 kilometers to the crater and so it does.

No package tour jets preceded us when we flew into Kilimanjaro International Airport aboard a small plane from Nairobi, so the airport bank wasn’t open. Consequently, we have no Tanzanian Shillings.

Oxen pull plows across the fields. Buses are occasional and private cars are rarer than cows. At the time of this visit (several years ago), the road is primarily for foot traffic, human and animal. No matter how far from a village, people are everywhere walking on the roads, always. They only move to the verge, reluctantly, when a Land Rover thunders by.

The few vehicles you do pass are either chock full of ride-sharing local folks, or they’re hauling two or three white Europeans on safari, or maybe they’re jeeps that read something like, “Africa Wildlife Research Project, funded by Belgian government.”

What do you know, way out here Godfrey knows where to buy a few beers. Two hot Tuskers from Kenya, two hot Safari beers from Tanzania, a roadside bodega, no power, no refrigeration, just a handful of dusty beers on a shelf for four for five dollars at an anonymous shack, friendly enough, opaque to a stranger. Godfrey’s got this round.

•••••

The tectonic plates that mold and shape the earth are always moving, creating the great Himalayas, tearing apart the mid-Atlantic. Perhaps you have heard the general rule that the plates move at the speed your fingernails grow. That rule doesn’t hold everywhere.

While the Mid-Atlantic Ridge spreads 2.5 centimeters a year, the Great Rift Valley of Africa moves rather more slowly, around a millimeter. Even so there will come a day when the warm waters of the Indian Ocean will lap at, and then cover up, the cradle of human life, Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain.

For now though, and until it does, the Great Rift Valley is a singular tear in the earth, so long and life-giving that much of Africa’s history has occurred around it. So it is important to have some sense of this mighty 3,700-mile trench’s place in the world.

Its west and south are home to Africa’s Great Lakes, Lake Malawi between Mozambique, Malawi and Tanzania, Lake Tanganyika between Tanzania and Congo, Lake Kivu between Congo and Rwanda, Lakes Edward and Albert straddling Congo and Uganda, Uganda’s Lake George and Lake Victoria, on which Uganda’s capital Kampala and international airport at Entebbe lie, bordering Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda,

East and north, the newly forming Nubian and Somali tectonic plates separate along a line from south of Mt. Kilimanjaro all the way to the Red Sea. The rift continues under the sea into Jordan, crossing the Gulf of Aqaba and the Dead Sea, finally fading like an eclipse’s arc across Syria and Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

To a geologist, this rift system is one of the most electrifying places on the planet. Here is positively rhapsodic prose (for a geologist), from James Wood and Alex Guth in Africa’s Great Rift Valley: A Complex Rift System:

“basalt eruptions and active crevice formation have been observed in the Ethiopian Rift which permits us to directly observe the initial formation of ocean basins on land. This is one of the reasons why the East African Rift System is so interesting to scientists.”

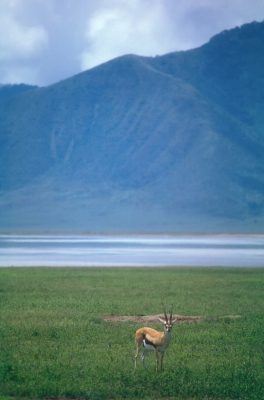

The Ngorongoro Crater, the remnants of a volcano probably larger than Kilimanjaro, was born of these basalt eruptions a couple or a few million years ago. At some point long ago, further rifting caused the abrupt withdrawal of lava from beneath the volcano, resulting in its collapse.

Ngorongoro is the largest unbroken and unflooded volcanic caldera in the world, 2000 feet from rim to floor and a hard to believe 192 miles in circumference. Marshland and acacia forests separated by plains and a lake support 30,000 or 40,000 animals most of the year inside the caldera. A drive around the rim is the distance from Boston to New York. Imagine.

•••••

Ramadan has just ended and there will be a huge Eid festival in Arusha. All 200,000 Arushans (back then), Muslim or not, will be in the streets. In preparation, the little stream that runs beside town has become an impromptu car wash around a car lot named Dimple Motors.

Ramadan has just ended and there will be a huge Eid festival in Arusha. All 200,000 Arushans (back then), Muslim or not, will be in the streets. In preparation, the little stream that runs beside town has become an impromptu car wash around a car lot named Dimple Motors.

Arusha looks like a friendly town, but driving through, it occurs to me that if you’d just dropped into Africa from Denver or Detroit or Duluth for the first time, the unfamiliarity might make you uncomfortable.

Do not fear. That will pass.

Before you know it you’ll relish the incongruous jumble of the African city. You’ll find yourself celebrating the difference from back home: A banner over the airport road marking independence (not that many years ago), sunshine filtered through dust thrown up by traffic on non-tarmacked roads, big welcoming smiles, bright sarongs and bare feet, baskets on girls’ heads, the scent of smoky-blue fires in pots on the roadside, shells of unfinished buildings stalled for reasons never to be known.

The waist-high trees of the Burka coffee estate stretch endless acre after acre, either side of the road. Impenetrable mist shrouds the steep eastern slope of Mt. Meru, off past the edge of town.

Shade trees line the far side of town before traffic finally eases. Open-backed, full-polluting Tata trucks fly by, public transport. People stand in the back, clutching at the cab. Ramshackle stalls: “Lucky Feed Mill.” “Lucky Family General Store.” “Moona Pharmacy.” “Beuty Saloon.” All the way west from Arusha, Masaai villages of seven or eight or a dozen mud-walled roundhouses with thatched round roofs.

Here is a toll plaza, deserted. Godfrey never slows down.

“We pay our tolls through gasoline taxes now.”

Why don’t they just fix the damned roads? A western conceit. If there were money to fix the roads they’d use it to do a dozen more important things first, better nutrition, child care, malaria eradication.

Termite mounds rise three feet from red clay-colored dirt. African roadways belong to the people, as the roads of American cities did before the coming of the car. People scramble and scoot as, hell bent to deliver us to the crater (after which he’ll be off work), Godfrey pounds along, 80 kilometers per hour when he can, ruts and puddles or not.

It’s a straight road for multiple kilometers until a fateful right turn and farewell to tarmac at a signpost, “Ngorongoro 101 km” onto a road that promises a low-grade brain-jostling headache for days.

•••••

This was once an outpost of Deutschland. Germany came late to the Scramble for Africa and left early when it was stripped of its colonies after World War One. Its important colonies were only four – today’s Togo, Cameroon and Namibia along the west coast and German East Africa, comprising today’s mainland Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda.

Chancellor Bismarck felt more pressing Realpolitikal concerns back home in Europe: “Here is Russian and here is France,” he said, “with Germany in the middle. That is my map of Africa.” Yet by 1884 as Britain and France madly staked their African claims, a sense Germans called Torschlusspanik, “door-closing-panic,” took hold, a fear that it might be left out. Traders felt mercantile pressure from their British and French rivals and let the government know it.

On his rise to power Bismarck declared that “the only healthy basis of a large state which differentiates it essentially from a petty state, is state egoism and not romanticism.” More than a decade later he reexamined his Africa policy, applied a healthy dose of large state egoism and with the support of the business communities in Hamburg and Bremen, Bismarck instructed the German explorer Dr Gustav Nachtigal to seize Cameroon, Togoland and Southwest Africa, now Namibia.

In early days, claiming swathes of territory merely meant visiting coastal clans and scooping up treaties at the point of superior European guns. Dr. Nachtigal claimed Togoland and Cameroon in July 1884. The captain of the German gunboat Wolf claimed Southwest Africa by the end of August, and they were off.

Meanwhile in the east a German explorer named Carl Peters leased the coastal holdings of the Sultan of Zanzibar. He made deals with local leaders for land to the north and south of British East Africa. Peters learned that King Mwanga of Buganda was shopping for an ally to help him reclaim his throne, offering treaties first come first served, and rushed to beat the British to a deal. He schemed to join German interior holdings with the coast to thwart the Brits, who in turn strove to tie British East Africa to their territory of Sudan to the north.

Carl Peters’s frenzied bit of the Scramble came to naught over European politics, for as Britain dreamed of the bits of east Africa that Peters had cobbled together, Bismarck coveted Heligoland, an island the Brits held just 25 miles off the German coast, as a Baltic naval base.

Germany got its island, Britain its colonies and so came a general settling of borders, enabling the British to build a railway from Mombasa on the coast to Lake Victoria (the ill-starred Lunatic Express). Germany would control land to the south, German East Africa, now Tanzania, home of Ngorongoro Crater.

There is hardly a trace of the German language in East Africa today. English, on the other hand, is widely spoken in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. It is overlaid on Kiswahili, a Bantu language that is either the indigenous, official or trade language of countries across east Africa, not only in Tanzania and Kenya but also in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Congo, the north of Mozambique and Zambia.

The word Swahili itself derives from Arabic for ‘the coast,’ underlining the ancient connection between the east African Bantus and traders from the Arab peninsula and Persia, who for centuries sailed their dhows up and down the shores of east Africa. Swahili terms for numbers, times of day, for please and friend and travel and danger and many more, borrow from Arabic. Along with vocabulary from Arabia and Persia, some east Africans also got religion. Perhaps a third of Tanzanians practice Islam today.

•••••

In Welsh legend, a shepherd named Guto Nyth Bran ran so fast that he could blow out a candle and be tucked into bed before the light faded. He must have practiced on the equator. The equator produces the fastest sunrises and sunsets on the planet, since the sun’s apparent movement is vertical. As the sun sets, and just as it sets, colors fade like flipping a switch. The road crawls around the edge of the escarpment and Lake Manyara spreads before us outside the crater in black and white. In a minute it has disappeared into the dark. Then, over the north side of the hill, we bear down in a dive for the crater rim. All of the lodges sit along the rim – none on the floor.

Traveling counter-clockwise along the rim, my wife Mirja bolts upright. In the Land Rover’s headlights, she has spotted a leopard! Lying right in the road! It is gone in a flash. Stealthy and rare as they are, this is an auspicious start indeed.

•••••

END PART ONE.